|

Skinny jabs. Weight loss injections. The new miracle drugs to “tackle the ob*sity crisis” once and for all. Drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy are being hailed as wonder drugs. Oprah raves about weight loss drugs and says “ob*sity is a disease” so it’s not about willpower. This apparently can help get rid of weight stigma…by reinforcing weight loss and thin ideals? This doesn’t make much sense to me. “Ob*sity” is not a disease, nor a behaviour or an eating disorder. It’s a body size measure and there is wide range of people of varying degrees of health within that bracket. It’s not something that needs fixing. However, I understand that many people feel unhappy in themselves and want to make changes, though sadly this often becomes about making themselves smaller using any means possible. I’m not against people who choose to take weight loss intentions, in the same way that I’m not anti people who diet. When I use the term “anti-diet” I mean I stand against diet culture, the thin ideal and weight stigma/biases in our society as these are harmful to so many people. It’s important to make an informed choice, and how can we really do that when we are swimming in diet culture narratives? The decision to take weight loss drugs needs to be based on reliable information, and should you choose to go ahead, it needs to be done safely, through the correct channels and with plenty of support before and after. Having counselling before can help you explore your relationship with food and your body, as it may be that you’re experiencing disordered eating or negative body image thoughts. If this is the case, taking weight loss injections will not help – it will likely only drive the thoughts and feelings that underpin your relationship with food and make things worse. Weight loss injections: what are they and how do they work? Weight injections are for people in higher BMI (Body Mass Index) categories, and in the UK they are usually available through a referral to a weight management service. It’s meant to be more of a last resort, like weight loss surgeries, and only available for those who “really need it” i.e. higher weights. I don’t mention specific weights as this can be triggering and further reinforces weight stigma. BMI itself is very outdated and not fit for purpose – you can learn more about that in this article by Aubrey Gordon aka Your Fat Friend. Weight loss injections work by making people feel full for longer. The idea is, if you’re less hungry, you’ll eat less and that means you’ll lose weight. This may work in the short term whilst you’re on the medication, but when you come off it you will gain it back. However, eating less doesn’t necessarily equal thinness – lots of people in larger bodies have likely tried eating less, perhaps having tried every diet under the sun, and are not thin (if diets “worked” wouldn’t everyone be thin, right?) Even if people do lose weight they may not be thin, as for many people thinness is not just possible. Our weight is decided by many factors and genetics is a big part of that. If people can be “naturally slim” then people can also be “naturally fat”. Your body will work hard to keep you at a “set point range”, your body’s comfortable weight range, in a similar way to how our bodies regulate our temperature and our need to go to the toilet. Our bodies are clever and we should trust them but due to diet culture, many of us have lost that trust sadly. Do weight loss injections "work"? The long-term “success” of weight loss injections is not yet known as research has not been going long enough to be able to adequately tell. Whilst some diets and weight loss interventions can result in weight loss in the short-term weight is often gained back in the long run. In the UK, weight loss injections are only prescribed on the NHS for a maximum of 2 years, and one study has shown that people regain two-thirds of the lost weight within two years of stopping. Short-term side effects include headaches, nausea, sickness, diarrhoea, acid reflux, constipation and more. Long-term side effects of staying on weight loss injections for many years aren’t yet known, and due to fears of weight regain it is concerning how many people may try to stay on them for life. These drugs were first intended for people with diabetes, so there have been shortages recently since its growing popularity for weight loss. Celebrities, and thinner people generally, are using it to “drop those last few pounds”, many of whom can afford to pay for it privately. Purchasing weight loss injections can be expensive plus there are risks of purchasing them online. The risks of buying weight loss injections In the documentary, “The truth about skinny jabs” with Anna Richardson, she visits some private clinics in London where they were happy to prescribe weight loss injections, without even taking any health markers, and despite her not being fat. They did so with a hefty bill of course. Anna also experiments with buying weight loss injections online, which she does with alarming ease. The risks of this are many; you can’t trust what’s in them, you might get ripped off or scammed, and anyone young or vulnerable could potentially buy them including those with eating disorders. This is a very dangerous way of accessing these drugs, you really don’t know what you’re getting. People on social media also target people for sales and these are often scammers. If you decide to take weight loss injections please do so through the proper medical channels, and if you do not meet the criteria for them, do not take them. Body shame is big money The idea that being thinner equals happier, healthier and more respectable is the entire basis of diet culture. Companies thrive off the body shame people experience when they think they’re not thin enough (even if they’re not fat). A common myth is that people at higher weights are so because they eat too much. This idea is way too simplistic, it is not as basic as “calories in, calories out”. When it is seen as individual responsibility and just an easy “choice” to lose weight, it’s putting more blame and shame on people. Even if two people of different sizes ate exactly the same they could be completely different sizes. The idea that everyone has the ability to be thin, and that thinner is better, causes so much harm in our society and is a major driver for disordered eating. “The best-known environmental contributor to the development of eating disorders is the sociocultural idealization of thinness.” - NEDA Using weight loss injections only reinforces the thin ideal and the fear of weight gain and increases the harmful experiences of fatphobia and weight stigma. These drugs do not help people with their health behaviours, or other aspects associated with better health like reducing stress and better sleep. Weight loss injections offer the same enticing dieting promise that thinner equals happier and healthier, which is simply just not true. Ultimately, in the same way that every other new diet culture fad says they are “the one” that finally makes everyone thin, they’re not. There are lots of fat people in the world and we will always still be here. Eating disorders There are sadly too many people who are overlooked for having an eating disorder due to their body size. Many people may not recognise that their eating is “disordered” as diet culture has normalised restrictive eating, over-exercise and the pursuit of thinness “no matter what”. Due to myths and stereotypes about eating disorders, people often assume you need to be thin to have one, when in fact most people with eating disorders are not underweight. With disordered eating labels such as Atypical Anorexia (Anorexia but not at a low weight) and Orthorexia (a preoccupation with “healthy” or “clean” eating), the lines between eating disorders, dieting and “healthy eating” are becoming increasingly blurred. This, coupled with weight stigma, means that people are often prescribed/recommended weight loss interventions when this will likely only drive the disordered eating. A person who has struggled for a long time with dieting or disordered eating is not going to be helped by yet another thing that attempts to make them thin. The diet cycle thrives off shame, and every time an intervention fails, people blame themselves or their lack of willpower, when it’s not their fault at all. Diets are made to keep you coming back, diet companies wouldn’t make any money otherwise. Weight loss drugs, manufactured by big pharmaceutical companies, are also made so you stay on them, potentially costing you a fortune and taking on the unknown long-term risks as well as short-term side effects. Diet companies and big pharma do not care about your health. It’s all about money and they profit big time off your body shame. In conclusion… If you’re concerned about your health or have fears and anxieties about your weight, please consider exploring your relationship with food and yourself before any kind of weight loss attempts or drugs. Counselling can help, as well as learning more about disordered eating, diet culture, and body acceptance and intuitive eating. Eating and body image issues can have deeper food causes and influences which will not be helped with weight loss attempts, this just keeps the cycle going. To break the cycle and make lasting changes, a deeper exploration is needed. I offer counselling sessions online, please check out my counselling page for more info. I also offer workshops on disordered eating, body image and weight stigma, please check out my workshops page for more information.

0 Comments

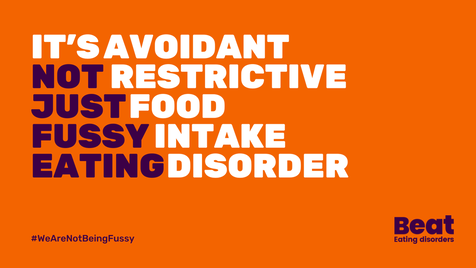

It's Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2024, and BEAT's theme is ARFID (Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder), which is what I'm going to attempt to write about today. I'm going to caveat this with I'm not an expert, but I don't think many people are given that there’s very little research, literature or training on ARFID. What there is tends to be about children and young people, mainly from a White Western perspective. So I'm writing this based on having worked with some people with ARFID (adults only) in my counselling practice, and from my own experiences. It’s important to note, that for people who do not have a diagnosis of ARFID (or any other eating disorder), your struggle is still absolutely valid and you are still worthy of help and support. What is ARFID? ARFID - Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder – is a lesser-known eating disorder, categorized in the 5th edition of the DSM-5 (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). ARFID is described as an “eating or feeding disturbance” which may include sensory sensitivity, fear of aversive consequences of eating, or lack of interest in eating. This can manifest in various ways, such as avoiding certain food textures, colours, or smells, experiencing a lack of appetite, or having a limited range of acceptable or safe foods. My personal experiences I describe my own experiences usually as "disordered eating" as I've fleeted around different difficulties in my life but never been diagnosed with an eating disorder. I never considered there was even an issue, until I started learning more about eating disorders, and learnt about the influence of diet culture and weight stigma in my life. When I learnt about ARFID, I could definitely relate with some of my experiences of being fearful of foods. I was fortunate enough to travel quite a long time in my 20’s, but was not so great on my guts. I had food poisoning numerous times and became anxious about what I could eat as almost everything seemed to make me feel nauseous, bloated and have a bad stomach. I saw various professionals - medical and holistic - many of whom seemed to want to tell me what not to eat. I did various elimination diets and nothing worked. I just got gradually more scared of what to eat. I even cut out tomatoes for a while, which for an avid pasta and pizza eater was really no good! My poor stomach has taken the brunt of most things in my life, emotionally and physically, which I manage on an ongoing basis still though it is much better now. It took me many years to start building up what I could eat again. It didn’t start with challenging myself to eat more foods, it started with finding more routine and stability when I moved back to the UK. I started having counselling, doing yoga and building up my relationship with myself, and food. I also had a lot of diet culture stuff I was trying to unpack, which was an added complexity. I didn't hate my body anymore but I certainly didn't love it. I was starting to be a little kinder to it at least. I felt brave enough gradually to try new things, but it’s scary when you’ve had bad experiences with food and it’s made you ill. I wanted to have variation in my eating and to reduce worrying about food, and some of that meant challenging diet culture narratives I’d picked up growing up, and societal ideas about “healthy” eating. I aimed for more of an intuitive eating approach and tried to get more in touch with my body, hunger signals and focus on what my body needs and how it felt instead of external influences. Like many people who have struggled with eating, I have foods and places I feel safer with, and I like to know what’s on the menu at places I eat beforehand. “Recovery” means different things to different people, there is no one-size-fits-all because everyone’s experiences are so nuanced and complex, but sometimes it just means managing a little better. Norms and expectations I feel way more at ease with food now, but I will never forget what the fear of eating feels like. I know what it's like to feel anxious about eating out, and eating at other people's houses. To be scared that there won't be anything for you to eat, and that people will judge you for being picky or difficult. To feel like you can’t eat like a normal person. It can be incredibly shaming to feel like the odd one out, that you're being too dramatic, and is easy to blame yourself for these things. This has a huge impact on your life; socially, at work, career choices etc. It can really hold you back. As a counsellor now working with eating disorders and disordered eating, I feel my lived experiences are important and beneficial in this work. Some people with eating difficulties will have experienced things very differently, but I still have some insight and I understand the turmoil, frustration, shame and various other underlying feelings associated with eating disorders. The main thing I’d like to let people know is that your struggle is valid, it’s a tough way to live, it is definitely not your fault and you absolutely do deserve help and support.

Normal eating? So what even is normal eating anyway and who makes the rules? Spoiler… “normal” eating doesn’t exist. Diet culture has a lot to answer for, but we also start learning about food from the moment we're born. Early childhood experiences and narratives around food can create templates which run through your whole life. We learn how to eat from others, which is heavily influenced by culture and society and “norms” can become ingrained. Some people, like myself, will learn that there are “good and bad foods” and that healthy equals being thin and fat is bad. As babies we cry and get fed, but then everything changes once we’re faced with a dinner table; there are rules and expectations. I am aware I’m speaking from the position of being a white British person, so only from one limited cultural perspective, but I was taught about how meals had to be “balanced” to be healthy and to eat 5-a-day and all the other generic stuff. Even in the past few years, I’ve been handed “how to eat” type leaflets from medical professionals that were literally from the 80’s. It’s just not realistic to have one “right” way of eating, our bodies are so different. It also assumes the “right” way is based on White Western approaches to eating, assuming this is the “normal” way. It is not. We all need to find our own normal and not feel ashamed for this. Neurodiversity We can’t talk about ARFID, or any other eating disorder, without talking about neurodiversity. I use this term here to refer to the natural differences in the way everybody thinks and processes information. Through my own practice I’ve learnt the importance of looking through a neurodiverse, and intersectional, lens. Even working with people who are neurotypical there are benefits to this, as everyone has different communication and learning preferences. With ARFID, there can be sensory sensitives in many people, meaning that different textures of food, mix of foods, and variance of foods can make life very tricky. Think about how much fruit and veg can vary in texture (and taste) from day to day! There is no consistency, therefore no safety, in those foods at all, but with some crackers or a packet of crisps, it’s the same each time. For neurodivergent people (which in this sense I’m referring to autism and ADHD mainly), there can be a pressure to “mask” and try to “fit in”, which may mean added pressures and anxieties around eating “normally”. The idea that we have to help people fit in with what we perceive as a “norm” (which is often a position of privilege) is not acceptable, especially in the case of neurodivergent people and those with disabilities. The world needs to accommodate, not reinforce a “norm” which is inaccessible for many. This again can lead to self-blame and shame. The same is true for eating – the “healthy” and “right” way of eating is too limited to accommodate everyone, and to enforce this is potentially harmful to people. For some people, the pressure, expectations and feelings of not being “normal”, and self-criticism and shame that come from this, are arguably the issue more than the food they don’t want to eat. The pressure from others, especially on children struggling to eat (who have little autonomy and choice) can exacerbate the situation, which is often due to understandable concern for their loved one but is underpinned by “norms” and expectations of what they think they “should” eat. Acceptance Many people with ARFID want help to be able to widen their food options, reduce anxiety around food and live an easier life, so I’m not suggesting that people just accept the limitations as that’s not going to be realistic. But I feel it can be helpful to start building self-acceptance and reducing critical thoughts as this will help recovery and healing. Putting in boundaries with others, and unlearning some narratives around food might be important too. Safety is such a big part of this, in the sense that food needs to feel safe to eat, but also places and people need to feel safe too. For people with ARFID seeking help, they may be nervous about seeing professionals in case they are forced to eat, or met with judgement or dismissal. The main issue with ARFID is that it’s so different for everyone, so there are no specific ways to help. It would involve working on a case-by-case basis, in a person-centred way. It is important that the person feels they’re not being judged, but that they have control and can make choices for themselves. There are currently no evidence-based treatment recommendations for ARFID but some treatment options in the NHS can involve Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, or family therapy for young people, with nutritional support too. For many people, it may be difficult to get a diagnosis (or they may not feel safe to go to their GP in the first place) so they may opt to seek help privately. I work in an Integrative way, with a person-centred foundation, meaning I incorporate different theories and approaches but I am collaborative and adaptable to suit clients’ needs. This is not a “how to work with ARFID” list but there are some approaches which might be helpful:

A wider understanding of ARFID in society is needed and more literature on this subject. I’m pleased ARFID is the theme for Eating Disorders Awareness Week this year, and I hope we can keep the conversation going. If you have any helpful resources or training for professionals, do let me know. NEDDE are running an ARFID course for practitioners in April, more details here. To find out more about my counselling practice, click here. Both First Steps and BEAT offer support services for ARFID. Just also a big shout out to Dr Chuks and Bailey Spinn who recently wrote a fantastic book called “Eating Disorders Don’t Discriminate: Stories of Illness, Hope and Recovery from Diverse Voices” – check it out! I recently saw “Your Fat Friend”, a documentary about Aubrey Gordon made by Jeanie Finlay. I’m a big fan of Aubrey’s work, her books, blogs and podcast - Maintenance Phase, and she’s been a huge influence on me both personally and professionally. I am a counsellor and trainer working with people struggling with eating, body image and the impact of weight stigma. I’m passionate about highlighting the importance of helping those in larger bodies with eating disorders, and training other counsellors in understanding disordered eating and weight stigma, and this film just lit even more of a fire in me. In the film, Aubrey talks about having an eating disorder and the barriers for fat people trying to access help, she says eating disorder treatment/support for fat people literally doesn’t exist. This broke my heart to hear, even though I’ve heard so many stories like this from people who have been judged, dismissed and turned away. I’ve worked for eating disorder charities in different roles for over 7 years now and it’s always disheartening to hear stories of being turned away from NHS services for not being “thin enough” and the assumptions made about fat people. As Aubrey says in the film, if a fat person has an eating disorder it is assumed that must be binge eating. This is absolutely not the case; people in smaller bodies can struggle with binge eating, and fat people can struggle with restrictive eating. Binge eating can often include restriction anyway (eating less than your body requires), it’s part of what keeps the cycle going – restrict, binge, feel guilty/ashamed, and double-down on restriction again. It’s called a binge cycle and can also be applied to dieting – diet, “fail” at the diet, shame, back to dieting. This is how diet companies make money (sometimes now not using the word diet, but “wellness” or some other fluff), because it’s never the diet’s fault, right? It’s ours for lacking willpower, being lazy/not good enough etc. This is why dieting does not “work”, it’s just creating more shame, more anxiety, more self-blame, and ultimately creating more eating disorders. Aubrey also mentions Atypical Anorexia, basically just the same as anorexia but not fitting the low BMI threshold to tick the box of being “sick enough”. This is extremely harmful as it’s stopping so many people from accessing services (though in the UK this is likely largely due to significant underfunding of ED services), and means we have no hope of “early interventions” which the NICE Guidelines state are so important for eating disorders. Being turned away for help, or anticipating not being able to get help, can often just exacerbate the disordered eating, with people feeling there is nowhere to turn. This was very much the sense I got from Aubrey talking about having nowhere to go as a fat person with an eating disorder. It’s so hard to have trust in professionals when they have all grown up in the same fatphobic, diet culture, and have little to no training in this. When I was training to become a counsellor I realised this was very much the case for our industry too – nobody talks about eating, body image, weight stigma or fatphobia, yet it is extremely likely all counsellors will encounter people affected by these issues at some point. This is why I am so passionate about this work and filling this gap – we must make it safer for fat people to access therapy. Counsellors must know about eating and body issues through an intersectional lens, looking at power, privilege, class and biases. Sadly, in my experience, this is not happening anywhere near enough as the industry is prominently white and middle class, and this is even more so in the eating disorder world. A huge amount of research into eating disorders, and treatment centres and charities, are run by thin, white, middle-class women, focussing on helping thin, white, female clients. There are so many people left out of eating disorder treatment, not only fat people but black people, disabled people, trans and non-binary people, and many more minoritized people. Treatment and therapy isn’t safe enough for so many people. This has to change. In all honesty, the difficulty I find in writing about all these issues is that I don’t want to scare people or put them off trying to find help and support. I want to raise awareness of what’s going wrong so we can work on changing it, but for individuals seeking help, I don’t want this to be another thing that reinforces the idea that there is no help for them. There is help, there are people doing great work out there, and I believe it is possible for fat people to access the help they deserve. As Aubrey says in the film, “you can’t self-love your way out of oppression” which I totally get, but you deserve help to be able to cope, as a bare minimum. There are ways to start healing. It may always be hard navigating the world as fat person but there are ways to build resilience and compassion for yourself, and help create a better relationship with food, if that’s what you would like. I’m holding in mind that people reading this may be either looking support for themselves (or individuals who are just interested) or some may be counsellors/therapists or professionals looking for what they can do. So I’ll suggest some ways counsellors/therapists/ED services can help, and if you are looking for support you can perhaps use these as green flags (good things) to look out for!

I am proud to work with people in larger bodies (and all kinds of bodies) who are struggling with a range of eating problems and body distress. Sometimes I feel like I’m the only person in their life who doesn’t tell them they need to lose weight or make them feel like their body is not good enough. We need more counsellors, therapists and people working in the eating disorder field to help fat people feel that they are safe, welcome, and cared for. I’m keen to hear other ways we can help fat people access help safely as I know there’s way more needed than just the tiny list above. We need to share ideas, so please let me know! Thanks for reading. If you’re interested in having counselling please head to my counselling page for more info. If you’re interested in my workshops and trainings, I’ll be offering more soon so check out my workshops page and sign up to my mailing list and I’ll let you know when more dates come up. Thanks! Your Fat Friend trailer: Everything Now: what does it get right about eating disorders and where does it fall short?11/19/2023 Spoilers! Everything Now is a coming-of-age drama comedy on Netflix, with a protagonist in eating disorder recovery. If you haven’t seen it, maybe go and watch it and come back, or if you’re not fussed about spoilers or have no intention of watching it and want to keep reading, then crack on! I’m a counsellor and I work with people with eating disorders, disordered eating and body image problems. I’ve worked for eating disorder charities for over 7 years now, but this does not make me an expert, these are just my opinions on the show and how they dealt with the topic. Firstly, Everything Now passed the basic bare minimum test… not showing triggering eating disorder images/scenes. When they included some ED behaviours, they were off camera and they included a warning before the episode (and they included help resources after each episode too). This already makes this show better than most other things about eating disorders, but the bar was pretty low. BEAT have some media guidelines which should be utilised by any media outlet, filmmaker or creator, but sadly this has not always been the case, as we see with shock-factor eating disorder tabloid articles, and in films such as To the Bone, which shows specific eating disorder behaviours and images of very thin bodies. Everything Now not only avoided this, they didn’t portray the protagonist, Mia, as being someone who just wants to be skinny to copy influencers on social media. This lack of emphasis on body image and vanity is refreshing, and the show demonstrates throughout that eating disorders are so much more than just negative body image or a diet gone too far. I also loved the casual queerness, by that I mean they never had to explain anyone’s sexuality, and didn’t assume heteronormativity. The show really portrayed the push-pull of recovery well, by this I mean to need to be recovered and “better” ASAP, whilst also struggling to let the eating disorder (which provides a sense of safety) go. Everything Now goes slightly against the usual trope of the thin white girl with anorexia, telling a lesser-seen narrative of a queer mixed-race woman. This was very much needed, however it still focuses on thin, rich, privileged families and barely mentions the impact of race, class and culture, an important missed opportunity in my view. This may have been something to do with it being written by Ripley Parker, who has two famous parents. It's as if they tried to make the characters less middle-class, perhaps to make it more accessible for an American audience (perhaps aiming for Sex Education vibes). This was jarring for me when seeing their homes and realising how wealthy they all were, and it’s as if they tried to ignore this or presented those kinds of homes as “normal”. In one part, the parents refer to how much they spent on Mia’s recovery. This sadly does position the story from the usual middle-class privileged lens, focussing on a thin person with anorexia who can afford a high standard of care. I’d love to see a gritty drama about a working-class person in a larger body with an eating disorder but that’d just involve them on a waiting list for months/years while their GP gives them a leaflet on “healthy eating”. Maybe not so entertaining. Sadly, I’ve heard many stories of this happening. Eating disorder treatment is predominantly for thin privileged people – these are the people who are researched, and who “gold standard” treatments are made for. It maintains the cycle of ED treatment for thin, middle-class people, created by thin middle-class people. I’ve heard many tales of people being told “we won’t let you get fat” and exercises that attempt to prove to the person that they’re not fat so they’re okay, such as the body tracing exercise in the show (which is inherently fatphobic, risky, and potentially so harmful and therefore unethical). In my personal experience, I’ve felt that conversations about fatphobia, race and class are not welcomed in the eating disorder world. There seems to be a complete silence around the very apparent weight stigma and reinforcement of fatphobia in treatment, which makes absolutely no sense considering that fear of fatness is part of many eating disorders. It’s a barrier for so many people needing help, the majority of which are not underweight. Anorexia is one of the less prevalent eating disorders, though it does have the highest mortality rate. In reality, many people with eating disorders are in larger bodies. Due to assumptions, weight stigma and fatphobia, so many people in larger bodies are not getting the help they deserve or worse, are told to lose weight, which will only make the disordered eating worse. One of the most interesting aspects of the show for me was relationships (but I would say that of course, I’m a counsellor!) The nuance of the parents’ characters, her relationship with her brother (shame it was only in one episode) and the friendship group were interesting. The parents were portrayed as trying their best, attentive and loving at times but not perfect. There’s no such thing as perfect parenting, it’s just “good enough”. In attachment theory, having a good enough parent means that as a baby you can form good enough attachment bonds, which are like templates for future relationships. Although eating disorders can be associated with trauma, this doesn’t necessarily mean a traumatic event or any major abuse or neglect. Instead, it may be to do with attachment and bonding in the early years, and how this impacts brain development, relationship with food and relationships with others. Eating disorders can often be tied into relationship wounds like this, and I might speculate in Everything Now that the mother-daughter relationship is an integral part. I would have liked to have known more about Mia’s childhood and seen more of her early relationship with her mother, but that’s just me itching for more therapeutic fodder! I got excited when they had the family therapy session and thought the defensiveness and awkwardness all around was well done and realistic. Family therapy is often part of treatment for young people with eating disorders due to the amount it impacts the whole family, but is difficult, uncomfortable and challenging for many. It’s important for parents and siblings to be involved as the relationships are so deeply affected, portrayed well with Mia and her brother, I only wish this had been woven throughout the series as it was jarring for just one episode. I particularly liked the part in the family therapy scene where the mum talks about young girls and TikTok and the others roll their eyes. This was a great way of busting the "social media creates eating disorders" myth but also showing the defensiveness that can come up for parents. This is certainly not a criticism of parents, when I say defensiveness I refer to the very understandable responses to feeling difficult emotions, which is understandable given their child has an eating disorder. Many parents can feel blamed, shamed, guilty, responsible for not being able to help their child, or even for being the reason their child has an eating disorder. There is never one reason why someone develops an eating disorder (there are biological, societal and psychological influences) so it can never be solely a parent’s fault. We do all live in a weight-biased diet culture though, so it may be that some parents benefit from reflecting on their role in the situation, and maybe even consider their own relationship with food, views about larger bodies and any food rules in the home. Even if this is not the case, the relationship in the family will need to heal and trust needs to be rebuilt. It’s tough for everyone involved and I think this was depicted well in Everything Now. There was a focus on the impact on family and friends, and how they were trying to protect Mia by keeping things from her. This of course was to avoid hurting her, though backfired as Mia just lost more trust and felt isolated as they’d lied. I’ve seen people on social media saying Mia isn’t a very nice person… not that I agree with this, but it’s difficult to be a nice person when you’re suffering, isn’t it? The idea that people with mental health problems or who have been traumatised should be quietly crying and be nice is just not realistic. Traumatised people often don’t act in nice ways, it’s why some of the most traumatised people in the world are in prison. Empathy often only seems to extend to people who are suffering in a nice, polite, socially acceptable way, but this keeps us as a society in a trap of ostracising and shaming the most hurt and marginalised people. Mia apologising at the end to her friends left me conflicted; why should she have to apologise for being the one suffering? I wondered what message that gave to the audience, for people supporting others with eating disorders, but also anyone in recovery themselves. This could potentially reinforce the shame of “look at how you hurt people”, which is not exactly a motivator for recovery. Eating disorders are shrouded in stigma and shame, and “feeling ashamed of being ashamed” as Mia’s voiceover so eloquently highlighted. Just also a quick note about Cam and the one episode where he seemed to be quite preoccupied with his body and muscles. This was jarring and strange in one episode only and seemed like a missed opportunity to explore muscle dysmorphia. Not “naming” this in the show could almost normalise it, so it’s a shame it wasn’t woven through the series. It may also have been confusing to people that Mia has anorexia but is heard vomiting (purging), as this may be confused with bulimia. There is a purging subtype of anorexia, so this likely what Mia was being shown to have. Overall, although this was a good show, there were other missed opportunities, largely around the intersection of racism, sexuality and class. In my view, eating disorders are always entangled in socio-cultural ideals and expectations, and an intersectional view is required. Eating disorders are largely tied into people's identities, so recovery means exploring the parts of the self, and building trust again in their body, and in the relationships around them. However, these conversations aren’t even happening in the real-life eating disorder world, and treatment is mostly geared towards thin white middle-class people with anorexia, so it’s a lot to ask for a TV show. Everything Now is at least a slightly new approach to eating disorder narratives, done in a respectful, responsible way, and I hope it will help lead to more nuanced conversations around eating disorders. Thanks for reading! I offer online counselling sessions, workshops and consultancy - please click to find out more. It’s that time of year again when the adverts start popping up: Slimming World, Noom “we’re-definitely-not-a-diet” diet scammers, and various other teas, pills, workouts, gyms and all the other money-grabbing companies trying to shame you. There are a lot of expectations and pressure to make changes, be better, fitter, healthier, more successful… BUY MORE STUFF! So here’s your friendly reminder…you don’t have to do any of that. If you choose to, that’s up to you, but you don’t have to. Sometimes the kindest thing to do for yourself is to not do anything at all. Maybe you don’t need to change yourself, and the effort of trying to do so is stressful in itself. Many people see Christmas time as a “free pass” to eat what they want – and good for you! BUT…what happens in January then? This time of year can bring about feelings of guilt and shame, and negative thoughts about yourself and your body. For some people, this can lead to disordered eating. Whether you have an eating disorder, or you struggle with food a bit, or it’s more about not liking your body – all of these concerns are valid. Instead of punishing yourself, you deserve help and support. People can be in a vulnerable place to be lured into the diet-scammers territory when they’re not feeling good about themselves. Trust me – they don’t care about your health, they are just about making money. If you like to make New Years Resolutions, how about trying to make them without weight loss in mind? Maybe your resolution could be to be kind to yourself and work on self-acceptance. Maybe you don’t need to make resolutions at all! I remember at school going back after Christmas and being asked to share our New Years Resolutions. I never felt like I fit in so of course I jumped on the bandwagon, and what’s the thing I knew I was expected to say? To lose weight. It was the only acceptable answer as a fat girl. There’s an expectation for fat people to constantly strive to be thin. We’re expected to dedicate our lives to worrying about our bodies, trying different diets til we find “the one” that works (spoiler alert – none of them work!) Eventually, I decided I wasn’t going to stand for that anymore. I could have spent my whole life trying to change my body, but instead I chose to work on accepting it. I’ll be honest and say I don’t think I “love” my body, but it’s a life-long work in progress. I just know I’m glad I made the choice to put my wellbeing first instead of paying money-making diet scammers with empty promises. Body acceptance isn’t easy but neither is dieting. If you’ve spent a long time dieting, I get it. It’s got such a pull and a strong hold over so many people. But you deserve help and support, not to continue to be body shamed by companies, adverts, people on the internet, medical professionals or anyone else. Sometimes, the best way to priorize your health is to start by being compassionate to yourself (but also health isn’t a moral obligation and you don’t owe anyone!)

My tips for being kinder to yourself in 2023:

I’ll be running more body acceptance workshops and will be opening my counselling practice later this year, please get in touch or join my mailing list for more info. “Eating disorders can affect anyone of any shape or size.” “Eating disorders don’t discriminate.” You may have seen these statements online and most people would agree, right? But in reality, is this ethos really working in practice? When plus-size model Tess Holliday spoke out about having anorexia, people on social media lost their minds. It seemed impossible for people to comprehend someone in a larger body restricting their eating. After all, our society teaches “eat less, move more” as the simple equation for weight loss, so there was an assumption that she must be lying because if she was really restricting, how could she possibly still be fat? Of course this resulted in a lot of online trolling for Tess, and in turn the underlying reinforcement of the idea that only thin people can have restrictive eating disorders. When I say restrictive eating disorders, I’m referring to Anorexia and Bulimia. I think many people automatically picture a thin person, usually white, young and female, associated with these eating disorders. Often, fat people are associated with binge eating, but in reality thin people can binge and fat people can restrict. Many people aren’t familiar with the term OSFED - Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder – which is actually the most prevalent diagnostic category, because eating disorders don’t fit into tidy boxes like we expect them to. They are complex and nuanced; there’s no one reason someone develops an eating disorder (and all the many reasons are way too long to go into here!) Atypical Anorexia can come under this category, which is anorexia but at a “healthy” weight or above. The issue here is what is deemed as “healthy” is based on a flawed BMI system, created for white European men only, so it has been recognised as not an accurate predictor of health. There are also biases and assumptions of medical professionals, plus the limited resources on offer for eating disorder treatment, which often results in the “sickest” people getting help (i.e. thinnest). It’s a reactionary system, based on restoring someone's weight, though of course as eating disorders are to do with mental health, having a “healthy” weight does not mean the person has recovered. The short version of this is, the entire system is broken and people are not getting the help they need. (No disrespect to anyone working in the NHS, you’re just trying your best and I thank you for that.) My focus is usually on the societal and cultural aspects of eating disorders and disordered eating. I use the term “disordered eating” as that includes people struggling with eating who don’t fit the diagnosis criteria too – of which there are a lot! I’ve worked for eating disorder charities for about 5 years now and I continue learning more every day. I’ve heard more and more stories over the years from people who are frustrated, unheard, not believed, passed off, sent to weight management services or Slimming World, and judged because they don’t fit what an eating disorder “should” look like. All of this is causing an incredible amount of harm, discouraging people from seeking help. Even writing this here, I’m concerned about creating more fear. Do we warn people of this and risk putting them off asking for help? Or is warning them needed so they can be prepared? If you’re reading this and you’re considering reaching out for help with an eating problem, please still do – there are good people out there who can help you. If you don’t find one initially, see someone else. If you’re at a higher weight, a focus on anything to do with intentional weight loss will NOT be helpful so do set boundaries around this. You can refuse to be weighed too, or if they say they need to, tell them you do not want to know it. I tell healthcare providers that I do not want to know my BMI every time I visit and they are fine about that. I used to feel awkward about setting those boundaries, but with practice I now definitely don’t! Boundaries are self-care! My work has led me to learn so much about people’s relationship with food, and to continue reflecting on my own. Everyone has a body, and everyone needs to eat, so it’s really important for professionals to consider their own relationship with food and their body. Sadly there is a lot of weight stigma, bias and discrimination in the medical world, in the therapy world, and…well, THE WORLD. Nobody is immune to weight stigma and fatphobia. When I talk about weight biases in the medical profession I don’t blame individuals but rather recognise that we’ve all grown up in a society that tells us thin is good and fat is bad. This is why unpacking and challenging weight stigma and fatphobia is so important. On an individual basis, the fear people hold about being fat is both deeply understandable and so saddening to me. There is no shame in holding these views, there is no shame in chaotic eating, or having tried every diet in the world, or having purged, and there is certainly no shame in having difficult emotions around food and your body. We live in a world where this is created and normalised.

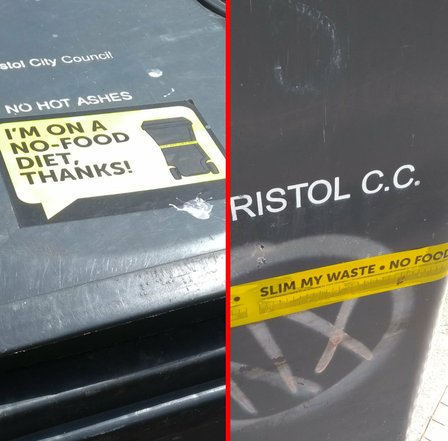

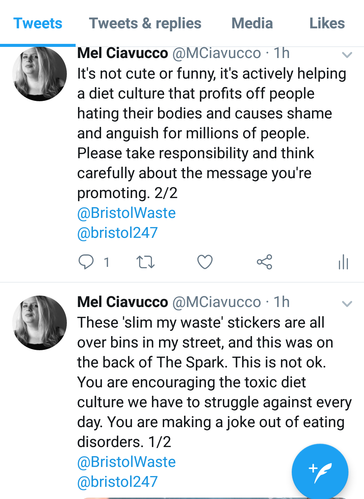

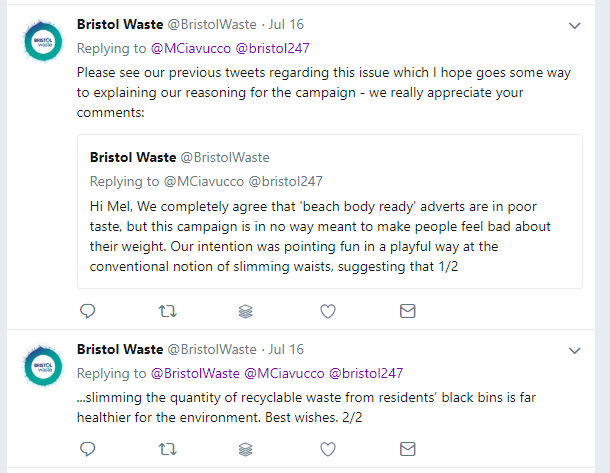

If you’re in a larger body and you’re embarrassed or ashamed that you just can’t seem to lose weight or keep it off, please know that this is not your fault. Many people’s bodies just aren’t naturally made to be thin, and the focus on thinness often drives disordered eating. Sadly, this focus on trying to do something which supposedly makes you “healthy” is likely the very thing negatively impacting your physical and mental health. The fear driven by narratives such as “the ob*sity epidemic” is very real and can make some people terrified that being fat will kill them. It will not; fat is not the killer but rather associated illnesses, plus the stress and trauma of living in a world that terrifies people into unhealthy behaviours such as yo-yo dieting, disordered eating, eating disorders, compulsive exercise, self-harm and more. This fear is not driving change, it’s only making things much, much worse. Fat is not an evil thing to be eradicated, but weight stigma, fatphobia and discrimination is extremely harmful and needs to stop. Many professionals will say that not all eating disorders are about body image and weight, which is true, however dieting is the biggest risk factor for an eating disorder. Dieting is often a result of wanting to lose weight to fit with the societal narrative of thinner equals healthier (not true), so it’s all rooted in weight stigma and fatphobia. Eating disorder professionals, medical professionals, therapists/counsellors, and other professionals working with anyone who may struggle with eating (which is A LOT of people) need to understand weight stigma and fatphobia for this reason. Many people are avoiding reaching out for help, being refused help, being wrongly diagnosed, and being judged for not being “thin enough” to have an eating disorder (sadly this is very common) so things need to change now. When I see statements like “eating disorders don’t discriminate” it makes me think about how eating disorders can often be seen as a disease that suddenly grips people, as if in a bubble from the rest of the world. Eating disorders are created from, and influenced by, a world full of inequality and discrimination. We cannot separate the person from the society and culture that has shaped them. The eating disorder treatment world is largely white, middle-class and able-bodied (professionals and researchers, and well as patients) which means this is the centred experience and everyone else is potentially left out. Also, recognising that fatphobia has roots in racism (see Sabrina Springs' work) and the impact of transphobia too, in the wider context of a capitalist system… the people who need help the most are sadly so often the ones being failed. Until we as a society can get our heads around the fact that most with people eating disorders are fat, AND that those people may also be black, trans, disabled, and/or a mix of identities, we will continue not to meet people’s needs. Saying “eating disorders don’t discriminate” is all well and good but sadly the systems designed to help and treat people often DO discriminate. I offer training for professionals on weight stigma and disordered eating, and I run Body Acceptance Workshops for people wanting to improve their body image. Find out more here. I am in the final stages of training as an Integrative Counsellor and I will be taking on clients in 2023. Please contact me to find out more. Bristol Waste are running a “slim my waste” campaign to encourage people to use separate food waste bins. On every wheelie bin, bright yellow stickers read “I’m on a no food diet” and tape measure style “slim my waste” stickers are wrapped around the middle section. A funny play on words? Not for the 1.6 million people affected by eating disorders in the UK. I’m all for food composting, but there must be better ways to do it than supporting toxic diet culture. In a world where one in four 7-year-old girls have tried to lose weight at least once, it’s imperative that companies promote themselves responsibly. It’s reported that 70% of women have felt pressure from TV and magazines to have the perfect body. And it’s not just girls - 60% of people say they feel ashamed of how they look. Imagine having to walk past a line of wheelie bins, all decorated with tape measures, and having the words “slim my waste” stuck in your mind for the rest of the day. After spotting a full page Bristol Waste advert on the back of The Spark (now run by Bristol 247) with the slogan “have you slimmed your waste yet?’ I decided to tweet Bristol Waste. Their reply suggested other people had flagged it up as an issue too, and this was a copy-and-paste response. What they're effectively saying is “that wasn’t what we intended” and dismissing it as a problem because they don't think it affects people. Well, it does. Multiple people are telling them this. It is arrogant, irresponsible and unprofessional to dismiss it.

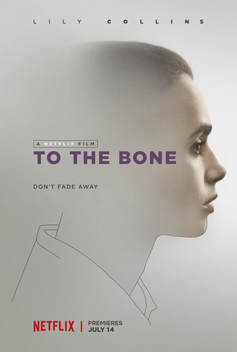

These bins are yet another thing people have to walk past every day demanding them to be thinner. Britain’s diet industry is worth billions of pounds - they profit off making people feel ashamed of their bodies. They tell us that beauty and health means being thin, which is simply not true. Healthy bodies come in all shapes and sizes. The diet industry need us to hate our bodies and aspire to be ‘perfect’ otherwise they wouldn’t make any money. “Being sold the message of dieting can produce drastic dieting which can lead to eating disorders. Getting rid of dieting could wipe out at least 70% of eating disorders.” Dr Adrienne Key, Royal College of Psychiatrists. Many people live with guilt and shame around food every day. Many struggle to feel worthy as a person because they’re not thin. They’re bombarded with digitally altered images, Slimming World leaflets through their front doors, adverts for gym memberships and diet pills, the voices of bullies on the street or on the bus. Every time they walk past one of these wheelie bins they’ll be reminded of how they’re not good enough. Bristol Waste is only a tiny part of this bigger cultural problem, but that doesn’t mean they can’t do something about it. To say these slogans are just a bit of fun is to completely deny somebody else’s struggle. It’s never just a funny play on words. Slimming world use “syns” to describe treat foods because they know, psychologically, it won’t make any difference how the word is spelled. The word has the same effect in the mind - guilt and shame - the very thing that brings them more money. I appreciate that Bristol Waste are trying to help us recycle and help save the environment. The funny face stickers for the food waste bins are fun and a great idea. However, the unwillingness to recognize the potential damage of the “slim my waist” stickers shows a complete lack of empathy towards another (large) group of people’s perspective. To deny the problem is to sit in a position of privilege and say “well, it doesn’t affect me”. Positive body image is integral to emotional and mental well-being and it’s crucial that companies and advertisers think carefully and take responsibility for their actions to help make a positive change for the future.  Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. Content warning: eating disorders To The Bone is somehow listed as a 'comedy drama' on IMDB. It's certainly not a comedy. Writer/director Marti Noxon was apparently influenced by her own eating disorder experiences and wanted to help raise awareness of the illness. Whether it does this in the right way is up for debate, and I’m still not entirely sure myself. As much as I’ve had a very weird relationship with food and a rather negative relationship with my body in general, but I’ve not had anorexia so it’s not fair for me to question if the film portrays it well. Though of course it’s also subjective, so To The Bone may have been Noxon’s experience of anorexia but other people may have a very different reality of it. Writing about mental health is tricky, especially for films. From my own experience of learning to write screenplays, it’s all about the three act structure and there’s an expectation to resolve all issues in the final act. This might be something relatively easy to do in a blockbuster action film (there's usually just a big fight and then the guy gets the hot girl) but when there are characters with complex mental health issues it’s hard to realistically resolve these in such a short time. In real life, unpicking trauma can take years. This, for me, was where To The Bone went wrong. There was a lot of focus on the illness (which is always risky as it can end up being a "how to" of eating disorders) and the recovery seemed to be done by way of a rather strange, quite rushed, epiphany sequence. And of course there was a boy involved too…uh oh…. There are only two notable male characters in this film and they hardly speak to each other. Technically you could say it passes the Bechdel test with flying colours. The Bechdel test asks if two women talk to each other about something other than a man, and although this was originally a useful test, it doesn’t stop women being overruled by men in films. In To The Bone, both men talk to her like crap, and their behaviour is never justified as such. It’s a particular gripe of mine when women are saved by men in films, but especially when it involves a mental illness. Often there just is no cure, another reason why it’s so hard to make a film which tells these stories in a satisfying, believable, responsible way. My first screenplay was about a young woman with depression and anxiety, and I’ve spent so long working on the ending to find that balance of it being hopeful but realistic. There are many ways people cope with having a mental illness but meeting someone and falling in love is often not the solution. This only puts pressure on another person to have to ‘fix’ them. Strength comes from inside yourself, not from Prince Charming. This is obviously why I don't write romance! Lilly Collins, who plays Ellen in To The Bone, apparently had an eating disorder herself. It’s no surprise then that she was brilliant in the role, but she did lose weight for it. We can’t say this was a bad choice on her part, because she’s a grown women and is responsible for her own body, but there’s no denying it was a risky move which might have potentially triggered her ED (eating disorder) again. Whilst we’re on the topic of triggers, the film does have calorie counting, weight loss tricks, disordered eating etc, and there are triggering images. We can’t tell people with ED not to watch this film, it’s their choice and many of them will choose to because it’s relevant to them. As with 13 Reasons Why, all Netflix can do is make sure their audience is warned about the content, otherwise the responsibility lies with the audience. We also can’t say these kinds of films and TV shows shouldn’t be made, because otherwise how would we start a dialogue around them? If this film was banned, where would the line be drawn when it comes to other films? On the other hand, there are dangerous images of thin women everywhere. For someone to play an anorexic woman in a film, she needs to be noticeably thinner than other women in films, and the ‘normal’ level is pretty bloody thin. It’s not hard to find ‘thinspiration’ in this world. Some people with anorexia might want to be triggered. You only need to step into the world of ‘pro-ana’ (pro anorexia) websites and thinspiration (sometimes called ‘thinspo’, or even ‘bonespo’) to see that being triggered can be a good thing for them. Ultimately there might be a horrible irony to Lilly Collin’s choice to lose weight for the role in that she may become an unintentional thinspo idol. In short, maybe this film is made for people who don’t know very much about eating disorders. There could be many benefits to parents or teachers, for instance, watching this to help recognise some things that people with anorexia may do. In this sense of raising awareness, maybe it works.  Look, it's Keanu Reeves. Look, it's Keanu Reeves. But let’s talk about Keanu Reeves. Keanu fucking Reeves. Personally, I think he has the screen presence of a lamppost. Apart from in the Bill and Ted films of course. (#NotAllKeanuReevesFilms) But maybe it’s not all his fault in To The Bone. It’s a mix of: a) the annoyingly privileged setting (they clearly got her into that residence ‘cos they’re loaded) b) patriarchal bullshit c) therapists always* being shit in films *Okay, so therapists in films are not all shit (#NotAllTherapists) but they need to be recognised in the script as being shit if they are. Take, for example, Robin Williams in Good Will Hunting. He’s not set up to automatically be the one we should trust because he’s working through his own issues. This works. What doesn’t work is when you get a weird, creepy therapist like Keanu Reeve’s character in To The Bone, who is treated like some kind of cult leader. His behaviour is then validated at the end when she returns to the house, and we’re supposed to believe that it’s a positive outcome for her. It’s great that she chooses to take steps towards her recovery, but to go back to a place run by such a weird creepy bloke is simply bonkers. Keanu/doctor/therapist/perv/cult leader is seen as radical because he says the word ‘fuck’ a few times. ‘Tell those negative thoughts to fuck off’ he says. So insightful and professional. Then he basically tells her to grow up and get over it, she goes away and has her little epiphany and then realises he’s right. The guy who thinks he can cure eating disorders by taking them to dance in some fake rain, is ‘right’ all along. She should’ve reported him, or at least gone to another clinic. But then, the boy was there. Prince Charming. The pompous British twat who came on to her but then instantly body shamed her when she said no. The one who tried to force-feed her chocolate. The one who sat on a tree branch in her epiphany dream – the bit where she was dressed up like some kind of born again Christian angel virgin and he made everything all better by telling her she was pretty. Couldn’t the stepsister have been sitting on that branch with her, Ellen wearing her usual clothes? Can she not take steps to recovery without there being a man there to help, and without having to wear less eyeliner? Then there was the mother and the moon. That strange, inappropriate feeding bit where her mother cradled her like a baby. I can see the theory behind that and it was nice to have a slight resolution to their seemingly turbulent relationship, but…really? And the moon…God knows. For a character who didn’t seem remotely spiritual, this ending was a little bit of a stretch for me. But the point is, she reaches the stage where she decides to follow the path to recovery. The intentions are good overall, and above all it’s a dialogue opener. The strength of the film was certainly in it’s strong female characters and family dynamic, showing how eating disorders effect the whole family. I hope this movie helps people learn a little more about an under-represented topic in film and will open conversations about eating disorders and how we can help people and families affected. If you or someone you know is affected by an eating disorder, here are some recommended websites: https://firststepsed.co.uk/firststepsed.co.uk/ https://www.b-eat.co.uk/ A note about triggering FEELING TRIGGERED IS NOT A WEAKNESS. If you’re the sort of person who mocks people for being triggered by things they watch or read, or uses the term ‘snowflakes’, you need to take a serious look at what kind of person you are. You wouldn’t laugh if that person was a relapsed drug addict, or if somebody had an injury which flared up. It proves how we don’t take mental health seriously enough as a society. Many people have had difficult experiences in their lives which can be easily triggered, bringing up difficult emotions. If you’re lucky enough not to have this problem then please recognise that not everyone is the same. It is not cool to laugh at somebody who is upset about something. It shows a lack of empathy, and that frankly you’re just a d*ck. Be excellent to each other! |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|