|

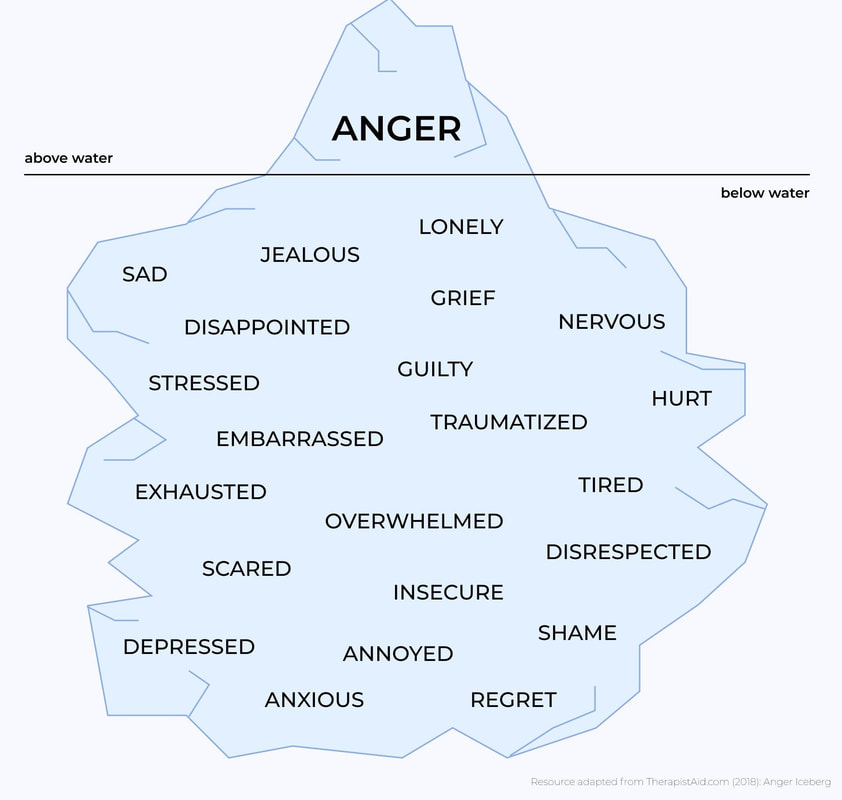

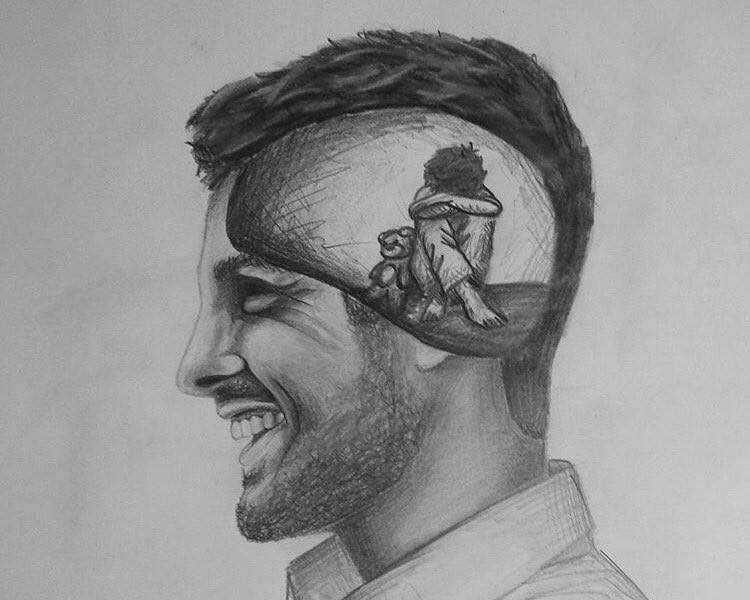

A couple of years ago I wrote an initial reflection on working with perpetrators of domestic abuse when I was relatively new to the work. Since then, sadly the service has closed as the funding ended. This is not uncommon in this field; victim services are barely funded enough so perpetrator services can be a hard sell. So, given this sad ending, I wanted to reflect on this amazing work and what I’ve learned about working with perpetrators, and about what we need to do as a society to help men. Due to the nature of this work, no names or identifying information about the organisation or individual involved will be used. I’m a counsellor in private practice but I worked three days per week for a domestic abuse charity, doing group and 1:1 work on a perpetrator programme. I started as a group facilitator and then I got more involved, doing assessments and also doing one-to-one Behaviour Change sessions. I was surprised that I could even do this work, I’d always been drawn to it but thought I was just being naïve at first! I remember when I first started training to be a counsellor, we were asked if there were any clients we wouldn’t want to work with. Some of my peers said offenders/perpetrators (especially those who had harmed children) and as much as I respected their choice, I became aware that I was one of the few who particularly wanted to work with these groups. They are the most stigmatized and shamed, and who arguably may need us the most. I knew if I could get into this work somehow, I definitely should. It felt so important. I thought the concept of perpetrator programmes was great; as well as helping people leave abusive relationships, we had an opportunity to go to the root of the problem and help break the cycle. It feels like our domestic abuse victim services are just firefighting at times, doing the very best they can do with the funding and resources available. Domestic abuse is about patterns of power and control, so when an abusive relationship ends, there’s always a risk that either person could enter into another abusive relationship. These are generational cycles which many people don't realise that they're in. I wanted to help break the cycles and help the ripple effect, ultimately to help partners, future partners, children and grandchildren be safer too. My first observation of a perpetrator group was eye-opening. I was struck by the level of openness and honesty from the group members. I also admired the challenges offered by the facilitators, whilst holding a non-judgmental and compassionate space. I knew it was for me instantly. I was worried I might be scared and would want to literally run out of the room, but something in me just felt right. For somebody who was a timid child being told by many to “be more assertive”, I surprised myself by becoming a confident, challenging facilitator! The most important part of this work was the support from the team. My co-workers, supervisor and manager made this possible; it’s crucial to have a good team to be able to “hold” this work and manage risk. I’ve always been fascinated by why people do what they do. I don’t believe that people are just “bad” or are born “evil” or “monsters”, it’s just not possible. People who hurt others have often been hurt themselves. They may have had difficult relationships, or sometimes struggle to have meaningful relationships at all. There can be attachment and child development issues, past abuse and trauma. The complexities and nuances of what makes a person harm others are complicated and different person-to-person, but everyone deserves the chance to be heard and shown respect and compassion. The perpetrator programme offered this balance of being challenged and held accountable, whilst being strengths-based, compassionate and empathic. Many perpetrator programmes are just for cis-gendered men, but this doesn’t mean other people aren’t abusive of course. There needs to be more provision for programmes for a range of genders, sexualities and relationship arrangements. However, there is barely enough for men at the moment, and men are the most common perpetrators of abuse. This can be a confronting thing to talk about, especially online, as there can be backlash, defensiveness and “what-about-ery”, e.g. “but what about all the men who are abused?” This is a valid point, but can often be used to derail the conversation about male violence. We need to name it to help solve the problem. In my view, patriarchal norms and expectations harm everyone. As a woman, I feel I was socialised to adhere to the male gaze, meaning I needed to try my best to be attractive to men and give them what they wanted. My self-worth was wrapped up in what men thought of me. I gave their opinion more worth than my own, about my own body! These messages came to me from films, TV, family, friends…it was the water I swam in so I never questioned it. It was just normal. When I started learning about feminism later, I had a lot of unpacking to do. I realised that I upheld unrealistic standards of myself, but also, I was helping uphold masculinity standards too. Masculinity comes with its expectations, norms and demands. On the programme we would explore the “man box”, all the things that keep men trapped in the expectations of their gender, and the consequences for stepping outside the box. The pressures and expectations can include, not being “emotional”, not crying, being tall and muscular, being “the provider”, not showing vulnerability etc. Sadly, this meant the men often had learnt to push down their emotions, as they were unacceptable. Many had never learnt how to talk about emotions and never had that modelled for them. Part of the magic of group work is having the space to talk to each other, which in turn helps model vulnerability and provides practice in communicating about emotions. It’s an experiential, powerful intervention, as well as the psychoeducation, exercises and discussion on the programme. These together, the relational group dynamics and the programme topics and themes each session, created an intense but very impactful intervention. It felt like such a gift and a privilege to do this work and witness this. As facilitators, our strength is in being compassionate but challenging. Trying to hold somebody accountable by making them feel belittled or told off is just not going to work. It triggers the shame that so many of these men have deep down, that is so hard to let out, let alone speak about. Their shame can feel too much, so it’s often the cause of defensive behaviours. When you’re not used to being vulnerable, it can feel terrifying. We needed to help hold this shame whilst they explored and worked on themselves and their behaviours. We often talked about the “pit of shit” (was “shame” but “shit” became more fun), and how getting out of it required them to clamber out onto the path of accountability. But it’s hard to climb out whilst stuck in the sticky, muddy shame, especially for those with low confidence and self-esteem. It brings a paradox for some who would consider these men not to be deserving of feeling better about themselves, but this is the very thing needed to climb out of the pit and take responsibility. We loved an iceberg on the programme. We’d draw the angry behaviours at the top (i.e. what you can see, e.g. shouting, slamming doors), with the underlying emotions below the surface, e.g. fear, vulnerability, shame. A theme I often noticed was jealousy. This often linked with underlying feelings of insecurity and low self-esteem. The controlling behaviours stemmed from the jealously and inadequacy, and fear of abandonment. This could have been impacted by experiences in previous relationships and likely caregiver relationships in early childhood. An insecure attachment can be a common factor with some men on these programmes, in my experience. Entitlement, in the context of being entitled to women’s bodies, may be more likely to stem from societal and cultural influences which tell men they have a right to women’s bodies. We see this a lot in the “manosphere” (men’s rights activists, incels etc) which many might argue is getting worse now we are in the “Andrew Tate era”. It seems the idea of being an “alpha” is becoming important again (which to me is men literally putting themselves in the constraints of the man box), and with this comes the idea of power over women (and other men). Ultimately, I believe so much of this is rooted in fear of losing power. Women and trans/non-binary people are taking up more space now and having more power, and this is seen as a threat to men. It’s not of course, it’s an opportunity for us to dismantle patriarchal and traditional gender norms and expectations, which would help us all. What it means to be “masculine” needs more flexibility and more empathy. We need positive male role models who can help other men, standing against harmful behaviour but in a way that doesn’t shame them. We need media literacy for children and young people to help understand and reduce the risk of online grooming into the “manosphere” and ethical use of pornography. We need women to stop upholding gender expectations on men too and support them to be able to feel safe to show emotions. We need to stop the increasing transphobia and make it safe for people to be themselves. We need better representation of vulnerable men on TV and in films. We need to stop normalising abusive and controlling behaviours in the media. We, as a society, have a lot of work to do. But we also need to have compassion and remember the humanity in people, and believe that some people are absolutely able to change. I’ve seen these changes happen; men have become better fathers, they’re able to understand themselves and their behaviours so much better, and they now model to their kids that it’s OK to be vulnerable, and how to take accountability. We need to keep breaking these cycles for generations to come. I did a talk with Online Events about this too, if you’d like to find out more or purchase a recording CLICK HERE. I also offer other workshops, please check out my workshops page for what’s coming up.

0 Comments

Everything you’ve always wanted to know about perpetrator programmes but were afraid to ask10/13/2022 I did a talk about my experiences at the Boys at the Crossroads conference on 12th October in Bristol, for more information, click here. I’m a group facilitator on a Domestic Violence Perpetrator Programme, which, if I ever got invited to fancy dinner parties, would probably go down like a lead balloon, as the saying goes. But really, people are usually intrigued, some are just less afraid than others to ask questions! This blog contains my honest reflections and experiences of being a group facilitator working with men who have used abusive behaviours. My workplace and the overarching research are mentioned, but these views are my own and are not of my employers, the researchers or the programme creators. Confidentiality is of the utmost importance here too, so I won’t be using any names or identifying factors for individuals, but will sometimes refer to “group members” generically as a collective when talking about patterns and themes. The language is binary due to the nature of the programme I work on as it’s for cis-gendered heterosexual men only, but I just want to flag up the vulnerability of trans and non-binary people being abused by partners and family members, also male survivors of abuse. None of these things are talked about enough. What is a perpetrator program? Programs and interventions vary in different areas, so my experience is only based on one; a 26-week intervention for men who have used abusive behaviours toward their partners or ex-partners. The weekly group sessions are 2.5hrs (with a short break) and involve a check-in at the start, followed by a led session based on themes and content from the programme manual. The sessions focus on different aspects of abuse, ranging from what abuse is (which is very important due to the misconception that only physical abuse is “real” abuse), sexual respect, anger management, attachment theory, CBT (cognitive behaviour therapy), emotional regulation, and more. It’s not something the men can do as a quick tick-box exercise to appease social services, it’s a long intervention and it’s challenging. It takes commitment, bravery, responsibility and accountability, and it involves dealing with a lot of difficult emotions. There are very few perpetrator programmes in the UK (though areas differ) as proving that they work and getting funding is difficult (hence the reason for the research study). There’s no doubt that prioritising helping victims/survivors is crucial when it comes to funding domestic violence services, but this can lead to a lack of help for perpetrators who want to change their behaviour, which in turn helps keep their partners (and children) safe. Perpetrator work is crucial for long-term change in helping victims/survivors and their children, to avoid them going into other relationships with the same patterns of behaviour. The safety of partners, ex-partners, children and future partners is at the heart of the programme. Why just men? A question I’m asked a lot (and I initially wondered this too) is “what about women?” Well, studies show that men are far more likely to be perpetrators than women. I know that statement will make some people feel uncomfortable and may prompt the response “but women can be abusive too”. This is true, but this response steers the focus away from the central issue. It’s similar to saying “all lives matter” - it de-centres the current problem, making it harder to focus on areas for change. Other perpetrator interventions in other areas may accommodate women, but the particular model this programme is based on (the Duluth model) involves content specifically to unpack masculinity and issues of power and control in a patriarchal society. It’s sometimes called a “pro-feminist” model for that reason, though I personally would argue that working on the basis that patriarchy and inequalities exist isn’t inherently “feminist” but is rather just highlighting an issue that affects us all. Naming the patriarchal imbalances doesn’t have to be an attack on men (as is often assumed about feminism) as it can help men too; after all, the patriarchy is damaging for everyone and places various harmful expectations on men. In a wider social context, it can be difficult to talk about male violence (especially on social media) without there being a lot of anger and defensiveness. We do still live in a society based on historical patriarchal values and that can make it difficult to have conversations about male violence as it can be met with de-railing and gaslighting tactics (albeit sometimes not conscious). Powerful people often fear losing their power and want to stay in control, so equality is risky for them. It’s the same with individuals who use abusive behaviour, it’s about power and control and the fear of not having it. We need to centre what’s important to be able to make a positive change in the world, and that means we need to put aside our discomfort with talking about male violence and abuse. This isn’t about pointing the finger or blaming men, but rather looking at how we can help. Patriarchal values can be harmful, with narratives about being a “real man” and expectations of being “the provider”. The messages about being strong and not showing emotion are prominent in the group, and we do work around “the man box” and masculinity expectations to unpack these. Many of the men on the programme have never been in spaces where they talk about emotions, and certainly never with other men. Many would say they’re not emotional people while forgetting that anger is an emotion too. We sometimes draw icebergs to demonstrate this, with anger at the top and all of the other emotions under the surface; anger being the emotion often seen as more “acceptable” for men to show. As a facilitator it’s been amazing to see how powerful group work with these men can be. They share experiences, model new behaviours, and both challenge and support each other. The group allows a safe and boundaried space to start to process these difficult emotions without the judgement or stigma they may otherwise face for having the label of “an abuser”. What got me into this work About ten years ago (at the time of writing) I got a job as a receptionist at a counselling organisation, and like many newbies was given tasks such as stuffing envelopes. We had a domestic abuse signposting pack, which contained flyers for a perpetrator programme, and it instantly struck me as such a crucially important thing. I would never have dreamed that ten years on I’d be working on one myself! I was just a self-conscious receptionist, I hated groups and I never thought I’d be able to become a group facilitator, or a counsellor too…but proving myself wrong has been pretty awesome I’ll admit! When I was learning more about feminism and inequalities, I became quite fascinated by men’s rights activists, incels, pick-up artists and “men going their own way” (MGTOW), in the dark depths of the internet known as the “manosphere”. It was part horrifying, part ridiculous, and mostly infuriating. I was channelling my anger and processing some of my stuff no doubt, but I was also curious about where these kinds of views and such blatant misogyny stemmed from. Since then, I’ve trained as a counsellor (at the time of writing in my final year) and have benefited hugely from being able to look at both systemic and individual factors and issues which lead to abuse, both in my own time, my work and through studies. Personal experiences in my own life have led me to have increased curiosity about perpetrators of abuse and sex offenders, and understanding these client groups has been helpful for my own healing too. I still had doubts about if I was being naïve, especially as most other counsellors (and trainee counsellors) I met did not want to work with these client groups. I wondered if I was kidding myself; wouldn’t I be terrified sitting in a room full of abusive men? Often I get the sense that certain client groups are seen as “too manipulative”, “untreatable” or “resistant” (interestingly, eating disorders are thrown into these categories too, which is my other line of work), but this has only sparked my interest and passion further. I wonder how much these labels were more about the practitioners and their views, judgements and societal stigma. Born evil? Words like “perpetrator” and “sex offender” hold a lot of stigma and seem to spark instant fear, leading to them being quickly deemed as “monsters”. There’s a sense that they will never change, or can’t change, or even that they were “born that way”. This is absolutely not the case, even serial killers and “psychopaths” were not “born evil”, despite what the media would portray. It’s instead a complex mix of genetic and environmental factors which can create disruptions in early brain development. People are not “born evil”, this is a myth perpetuated by society, potentially as a way to focus on the ”baddies” and ignore systemic societal issues and trauma which influence this behaviour. It takes curiosity and compassion to look beyond the labels and stigma, and holding strong boundaries, and being self-aware and reflective, so supervision (group and one-to-one) is very important in this work. Perpetrators and offenders have often been hurt and traumatised themselves. This is not an excuse for their behaviours but it’s important we look at the potential causes and influences. Experiences are different for every individual, but themes can include violence or controlling behaviour in their home when they were growing up, substance abuse, poverty, trauma, mental health issues, and systemic inequalities and discrimination such as racism. The first few years of life is a vulnerable time and we know from various literature that not having your needs met and not having enough love in the early stages of life is detrimental for brain development. (I suggest reading Sue Gerhardt’s book “Why Love Matters” if you’re interested to learn more). This in conjunction with attachment theory (Bowlby), means that a child may grow up with an insecure attachment based on not forming secure relationships with caregivers when they were babies, which becomes a template for their relationships and their whole lives. Part of the benefit of group work is to form and grow relational bonds through relationships with the facilitators and the other group members. My expectations when starting as a group facilitator

When you picture a perpetrator group, what do you see? Many new guys starting the programme have told us they expected Stella-swigging blokes in vests with tattoos on their necks. The men tell us they’re often surprised and relieved to find that it’s “normal guys” just like them. But sometimes, they may hope to find men “worse” than them, so they can position themselves as “not as bad as that guy”. This can happen with men who have not used physical abuse. They think they are not as bad as other guys because they’ve not been physical, but part of what we do on the programme is to go over all the other types of abuse and the impact – that emotional forms of abuse stick with women for years, if not their whole lives. There is no hierarchy of abuse in the group, they’re all there because their behaviour is impacting people negatively and they want to change that. I’ll be honest, I was absolutely terrified when I sat in on my first group. I knew that there would be men from all different backgrounds; a range of ages, working class and middle class, in different professions and from varying cultural background. But…how would I feel sitting with all these men that I knew had abused women? What if I freaked out? Cried? Got scared? I soon realised that many of these men were anxious and scared too, especially when starting the group. It can be terrifying for them, as they share the same fears around what to expect, but also there’s the worry of what we’re potentially going to put them through! Some of our role plays are hard-hitting, and we run empathy exercises (for instance asking them to sit in the role of their children and answer questions about the dad) which can bring up a lot for them, but it’s within a safe, contained and boundaried space. These men are dealing with a lot of shame, past trauma, attachment wounds, anxiety and many other factors, so safety and being “held” is vital. For me, being able to offer this “holding” and containment has been a real honour. I get to sit in a world that only a few see, and that feels like a real privilege and a gift. These men sit with really tough emotions and work really hard on their behaviour and self-development, and I find myself admiring and respecting them. This can create internal conflict in itself, forming relational bonds and feeling somewhat proud of the guys and the work they do, in the context of a society that says they’re “bad”. Many people have done bad things, but it doesn’t make them “bad” people. Underneath this behaviour there is often pain, shame and low self-esteem. The paradox for the men can be feeling as if they don’t deserve to improve their self-esteem, but this is needed in order to move out of the “pit of shame” as we call it (sometimes known fondly in our group as the “pit of sh*t”). My reflections one year on I started working for Splitz about a year ago (at the time of writing), which means I’ve done a full run of the programme (it’s continuous, so men join at different stages). The original members of the group who I started with have completed the programme, so there have been some heartfelt endings and it’s been lovely to hear the reflections from the men in their final group. I’m not involved in the research side of it, but if you ask me if perpetrator programmes work, then ABSOLUTELY. I have seen, felt and experienced it. Not everyone will be ready to change, but many are, and this can have an impact on their whole family. It’s so important that we see beyond labels, judgements and stigma to see the human being behind the behaviour. I like to believe that nobody is “untreatable” or “too resistant” or not worthy of help. Working on a perpetrator program helps take a bigger picture approach to domestic violence and abuse, by moving beyond the reactionary system currently in place, which often just involves helping victims stay safe in a dangerous situation. This just means the perpetrator continues their behaviour, and even if the victim can leave, they both risk getting into other abusive relationships in the future, so this approach isn’t helping to break cycles in the long-term. Helping perpetrators reflect on and change their behaviour is a vital longer-term approach to help break cycles of abuse, ultimately helping the next generations to come. Click here for domestic violence and abuse support organisations Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. TW: Domestic violence and abuse.. The world is football crazy at the moment. I hate football. The other day I was scrolling through Facebook when I saw this… Although the study was only conducted in Lancashire, it wouldn’t surprise me if it’s a snapshot of a problem throughout the whole country. “Incidents of domestic abuse rose by 38 per cent in Lancashire when the England team played and lost and increased by 26 per cent when the England national team played and won or drew compared with days when there was no England match. There was also a carry-over effect, with incidents of domestic abuse 11% higher the day after an England match.” – Lancaster University Here in the UK, we know and accept the actions that come along with football: binge drinking, fighting, chanting, and general obnoxious behaviour. Say “it’s just a game” to someone and you’re in danger of getting your head kicked in. So what makes this aggressive behaviour in football so prevalent? I used to live with some guys who were really into football. It was the first World Cup I’d been involved with, ‘involved’ meaning I didn’t care about the game but I was there for the booze. When England lost, my male friends were fuming. My female friends were disappointed, but my male friends were big balls of rage ready to explode. When we got home, one of them started punching a wall. We dragged him away and calmed him down, and then he started crying. It was like years’ worth of emotion all burst out of once. Looking back now, I see this is so much deeper. I used to question this particular friend a lot when it came to emotion and football. I used to tease him with the whole “it’s just a game” thing but sometimes I was worried he might actually punch me. He said football was the only time he cried. It was the only time it was allowed; it was pathetic for men to cry about anything else. I thought this was the pathetic concept and would take the piss out of him for crying over some guys kicking a ball around. But now I realise, when that’s the only thing you’re allowed to be emotional about, no wonder its important. Men’s Rights Activists are quick to point out that domestic violence victims can be male too, yet they often use this to derail arguments and take feminists down. They don’t seem to see that patriarchal rules and gender expectations have screwed us all over. Little boys are given toy guns and told to be strong. They see their favourite action film stars looking muscly and buff and quickly learn that being a man is about looking physically strong as well as acting strong. The world teaches boys that being kind and having empathy is weak and girly, and that emotions should be ignored, instead of teaching them how to feel and deal with them. So when a game comes along where all this pent-up emotion is allowed to come out (helped by a lot of beer) it literally will burst out. Little girls have masses of expectations put on them in terms being pretty and growing up to meet the harsh expectations of society, but at least we were allowed to cry. Domestic violence numbers are hard to quantify as many cases go unreported due to fear of speaking out. Any person of any gender can be a victim of domestic violence, but in the UK generally the majority are women. “In 2013-15, four times more women than men were killed by their partner/ex-partner” - Office for National Statistics (2016) Compendium – Homicide (average taken over 10 years) “Women experience domestic violence with much more intensity – 89% of people who experience four or more incidents of domestic violence are women” - Walby and Allen (2004) Domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking: Findings from the British Crime Survey It’s hard to use the term ‘toxic masculinity’ without seeming like I hate men. I don’t want to place any blame on men, or football. I want to question why, get to the root of the problem, and take steps towards positive solutions. We can’t just blame football and binge drinking, we have to examine our entire culture and the way we expect boys and girls to behave. We live in a world where people seem to believe gender fits neatly into two boxes and we have dress in a suitable way to prove which box we’re in so other people feel comfortable. People have difficulties understanding non-binary people – they feel the need to assess if they’re ‘really’ a man or a woman underneath. Does having a penis make somebody a man? Does fitting into your stereotypical view of masculinity make them a man? And why do you need to know so badly? It we really treated everybody equally, you wouldn’t need to know what kind of genitalia a person has in order to be able to talk to them like a human being. Football doesn’t turn somebody into a domestic violence perpetrator, but if they have a tendency to be aggressive, it might push them over the edge. We also have to remember that domestic violence isn’t always physical. There is emotional abuse (manipulation, coercive behaviour etc.), financial abuse and verbal abuse. It’s about control, which is why domestic violence is a feminist issue. The reason why I talk in terms of violent men towards women is because this is the most common, although abusive relationships can be between anyone of any gender. Living in a patriarchal society where men have the most power means we’ve all grown up seeing heterosexuality as the norm and male dominance as acceptable. In the media, they often depict domestic violence as a man with balled up fists and a woman cowering. It’s similar to how rapists are traditionally thought of as perverts who linger in dark alleys waiting for a young random girl to pounce on. This is not always the case. In both these instances, the man can often be someone the victim knows and loves. This view of the stereotypical ‘bad man’ often results in women being doubted when they come forward about rape, sexual abuse or domestic violence if the perpetrator doesn’t fit that stereotype. I once saw a couple arguing outside a pub with their three children watching. The man slammed her up against her car and was shouting in her face. The kids seemed surprisingly relaxed, like they’d seen it all before. I rang the police and reported the incident. There was a local shopkeeper who had been standing outside watching it all. I told him the police were coming and he shook his head at me. He told me I shouldn’t have called the police, it was no business of theirs. He said it was a family matter for them to sort out themselves. I was so saddened by his lack of care, but was well aware that his view would be a popular one with many people. Power dynamics in relationships are very complex. We’re influenced by our own identities, the expectations placed on us by our family and friends, and the pressure in the media to be attractive. Then when we're not happy all the time we’re sold the magic pill to make it happen. Many of us are not taught how to talk about emotions in relationships. Our society tells us a failed marriage is shameful, yet if we have a long-term job and moved on we’d put it on our CV and would be proud of it. “Happily ever after” is a lot of pressure. Relationships are hard and we all need a little help sometimes. Communication problems are the biggest issue I’ve seen working for a relationship counselling organisation for over five years. On my journey further into the body positivity world, I’ve joined a lot of Facebook groups. Many of the people are women and are married with children. Some of them have posted some appalling things their husbands have said to them: he doesn’t find her attractive anymore since the “baby weight stayed on” and saying she needs to “tone up a bit”. There were examples of men not supporting their wives when somebody else says something unacceptable about their weight. Many women excuse this behaviour by saying things like “he probably didn’t mean it like that”, “he doesn’t say this kind of stuff all the time”, “he was just in a bad mood”, “he was drunk”. In a similar way after a football game there may be the same excuses: “he was just upset because his team didn’t win”, “he was drunk”, “he’s not normally like this” and the saddest one “he’ll change”. Some people wonder why women stay with men who treat them this badly. I’m guessing many of these people have been lucky; they’ve maybe never been involved in any kind of domestic violence situation themselves and don’t understand the complexity of problems around controlling relationships. This view – of “why doesn’t she just leave?” places the focus on the woman having to do something about it, instead of challenging the behaviour of the man. This is also known as victim blaming. For me, being overweight meant that I always had to be on a diet because I thought I would only get a man if I was thin. When I didn’t lose weight, I realised I would have to settle for any guy who showed any interest - he would be the best I could get. Nobody else would ever like me, so I’d have to do whatever it takes to keep him. Many women stay with men who treat them badly for this reason – they’re scared they’ll never find anyone else and are terrified of being alone because society has told them they’re not good enough. Some women are also scared to leave in case their partner physically hurts them. Other women are bribed into staying because the man has control of their bank account. Many women feel it’s their own fault and think they deserve to be treated this way. There are literally millions of cases and reasons, often tied into complex mental health difficulties too. So next time you think about saying “she can do better” or “she should just leave” then please think again. These women don’t need to change, the culture needs to change. Our relationship ideals are strict and unrealistic, mainly from the impact of fairy tales and more recently, films. The message is: find “the one”, settle down and then be happy forever. The Fifty Shades saga is meant to be a bit of kinky fun but in fact is about a relationship involving two very messed up people - a young naive woman and an older, controlling, privileged, coercive man. These films are released on Valentine’s Day and celebrated as romantic. Everyone swoons over the alpha male, who seems to be a psychotic stalker. These films make light of terrible behaviour. It tells women that putting up with bad behaviour will pay off. This is another reason why women stay in abusive relationships, because they don’t realise it’s abusive – the bad behaviour has been normalised in our society. Domestic violence is a huge cultural problem which we can only hope to start chipping away at by teaching young people that it’s okay to be different. That they’re just as important as everyone else no matter what their shape, size, gender, sexuality or skin colour. It’s okay for people not to fit into the mould of being a boy or girl, it’s okay for boys to cry, and it’s okay to ask for help. We can’t pretend that emotions don’t exist – we’re human, we all have them. We need to be equipped with the tools when we’re younger to know how to deal with our emotions so that it doesn’t get stored up and come bursting out because of a football game. Freephone 24-Hour National Domestic Violence Helpline: 0808 2000 247 - Refuge TIGER (Teaching Individuals Gender Equality and Respect) For Relationship help: https://www.relate.org.uk/relationship-help |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|