|

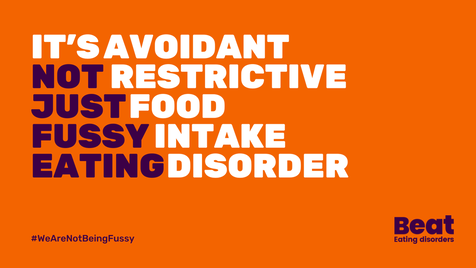

It's Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2024, and BEAT's theme is ARFID (Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder), which is what I'm going to attempt to write about today. I'm going to caveat this with I'm not an expert, but I don't think many people are given that there’s very little research, literature or training on ARFID. What there is tends to be about children and young people, mainly from a White Western perspective. So I'm writing this based on having worked with some people with ARFID (adults only) in my counselling practice, and from my own experiences. It’s important to note, that for people who do not have a diagnosis of ARFID (or any other eating disorder), your struggle is still absolutely valid and you are still worthy of help and support. What is ARFID? ARFID - Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder – is a lesser-known eating disorder, categorized in the 5th edition of the DSM-5 (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). ARFID is described as an “eating or feeding disturbance” which may include sensory sensitivity, fear of aversive consequences of eating, or lack of interest in eating. This can manifest in various ways, such as avoiding certain food textures, colours, or smells, experiencing a lack of appetite, or having a limited range of acceptable or safe foods. My personal experiences I describe my own experiences usually as "disordered eating" as I've fleeted around different difficulties in my life but never been diagnosed with an eating disorder. I never considered there was even an issue, until I started learning more about eating disorders, and learnt about the influence of diet culture and weight stigma in my life. When I learnt about ARFID, I could definitely relate with some of my experiences of being fearful of foods. I was fortunate enough to travel quite a long time in my 20’s, but was not so great on my guts. I had food poisoning numerous times and became anxious about what I could eat as almost everything seemed to make me feel nauseous, bloated and have a bad stomach. I saw various professionals - medical and holistic - many of whom seemed to want to tell me what not to eat. I did various elimination diets and nothing worked. I just got gradually more scared of what to eat. I even cut out tomatoes for a while, which for an avid pasta and pizza eater was really no good! My poor stomach has taken the brunt of most things in my life, emotionally and physically, which I manage on an ongoing basis still though it is much better now. It took me many years to start building up what I could eat again. It didn’t start with challenging myself to eat more foods, it started with finding more routine and stability when I moved back to the UK. I started having counselling, doing yoga and building up my relationship with myself, and food. I also had a lot of diet culture stuff I was trying to unpack, which was an added complexity. I didn't hate my body anymore but I certainly didn't love it. I was starting to be a little kinder to it at least. I felt brave enough gradually to try new things, but it’s scary when you’ve had bad experiences with food and it’s made you ill. I wanted to have variation in my eating and to reduce worrying about food, and some of that meant challenging diet culture narratives I’d picked up growing up, and societal ideas about “healthy” eating. I aimed for more of an intuitive eating approach and tried to get more in touch with my body, hunger signals and focus on what my body needs and how it felt instead of external influences. Like many people who have struggled with eating, I have foods and places I feel safer with, and I like to know what’s on the menu at places I eat beforehand. “Recovery” means different things to different people, there is no one-size-fits-all because everyone’s experiences are so nuanced and complex, but sometimes it just means managing a little better. Norms and expectations I feel way more at ease with food now, but I will never forget what the fear of eating feels like. I know what it's like to feel anxious about eating out, and eating at other people's houses. To be scared that there won't be anything for you to eat, and that people will judge you for being picky or difficult. To feel like you can’t eat like a normal person. It can be incredibly shaming to feel like the odd one out, that you're being too dramatic, and is easy to blame yourself for these things. This has a huge impact on your life; socially, at work, career choices etc. It can really hold you back. As a counsellor now working with eating disorders and disordered eating, I feel my lived experiences are important and beneficial in this work. Some people with eating difficulties will have experienced things very differently, but I still have some insight and I understand the turmoil, frustration, shame and various other underlying feelings associated with eating disorders. The main thing I’d like to let people know is that your struggle is valid, it’s a tough way to live, it is definitely not your fault and you absolutely do deserve help and support.

Normal eating? So what even is normal eating anyway and who makes the rules? Spoiler… “normal” eating doesn’t exist. Diet culture has a lot to answer for, but we also start learning about food from the moment we're born. Early childhood experiences and narratives around food can create templates which run through your whole life. We learn how to eat from others, which is heavily influenced by culture and society and “norms” can become ingrained. Some people, like myself, will learn that there are “good and bad foods” and that healthy equals being thin and fat is bad. As babies we cry and get fed, but then everything changes once we’re faced with a dinner table; there are rules and expectations. I am aware I’m speaking from the position of being a white British person, so only from one limited cultural perspective, but I was taught about how meals had to be “balanced” to be healthy and to eat 5-a-day and all the other generic stuff. Even in the past few years, I’ve been handed “how to eat” type leaflets from medical professionals that were literally from the 80’s. It’s just not realistic to have one “right” way of eating, our bodies are so different. It also assumes the “right” way is based on White Western approaches to eating, assuming this is the “normal” way. It is not. We all need to find our own normal and not feel ashamed for this. Neurodiversity We can’t talk about ARFID, or any other eating disorder, without talking about neurodiversity. I use this term here to refer to the natural differences in the way everybody thinks and processes information. Through my own practice I’ve learnt the importance of looking through a neurodiverse, and intersectional, lens. Even working with people who are neurotypical there are benefits to this, as everyone has different communication and learning preferences. With ARFID, there can be sensory sensitives in many people, meaning that different textures of food, mix of foods, and variance of foods can make life very tricky. Think about how much fruit and veg can vary in texture (and taste) from day to day! There is no consistency, therefore no safety, in those foods at all, but with some crackers or a packet of crisps, it’s the same each time. For neurodivergent people (which in this sense I’m referring to autism and ADHD mainly), there can be a pressure to “mask” and try to “fit in”, which may mean added pressures and anxieties around eating “normally”. The idea that we have to help people fit in with what we perceive as a “norm” (which is often a position of privilege) is not acceptable, especially in the case of neurodivergent people and those with disabilities. The world needs to accommodate, not reinforce a “norm” which is inaccessible for many. This again can lead to self-blame and shame. The same is true for eating – the “healthy” and “right” way of eating is too limited to accommodate everyone, and to enforce this is potentially harmful to people. For some people, the pressure, expectations and feelings of not being “normal”, and self-criticism and shame that come from this, are arguably the issue more than the food they don’t want to eat. The pressure from others, especially on children struggling to eat (who have little autonomy and choice) can exacerbate the situation, which is often due to understandable concern for their loved one but is underpinned by “norms” and expectations of what they think they “should” eat. Acceptance Many people with ARFID want help to be able to widen their food options, reduce anxiety around food and live an easier life, so I’m not suggesting that people just accept the limitations as that’s not going to be realistic. But I feel it can be helpful to start building self-acceptance and reducing critical thoughts as this will help recovery and healing. Putting in boundaries with others, and unlearning some narratives around food might be important too. Safety is such a big part of this, in the sense that food needs to feel safe to eat, but also places and people need to feel safe too. For people with ARFID seeking help, they may be nervous about seeing professionals in case they are forced to eat, or met with judgement or dismissal. The main issue with ARFID is that it’s so different for everyone, so there are no specific ways to help. It would involve working on a case-by-case basis, in a person-centred way. It is important that the person feels they’re not being judged, but that they have control and can make choices for themselves. There are currently no evidence-based treatment recommendations for ARFID but some treatment options in the NHS can involve Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, or family therapy for young people, with nutritional support too. For many people, it may be difficult to get a diagnosis (or they may not feel safe to go to their GP in the first place) so they may opt to seek help privately. I work in an Integrative way, with a person-centred foundation, meaning I incorporate different theories and approaches but I am collaborative and adaptable to suit clients’ needs. This is not a “how to work with ARFID” list but there are some approaches which might be helpful:

A wider understanding of ARFID in society is needed and more literature on this subject. I’m pleased ARFID is the theme for Eating Disorders Awareness Week this year, and I hope we can keep the conversation going. If you have any helpful resources or training for professionals, do let me know. NEDDE are running an ARFID course for practitioners in April, more details here. To find out more about my counselling practice, click here. Both First Steps and BEAT offer support services for ARFID. Just also a big shout out to Dr Chuks and Bailey Spinn who recently wrote a fantastic book called “Eating Disorders Don’t Discriminate: Stories of Illness, Hope and Recovery from Diverse Voices” – check it out!

0 Comments

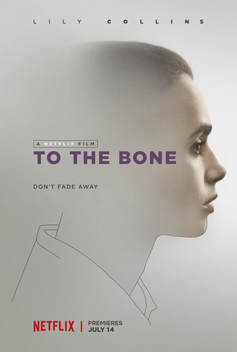

Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. Content warning: eating disorders To The Bone is somehow listed as a 'comedy drama' on IMDB. It's certainly not a comedy. Writer/director Marti Noxon was apparently influenced by her own eating disorder experiences and wanted to help raise awareness of the illness. Whether it does this in the right way is up for debate, and I’m still not entirely sure myself. As much as I’ve had a very weird relationship with food and a rather negative relationship with my body in general, but I’ve not had anorexia so it’s not fair for me to question if the film portrays it well. Though of course it’s also subjective, so To The Bone may have been Noxon’s experience of anorexia but other people may have a very different reality of it. Writing about mental health is tricky, especially for films. From my own experience of learning to write screenplays, it’s all about the three act structure and there’s an expectation to resolve all issues in the final act. This might be something relatively easy to do in a blockbuster action film (there's usually just a big fight and then the guy gets the hot girl) but when there are characters with complex mental health issues it’s hard to realistically resolve these in such a short time. In real life, unpicking trauma can take years. This, for me, was where To The Bone went wrong. There was a lot of focus on the illness (which is always risky as it can end up being a "how to" of eating disorders) and the recovery seemed to be done by way of a rather strange, quite rushed, epiphany sequence. And of course there was a boy involved too…uh oh…. There are only two notable male characters in this film and they hardly speak to each other. Technically you could say it passes the Bechdel test with flying colours. The Bechdel test asks if two women talk to each other about something other than a man, and although this was originally a useful test, it doesn’t stop women being overruled by men in films. In To The Bone, both men talk to her like crap, and their behaviour is never justified as such. It’s a particular gripe of mine when women are saved by men in films, but especially when it involves a mental illness. Often there just is no cure, another reason why it’s so hard to make a film which tells these stories in a satisfying, believable, responsible way. My first screenplay was about a young woman with depression and anxiety, and I’ve spent so long working on the ending to find that balance of it being hopeful but realistic. There are many ways people cope with having a mental illness but meeting someone and falling in love is often not the solution. This only puts pressure on another person to have to ‘fix’ them. Strength comes from inside yourself, not from Prince Charming. This is obviously why I don't write romance! Lilly Collins, who plays Ellen in To The Bone, apparently had an eating disorder herself. It’s no surprise then that she was brilliant in the role, but she did lose weight for it. We can’t say this was a bad choice on her part, because she’s a grown women and is responsible for her own body, but there’s no denying it was a risky move which might have potentially triggered her ED (eating disorder) again. Whilst we’re on the topic of triggers, the film does have calorie counting, weight loss tricks, disordered eating etc, and there are triggering images. We can’t tell people with ED not to watch this film, it’s their choice and many of them will choose to because it’s relevant to them. As with 13 Reasons Why, all Netflix can do is make sure their audience is warned about the content, otherwise the responsibility lies with the audience. We also can’t say these kinds of films and TV shows shouldn’t be made, because otherwise how would we start a dialogue around them? If this film was banned, where would the line be drawn when it comes to other films? On the other hand, there are dangerous images of thin women everywhere. For someone to play an anorexic woman in a film, she needs to be noticeably thinner than other women in films, and the ‘normal’ level is pretty bloody thin. It’s not hard to find ‘thinspiration’ in this world. Some people with anorexia might want to be triggered. You only need to step into the world of ‘pro-ana’ (pro anorexia) websites and thinspiration (sometimes called ‘thinspo’, or even ‘bonespo’) to see that being triggered can be a good thing for them. Ultimately there might be a horrible irony to Lilly Collin’s choice to lose weight for the role in that she may become an unintentional thinspo idol. In short, maybe this film is made for people who don’t know very much about eating disorders. There could be many benefits to parents or teachers, for instance, watching this to help recognise some things that people with anorexia may do. In this sense of raising awareness, maybe it works.  Look, it's Keanu Reeves. Look, it's Keanu Reeves. But let’s talk about Keanu Reeves. Keanu fucking Reeves. Personally, I think he has the screen presence of a lamppost. Apart from in the Bill and Ted films of course. (#NotAllKeanuReevesFilms) But maybe it’s not all his fault in To The Bone. It’s a mix of: a) the annoyingly privileged setting (they clearly got her into that residence ‘cos they’re loaded) b) patriarchal bullshit c) therapists always* being shit in films *Okay, so therapists in films are not all shit (#NotAllTherapists) but they need to be recognised in the script as being shit if they are. Take, for example, Robin Williams in Good Will Hunting. He’s not set up to automatically be the one we should trust because he’s working through his own issues. This works. What doesn’t work is when you get a weird, creepy therapist like Keanu Reeve’s character in To The Bone, who is treated like some kind of cult leader. His behaviour is then validated at the end when she returns to the house, and we’re supposed to believe that it’s a positive outcome for her. It’s great that she chooses to take steps towards her recovery, but to go back to a place run by such a weird creepy bloke is simply bonkers. Keanu/doctor/therapist/perv/cult leader is seen as radical because he says the word ‘fuck’ a few times. ‘Tell those negative thoughts to fuck off’ he says. So insightful and professional. Then he basically tells her to grow up and get over it, she goes away and has her little epiphany and then realises he’s right. The guy who thinks he can cure eating disorders by taking them to dance in some fake rain, is ‘right’ all along. She should’ve reported him, or at least gone to another clinic. But then, the boy was there. Prince Charming. The pompous British twat who came on to her but then instantly body shamed her when she said no. The one who tried to force-feed her chocolate. The one who sat on a tree branch in her epiphany dream – the bit where she was dressed up like some kind of born again Christian angel virgin and he made everything all better by telling her she was pretty. Couldn’t the stepsister have been sitting on that branch with her, Ellen wearing her usual clothes? Can she not take steps to recovery without there being a man there to help, and without having to wear less eyeliner? Then there was the mother and the moon. That strange, inappropriate feeding bit where her mother cradled her like a baby. I can see the theory behind that and it was nice to have a slight resolution to their seemingly turbulent relationship, but…really? And the moon…God knows. For a character who didn’t seem remotely spiritual, this ending was a little bit of a stretch for me. But the point is, she reaches the stage where she decides to follow the path to recovery. The intentions are good overall, and above all it’s a dialogue opener. The strength of the film was certainly in it’s strong female characters and family dynamic, showing how eating disorders effect the whole family. I hope this movie helps people learn a little more about an under-represented topic in film and will open conversations about eating disorders and how we can help people and families affected. If you or someone you know is affected by an eating disorder, here are some recommended websites: https://firststepsed.co.uk/firststepsed.co.uk/ https://www.b-eat.co.uk/ A note about triggering FEELING TRIGGERED IS NOT A WEAKNESS. If you’re the sort of person who mocks people for being triggered by things they watch or read, or uses the term ‘snowflakes’, you need to take a serious look at what kind of person you are. You wouldn’t laugh if that person was a relapsed drug addict, or if somebody had an injury which flared up. It proves how we don’t take mental health seriously enough as a society. Many people have had difficult experiences in their lives which can be easily triggered, bringing up difficult emotions. If you’re lucky enough not to have this problem then please recognise that not everyone is the same. It is not cool to laugh at somebody who is upset about something. It shows a lack of empathy, and that frankly you’re just a d*ck. Be excellent to each other! |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|