|

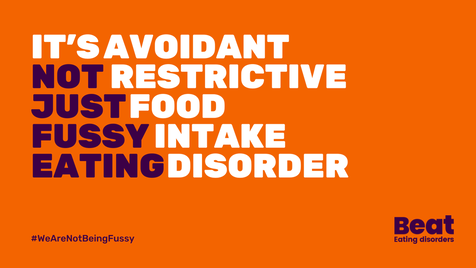

It's Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2024, and BEAT's theme is ARFID (Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder), which is what I'm going to attempt to write about today. I'm going to caveat this with I'm not an expert, but I don't think many people are given that there’s very little research, literature or training on ARFID. What there is tends to be about children and young people, mainly from a White Western perspective. So I'm writing this based on having worked with some people with ARFID (adults only) in my counselling practice, and from my own experiences. It’s important to note, that for people who do not have a diagnosis of ARFID (or any other eating disorder), your struggle is still absolutely valid and you are still worthy of help and support. What is ARFID? ARFID - Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder – is a lesser-known eating disorder, categorized in the 5th edition of the DSM-5 (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). ARFID is described as an “eating or feeding disturbance” which may include sensory sensitivity, fear of aversive consequences of eating, or lack of interest in eating. This can manifest in various ways, such as avoiding certain food textures, colours, or smells, experiencing a lack of appetite, or having a limited range of acceptable or safe foods. My personal experiences I describe my own experiences usually as "disordered eating" as I've fleeted around different difficulties in my life but never been diagnosed with an eating disorder. I never considered there was even an issue, until I started learning more about eating disorders, and learnt about the influence of diet culture and weight stigma in my life. When I learnt about ARFID, I could definitely relate with some of my experiences of being fearful of foods. I was fortunate enough to travel quite a long time in my 20’s, but was not so great on my guts. I had food poisoning numerous times and became anxious about what I could eat as almost everything seemed to make me feel nauseous, bloated and have a bad stomach. I saw various professionals - medical and holistic - many of whom seemed to want to tell me what not to eat. I did various elimination diets and nothing worked. I just got gradually more scared of what to eat. I even cut out tomatoes for a while, which for an avid pasta and pizza eater was really no good! My poor stomach has taken the brunt of most things in my life, emotionally and physically, which I manage on an ongoing basis still though it is much better now. It took me many years to start building up what I could eat again. It didn’t start with challenging myself to eat more foods, it started with finding more routine and stability when I moved back to the UK. I started having counselling, doing yoga and building up my relationship with myself, and food. I also had a lot of diet culture stuff I was trying to unpack, which was an added complexity. I didn't hate my body anymore but I certainly didn't love it. I was starting to be a little kinder to it at least. I felt brave enough gradually to try new things, but it’s scary when you’ve had bad experiences with food and it’s made you ill. I wanted to have variation in my eating and to reduce worrying about food, and some of that meant challenging diet culture narratives I’d picked up growing up, and societal ideas about “healthy” eating. I aimed for more of an intuitive eating approach and tried to get more in touch with my body, hunger signals and focus on what my body needs and how it felt instead of external influences. Like many people who have struggled with eating, I have foods and places I feel safer with, and I like to know what’s on the menu at places I eat beforehand. “Recovery” means different things to different people, there is no one-size-fits-all because everyone’s experiences are so nuanced and complex, but sometimes it just means managing a little better. Norms and expectations I feel way more at ease with food now, but I will never forget what the fear of eating feels like. I know what it's like to feel anxious about eating out, and eating at other people's houses. To be scared that there won't be anything for you to eat, and that people will judge you for being picky or difficult. To feel like you can’t eat like a normal person. It can be incredibly shaming to feel like the odd one out, that you're being too dramatic, and is easy to blame yourself for these things. This has a huge impact on your life; socially, at work, career choices etc. It can really hold you back. As a counsellor now working with eating disorders and disordered eating, I feel my lived experiences are important and beneficial in this work. Some people with eating difficulties will have experienced things very differently, but I still have some insight and I understand the turmoil, frustration, shame and various other underlying feelings associated with eating disorders. The main thing I’d like to let people know is that your struggle is valid, it’s a tough way to live, it is definitely not your fault and you absolutely do deserve help and support.

Normal eating? So what even is normal eating anyway and who makes the rules? Spoiler… “normal” eating doesn’t exist. Diet culture has a lot to answer for, but we also start learning about food from the moment we're born. Early childhood experiences and narratives around food can create templates which run through your whole life. We learn how to eat from others, which is heavily influenced by culture and society and “norms” can become ingrained. Some people, like myself, will learn that there are “good and bad foods” and that healthy equals being thin and fat is bad. As babies we cry and get fed, but then everything changes once we’re faced with a dinner table; there are rules and expectations. I am aware I’m speaking from the position of being a white British person, so only from one limited cultural perspective, but I was taught about how meals had to be “balanced” to be healthy and to eat 5-a-day and all the other generic stuff. Even in the past few years, I’ve been handed “how to eat” type leaflets from medical professionals that were literally from the 80’s. It’s just not realistic to have one “right” way of eating, our bodies are so different. It also assumes the “right” way is based on White Western approaches to eating, assuming this is the “normal” way. It is not. We all need to find our own normal and not feel ashamed for this. Neurodiversity We can’t talk about ARFID, or any other eating disorder, without talking about neurodiversity. I use this term here to refer to the natural differences in the way everybody thinks and processes information. Through my own practice I’ve learnt the importance of looking through a neurodiverse, and intersectional, lens. Even working with people who are neurotypical there are benefits to this, as everyone has different communication and learning preferences. With ARFID, there can be sensory sensitives in many people, meaning that different textures of food, mix of foods, and variance of foods can make life very tricky. Think about how much fruit and veg can vary in texture (and taste) from day to day! There is no consistency, therefore no safety, in those foods at all, but with some crackers or a packet of crisps, it’s the same each time. For neurodivergent people (which in this sense I’m referring to autism and ADHD mainly), there can be a pressure to “mask” and try to “fit in”, which may mean added pressures and anxieties around eating “normally”. The idea that we have to help people fit in with what we perceive as a “norm” (which is often a position of privilege) is not acceptable, especially in the case of neurodivergent people and those with disabilities. The world needs to accommodate, not reinforce a “norm” which is inaccessible for many. This again can lead to self-blame and shame. The same is true for eating – the “healthy” and “right” way of eating is too limited to accommodate everyone, and to enforce this is potentially harmful to people. For some people, the pressure, expectations and feelings of not being “normal”, and self-criticism and shame that come from this, are arguably the issue more than the food they don’t want to eat. The pressure from others, especially on children struggling to eat (who have little autonomy and choice) can exacerbate the situation, which is often due to understandable concern for their loved one but is underpinned by “norms” and expectations of what they think they “should” eat. Acceptance Many people with ARFID want help to be able to widen their food options, reduce anxiety around food and live an easier life, so I’m not suggesting that people just accept the limitations as that’s not going to be realistic. But I feel it can be helpful to start building self-acceptance and reducing critical thoughts as this will help recovery and healing. Putting in boundaries with others, and unlearning some narratives around food might be important too. Safety is such a big part of this, in the sense that food needs to feel safe to eat, but also places and people need to feel safe too. For people with ARFID seeking help, they may be nervous about seeing professionals in case they are forced to eat, or met with judgement or dismissal. The main issue with ARFID is that it’s so different for everyone, so there are no specific ways to help. It would involve working on a case-by-case basis, in a person-centred way. It is important that the person feels they’re not being judged, but that they have control and can make choices for themselves. There are currently no evidence-based treatment recommendations for ARFID but some treatment options in the NHS can involve Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, or family therapy for young people, with nutritional support too. For many people, it may be difficult to get a diagnosis (or they may not feel safe to go to their GP in the first place) so they may opt to seek help privately. I work in an Integrative way, with a person-centred foundation, meaning I incorporate different theories and approaches but I am collaborative and adaptable to suit clients’ needs. This is not a “how to work with ARFID” list but there are some approaches which might be helpful:

A wider understanding of ARFID in society is needed and more literature on this subject. I’m pleased ARFID is the theme for Eating Disorders Awareness Week this year, and I hope we can keep the conversation going. If you have any helpful resources or training for professionals, do let me know. NEDDE are running an ARFID course for practitioners in April, more details here. To find out more about my counselling practice, click here. Both First Steps and BEAT offer support services for ARFID. Just also a big shout out to Dr Chuks and Bailey Spinn who recently wrote a fantastic book called “Eating Disorders Don’t Discriminate: Stories of Illness, Hope and Recovery from Diverse Voices” – check it out!

0 Comments

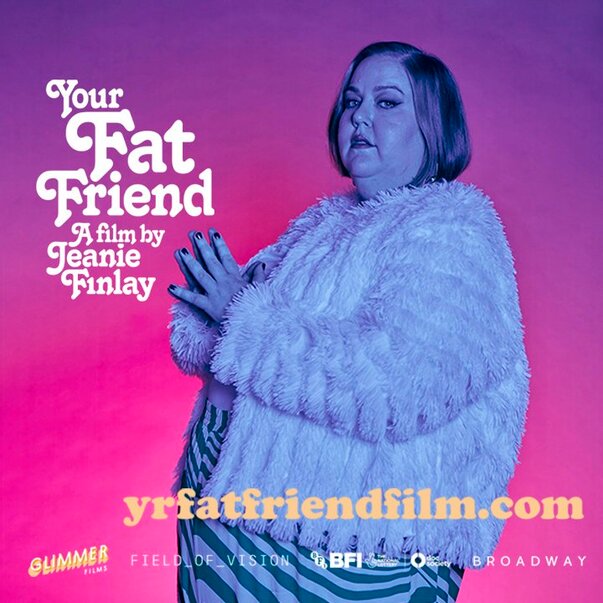

I recently saw “Your Fat Friend”, a documentary about Aubrey Gordon made by Jeanie Finlay. I’m a big fan of Aubrey’s work, her books, blogs and podcast - Maintenance Phase, and she’s been a huge influence on me both personally and professionally. I am a counsellor and trainer working with people struggling with eating, body image and the impact of weight stigma. I’m passionate about highlighting the importance of helping those in larger bodies with eating disorders, and training other counsellors in understanding disordered eating and weight stigma, and this film just lit even more of a fire in me. In the film, Aubrey talks about having an eating disorder and the barriers for fat people trying to access help, she says eating disorder treatment/support for fat people literally doesn’t exist. This broke my heart to hear, even though I’ve heard so many stories like this from people who have been judged, dismissed and turned away. I’ve worked for eating disorder charities in different roles for over 7 years now and it’s always disheartening to hear stories of being turned away from NHS services for not being “thin enough” and the assumptions made about fat people. As Aubrey says in the film, if a fat person has an eating disorder it is assumed that must be binge eating. This is absolutely not the case; people in smaller bodies can struggle with binge eating, and fat people can struggle with restrictive eating. Binge eating can often include restriction anyway (eating less than your body requires), it’s part of what keeps the cycle going – restrict, binge, feel guilty/ashamed, and double-down on restriction again. It’s called a binge cycle and can also be applied to dieting – diet, “fail” at the diet, shame, back to dieting. This is how diet companies make money (sometimes now not using the word diet, but “wellness” or some other fluff), because it’s never the diet’s fault, right? It’s ours for lacking willpower, being lazy/not good enough etc. This is why dieting does not “work”, it’s just creating more shame, more anxiety, more self-blame, and ultimately creating more eating disorders. Aubrey also mentions Atypical Anorexia, basically just the same as anorexia but not fitting the low BMI threshold to tick the box of being “sick enough”. This is extremely harmful as it’s stopping so many people from accessing services (though in the UK this is likely largely due to significant underfunding of ED services), and means we have no hope of “early interventions” which the NICE Guidelines state are so important for eating disorders. Being turned away for help, or anticipating not being able to get help, can often just exacerbate the disordered eating, with people feeling there is nowhere to turn. This was very much the sense I got from Aubrey talking about having nowhere to go as a fat person with an eating disorder. It’s so hard to have trust in professionals when they have all grown up in the same fatphobic, diet culture, and have little to no training in this. When I was training to become a counsellor I realised this was very much the case for our industry too – nobody talks about eating, body image, weight stigma or fatphobia, yet it is extremely likely all counsellors will encounter people affected by these issues at some point. This is why I am so passionate about this work and filling this gap – we must make it safer for fat people to access therapy. Counsellors must know about eating and body issues through an intersectional lens, looking at power, privilege, class and biases. Sadly, in my experience, this is not happening anywhere near enough as the industry is prominently white and middle class, and this is even more so in the eating disorder world. A huge amount of research into eating disorders, and treatment centres and charities, are run by thin, white, middle-class women, focussing on helping thin, white, female clients. There are so many people left out of eating disorder treatment, not only fat people but black people, disabled people, trans and non-binary people, and many more minoritized people. Treatment and therapy isn’t safe enough for so many people. This has to change. In all honesty, the difficulty I find in writing about all these issues is that I don’t want to scare people or put them off trying to find help and support. I want to raise awareness of what’s going wrong so we can work on changing it, but for individuals seeking help, I don’t want this to be another thing that reinforces the idea that there is no help for them. There is help, there are people doing great work out there, and I believe it is possible for fat people to access the help they deserve. As Aubrey says in the film, “you can’t self-love your way out of oppression” which I totally get, but you deserve help to be able to cope, as a bare minimum. There are ways to start healing. It may always be hard navigating the world as fat person but there are ways to build resilience and compassion for yourself, and help create a better relationship with food, if that’s what you would like. I’m holding in mind that people reading this may be either looking support for themselves (or individuals who are just interested) or some may be counsellors/therapists or professionals looking for what they can do. So I’ll suggest some ways counsellors/therapists/ED services can help, and if you are looking for support you can perhaps use these as green flags (good things) to look out for!

I am proud to work with people in larger bodies (and all kinds of bodies) who are struggling with a range of eating problems and body distress. Sometimes I feel like I’m the only person in their life who doesn’t tell them they need to lose weight or make them feel like their body is not good enough. We need more counsellors, therapists and people working in the eating disorder field to help fat people feel that they are safe, welcome, and cared for. I’m keen to hear other ways we can help fat people access help safely as I know there’s way more needed than just the tiny list above. We need to share ideas, so please let me know! Thanks for reading. If you’re interested in having counselling please head to my counselling page for more info. If you’re interested in my workshops and trainings, I’ll be offering more soon so check out my workshops page and sign up to my mailing list and I’ll let you know when more dates come up. Thanks! Your Fat Friend trailer: |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|