|

A couple of years ago I wrote an initial reflection on working with perpetrators of domestic abuse when I was relatively new to the work. Since then, sadly the service has closed as the funding ended. This is not uncommon in this field; victim services are barely funded enough so perpetrator services can be a hard sell. So, given this sad ending, I wanted to reflect on this amazing work and what I’ve learned about working with perpetrators, and about what we need to do as a society to help men. Due to the nature of this work, no names or identifying information about the organisation or individual involved will be used. I’m a counsellor in private practice but I worked three days per week for a domestic abuse charity, doing group and 1:1 work on a perpetrator programme. I started as a group facilitator and then I got more involved, doing assessments and also doing one-to-one Behaviour Change sessions. I was surprised that I could even do this work, I’d always been drawn to it but thought I was just being naïve at first! I remember when I first started training to be a counsellor, we were asked if there were any clients we wouldn’t want to work with. Some of my peers said offenders/perpetrators (especially those who had harmed children) and as much as I respected their choice, I became aware that I was one of the few who particularly wanted to work with these groups. They are the most stigmatized and shamed, and who arguably may need us the most. I knew if I could get into this work somehow, I definitely should. It felt so important. I thought the concept of perpetrator programmes was great; as well as helping people leave abusive relationships, we had an opportunity to go to the root of the problem and help break the cycle. It feels like our domestic abuse victim services are just firefighting at times, doing the very best they can do with the funding and resources available. Domestic abuse is about patterns of power and control, so when an abusive relationship ends, there’s always a risk that either person could enter into another abusive relationship. These are generational cycles which many people don't realise that they're in. I wanted to help break the cycles and help the ripple effect, ultimately to help partners, future partners, children and grandchildren be safer too. My first observation of a perpetrator group was eye-opening. I was struck by the level of openness and honesty from the group members. I also admired the challenges offered by the facilitators, whilst holding a non-judgmental and compassionate space. I knew it was for me instantly. I was worried I might be scared and would want to literally run out of the room, but something in me just felt right. For somebody who was a timid child being told by many to “be more assertive”, I surprised myself by becoming a confident, challenging facilitator! The most important part of this work was the support from the team. My co-workers, supervisor and manager made this possible; it’s crucial to have a good team to be able to “hold” this work and manage risk. I’ve always been fascinated by why people do what they do. I don’t believe that people are just “bad” or are born “evil” or “monsters”, it’s just not possible. People who hurt others have often been hurt themselves. They may have had difficult relationships, or sometimes struggle to have meaningful relationships at all. There can be attachment and child development issues, past abuse and trauma. The complexities and nuances of what makes a person harm others are complicated and different person-to-person, but everyone deserves the chance to be heard and shown respect and compassion. The perpetrator programme offered this balance of being challenged and held accountable, whilst being strengths-based, compassionate and empathic. Many perpetrator programmes are just for cis-gendered men, but this doesn’t mean other people aren’t abusive of course. There needs to be more provision for programmes for a range of genders, sexualities and relationship arrangements. However, there is barely enough for men at the moment, and men are the most common perpetrators of abuse. This can be a confronting thing to talk about, especially online, as there can be backlash, defensiveness and “what-about-ery”, e.g. “but what about all the men who are abused?” This is a valid point, but can often be used to derail the conversation about male violence. We need to name it to help solve the problem. In my view, patriarchal norms and expectations harm everyone. As a woman, I feel I was socialised to adhere to the male gaze, meaning I needed to try my best to be attractive to men and give them what they wanted. My self-worth was wrapped up in what men thought of me. I gave their opinion more worth than my own, about my own body! These messages came to me from films, TV, family, friends…it was the water I swam in so I never questioned it. It was just normal. When I started learning about feminism later, I had a lot of unpacking to do. I realised that I upheld unrealistic standards of myself, but also, I was helping uphold masculinity standards too. Masculinity comes with its expectations, norms and demands. On the programme we would explore the “man box”, all the things that keep men trapped in the expectations of their gender, and the consequences for stepping outside the box. The pressures and expectations can include, not being “emotional”, not crying, being tall and muscular, being “the provider”, not showing vulnerability etc. Sadly, this meant the men often had learnt to push down their emotions, as they were unacceptable. Many had never learnt how to talk about emotions and never had that modelled for them. Part of the magic of group work is having the space to talk to each other, which in turn helps model vulnerability and provides practice in communicating about emotions. It’s an experiential, powerful intervention, as well as the psychoeducation, exercises and discussion on the programme. These together, the relational group dynamics and the programme topics and themes each session, created an intense but very impactful intervention. It felt like such a gift and a privilege to do this work and witness this. As facilitators, our strength is in being compassionate but challenging. Trying to hold somebody accountable by making them feel belittled or told off is just not going to work. It triggers the shame that so many of these men have deep down, that is so hard to let out, let alone speak about. Their shame can feel too much, so it’s often the cause of defensive behaviours. When you’re not used to being vulnerable, it can feel terrifying. We needed to help hold this shame whilst they explored and worked on themselves and their behaviours. We often talked about the “pit of shit” (was “shame” but “shit” became more fun), and how getting out of it required them to clamber out onto the path of accountability. But it’s hard to climb out whilst stuck in the sticky, muddy shame, especially for those with low confidence and self-esteem. It brings a paradox for some who would consider these men not to be deserving of feeling better about themselves, but this is the very thing needed to climb out of the pit and take responsibility. We loved an iceberg on the programme. We’d draw the angry behaviours at the top (i.e. what you can see, e.g. shouting, slamming doors), with the underlying emotions below the surface, e.g. fear, vulnerability, shame. A theme I often noticed was jealousy. This often linked with underlying feelings of insecurity and low self-esteem. The controlling behaviours stemmed from the jealously and inadequacy, and fear of abandonment. This could have been impacted by experiences in previous relationships and likely caregiver relationships in early childhood. An insecure attachment can be a common factor with some men on these programmes, in my experience. Entitlement, in the context of being entitled to women’s bodies, may be more likely to stem from societal and cultural influences which tell men they have a right to women’s bodies. We see this a lot in the “manosphere” (men’s rights activists, incels etc) which many might argue is getting worse now we are in the “Andrew Tate era”. It seems the idea of being an “alpha” is becoming important again (which to me is men literally putting themselves in the constraints of the man box), and with this comes the idea of power over women (and other men). Ultimately, I believe so much of this is rooted in fear of losing power. Women and trans/non-binary people are taking up more space now and having more power, and this is seen as a threat to men. It’s not of course, it’s an opportunity for us to dismantle patriarchal and traditional gender norms and expectations, which would help us all. What it means to be “masculine” needs more flexibility and more empathy. We need positive male role models who can help other men, standing against harmful behaviour but in a way that doesn’t shame them. We need media literacy for children and young people to help understand and reduce the risk of online grooming into the “manosphere” and ethical use of pornography. We need women to stop upholding gender expectations on men too and support them to be able to feel safe to show emotions. We need to stop the increasing transphobia and make it safe for people to be themselves. We need better representation of vulnerable men on TV and in films. We need to stop normalising abusive and controlling behaviours in the media. We, as a society, have a lot of work to do. But we also need to have compassion and remember the humanity in people, and believe that some people are absolutely able to change. I’ve seen these changes happen; men have become better fathers, they’re able to understand themselves and their behaviours so much better, and they now model to their kids that it’s OK to be vulnerable, and how to take accountability. We need to keep breaking these cycles for generations to come. I did a talk with Online Events about this too, if you’d like to find out more or purchase a recording CLICK HERE. I also offer other workshops, please check out my workshops page for what’s coming up.

0 Comments

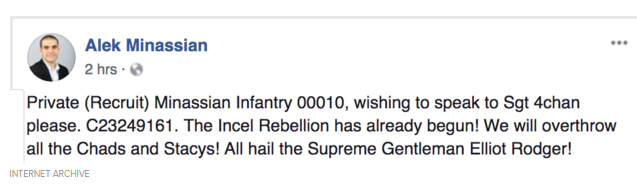

Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. On Monday 23 April, a man drove a van into a group of pedestrians in Toronto, killing 10 people and injuring 13 more. It later arose that this man was a self-proclaimed ‘incel’ having posted on social media just before the attack: ‘Chads’ and ‘Stacys’ refer to sexually active men and women. The attacker explained his angst in a video he made before the attack where he talked about still being a virgin and vowed to kill women for rejecting him. What is an incel?‘Incel’ is short for ‘involuntary celibate’ - they’re part of the Men’s Rights Activist (MRA) movement. The ‘manosphere’ is another name for the huge dark corner of the web filled with different factions of these misogynistic men. Although I’ve spent longer than I should’ve in the manosphere, even I don’t understand the crazy hierarchy of men’s rights activists, pick-up artists, incels and numerous other groups and divisions within the movement. It’s a scary part of the internet to venture, full of hatred and bitterness. Incels are predominantly straight white men who believe they’re entitled to sex. These men have little to no sex, unsuprisingly. They embrace their own helplessness at not being able to attract women and blame it on not being as attractive as the ‘chads’. They embody being the victim and become incredibly bitter towards the men who can get women, and the women who sleep with them. Why are incels like this? There are a lot of people on Twitter at the moment talking about how incels are terrible people, which is fair. However, I’m interested in why they act the way they do because this might help us learn something so we can help. Also, I’m aware that these men are very angry. Directing more anger and hate at them will only prove them right: they’re the victims and everyone is against them. They’re already angry because women won’t have sex with them, because other men are more attractive than them and because other people in society are gaining more power than them. All their actions are fear driven. Despite them playing the part of strong men, they’re often lonely and vulnerable. Dating is hard. There are lots of men who can’t get dates easily, but it’s not down to their appearance. It’s likely the bitter attitude of most incels that repels women. They’re in a vicious circle: not able to get women because of their attitude, but the rejection/fear of trying in the first place/having been hurt in the past, perpetuates that bitter attitude. Women are taking control of their own sex lives and patriarchal traditions are being dismantled. We are trying to give power to people who have never had it before - trying to give people a voice. These men have grown up thinking the straight white man is at the top – they rule the world. They are scared that giving power to another group means taking it from them. Again, it’s all rooted in fear. So incels are lonely men, sitting behind their computers complaining about how they’re not attractive enough to get women. When I think about this I see low self-esteem, low confidence and low self-worth. Many of these men may hang out online because they have social anxiety problems. Ultimately, anybody who goes around telling everyone they can’t get laid, is asking for help. They’re just asking for help in the wrong places. If many of these men have social anxieties or mental health issues it might be a daunting prospect to ask for help offline. They may not even have many friends. It makes sense that online forums are the ideal place to meet people in these circumstances. Unfortunately, these can be full of like-minded incels or MRAs encouraging each other’s hatred and anger. What these men are really looking for is a community, a support network and ultimately some help. How can we help incels?You may be thinking “no way, I don’t want to help these guys” but how can we try to make a difference if we simply throw hate back at them? We could create a future that helps bring young boys into a world where they can ask for help without being sucked into a potentially dangerous community. It’s not the old school MRA’s or incels that will drive vans into people or pick up a gun and storm into a school, it’ll be the younger ones or the more vulnerable men that do. Forums are a world where suddenly people understand them. I wrote a short story about this a few years ago called Manosphere, about a teenager - bitter about his ex-girlfriend - who turns to violence. I wrote it to demonstrate how easy it would be for someone desperate for help to get led down the wrong path. It was fiction but it this kind of thing now keeps happening in real life. Some incels are clearly experiencing anxieties they don’t know how to cope with alone, and violence - to themselves or others - is their only way out. What if they were able to ask for help in “real life” not online? What if men weren’t taught that women are sexual objects? What if they weren’t told to “man up” and they weren’t given toy guns to play with as kids? Children are constantly learning and all these things all have an impact. When men are taught from a young age that women are there just for their sexual gratification, and that they rightfully own the power, it’s no surprise that these expectations are not going to be reached. The irony behind the MRA movement is their major concerns over the high male suicide rates and lack of support for men’s mental health. MRAs are arch rivals of feminists, yet ironically they often want the same thing. If incels felt they were able to access support from a healthy, safe place, there could be a chance they could get the help they need. Difficulty forming relationships can be because of many problems in the past: they might’ve been hurt by girlfriend, or women in their family, or maybe they’ve been bullied because of their appearance at school. The way to unpick all of this is with a good therapist. It could be that some of these men have tried to access therapeutic services but they’re too expensive or the waiting lists are too long. This is why mental health needs to be a priority. It’s just as important as physical health.  We need to be teaching young boys not to channel their emotions as anger, but rather that it’s okay to show emotion and empathy - it’s not a sign of weakness. Gender equality is about not teaching girls to be princesses and not teaching boys that crying is weak – it ultimately helps everyone. Thanks for reading. Sending love to all affected by the Toronto tragedy. Let’s try to make the world a kinder place. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|