|

A couple of years ago I wrote an initial reflection on working with perpetrators of domestic abuse when I was relatively new to the work. Since then, sadly the service has closed as the funding ended. This is not uncommon in this field; victim services are barely funded enough so perpetrator services can be a hard sell. So, given this sad ending, I wanted to reflect on this amazing work and what I’ve learned about working with perpetrators, and about what we need to do as a society to help men. Due to the nature of this work, no names or identifying information about the organisation or individual involved will be used. I’m a counsellor in private practice but I worked three days per week for a domestic abuse charity, doing group and 1:1 work on a perpetrator programme. I started as a group facilitator and then I got more involved, doing assessments and also doing one-to-one Behaviour Change sessions. I was surprised that I could even do this work, I’d always been drawn to it but thought I was just being naïve at first! I remember when I first started training to be a counsellor, we were asked if there were any clients we wouldn’t want to work with. Some of my peers said offenders/perpetrators (especially those who had harmed children) and as much as I respected their choice, I became aware that I was one of the few who particularly wanted to work with these groups. They are the most stigmatized and shamed, and who arguably may need us the most. I knew if I could get into this work somehow, I definitely should. It felt so important. I thought the concept of perpetrator programmes was great; as well as helping people leave abusive relationships, we had an opportunity to go to the root of the problem and help break the cycle. It feels like our domestic abuse victim services are just firefighting at times, doing the very best they can do with the funding and resources available. Domestic abuse is about patterns of power and control, so when an abusive relationship ends, there’s always a risk that either person could enter into another abusive relationship. These are generational cycles which many people don't realise that they're in. I wanted to help break the cycles and help the ripple effect, ultimately to help partners, future partners, children and grandchildren be safer too. My first observation of a perpetrator group was eye-opening. I was struck by the level of openness and honesty from the group members. I also admired the challenges offered by the facilitators, whilst holding a non-judgmental and compassionate space. I knew it was for me instantly. I was worried I might be scared and would want to literally run out of the room, but something in me just felt right. For somebody who was a timid child being told by many to “be more assertive”, I surprised myself by becoming a confident, challenging facilitator! The most important part of this work was the support from the team. My co-workers, supervisor and manager made this possible; it’s crucial to have a good team to be able to “hold” this work and manage risk. I’ve always been fascinated by why people do what they do. I don’t believe that people are just “bad” or are born “evil” or “monsters”, it’s just not possible. People who hurt others have often been hurt themselves. They may have had difficult relationships, or sometimes struggle to have meaningful relationships at all. There can be attachment and child development issues, past abuse and trauma. The complexities and nuances of what makes a person harm others are complicated and different person-to-person, but everyone deserves the chance to be heard and shown respect and compassion. The perpetrator programme offered this balance of being challenged and held accountable, whilst being strengths-based, compassionate and empathic. Many perpetrator programmes are just for cis-gendered men, but this doesn’t mean other people aren’t abusive of course. There needs to be more provision for programmes for a range of genders, sexualities and relationship arrangements. However, there is barely enough for men at the moment, and men are the most common perpetrators of abuse. This can be a confronting thing to talk about, especially online, as there can be backlash, defensiveness and “what-about-ery”, e.g. “but what about all the men who are abused?” This is a valid point, but can often be used to derail the conversation about male violence. We need to name it to help solve the problem. In my view, patriarchal norms and expectations harm everyone. As a woman, I feel I was socialised to adhere to the male gaze, meaning I needed to try my best to be attractive to men and give them what they wanted. My self-worth was wrapped up in what men thought of me. I gave their opinion more worth than my own, about my own body! These messages came to me from films, TV, family, friends…it was the water I swam in so I never questioned it. It was just normal. When I started learning about feminism later, I had a lot of unpacking to do. I realised that I upheld unrealistic standards of myself, but also, I was helping uphold masculinity standards too. Masculinity comes with its expectations, norms and demands. On the programme we would explore the “man box”, all the things that keep men trapped in the expectations of their gender, and the consequences for stepping outside the box. The pressures and expectations can include, not being “emotional”, not crying, being tall and muscular, being “the provider”, not showing vulnerability etc. Sadly, this meant the men often had learnt to push down their emotions, as they were unacceptable. Many had never learnt how to talk about emotions and never had that modelled for them. Part of the magic of group work is having the space to talk to each other, which in turn helps model vulnerability and provides practice in communicating about emotions. It’s an experiential, powerful intervention, as well as the psychoeducation, exercises and discussion on the programme. These together, the relational group dynamics and the programme topics and themes each session, created an intense but very impactful intervention. It felt like such a gift and a privilege to do this work and witness this. As facilitators, our strength is in being compassionate but challenging. Trying to hold somebody accountable by making them feel belittled or told off is just not going to work. It triggers the shame that so many of these men have deep down, that is so hard to let out, let alone speak about. Their shame can feel too much, so it’s often the cause of defensive behaviours. When you’re not used to being vulnerable, it can feel terrifying. We needed to help hold this shame whilst they explored and worked on themselves and their behaviours. We often talked about the “pit of shit” (was “shame” but “shit” became more fun), and how getting out of it required them to clamber out onto the path of accountability. But it’s hard to climb out whilst stuck in the sticky, muddy shame, especially for those with low confidence and self-esteem. It brings a paradox for some who would consider these men not to be deserving of feeling better about themselves, but this is the very thing needed to climb out of the pit and take responsibility. We loved an iceberg on the programme. We’d draw the angry behaviours at the top (i.e. what you can see, e.g. shouting, slamming doors), with the underlying emotions below the surface, e.g. fear, vulnerability, shame. A theme I often noticed was jealousy. This often linked with underlying feelings of insecurity and low self-esteem. The controlling behaviours stemmed from the jealously and inadequacy, and fear of abandonment. This could have been impacted by experiences in previous relationships and likely caregiver relationships in early childhood. An insecure attachment can be a common factor with some men on these programmes, in my experience. Entitlement, in the context of being entitled to women’s bodies, may be more likely to stem from societal and cultural influences which tell men they have a right to women’s bodies. We see this a lot in the “manosphere” (men’s rights activists, incels etc) which many might argue is getting worse now we are in the “Andrew Tate era”. It seems the idea of being an “alpha” is becoming important again (which to me is men literally putting themselves in the constraints of the man box), and with this comes the idea of power over women (and other men). Ultimately, I believe so much of this is rooted in fear of losing power. Women and trans/non-binary people are taking up more space now and having more power, and this is seen as a threat to men. It’s not of course, it’s an opportunity for us to dismantle patriarchal and traditional gender norms and expectations, which would help us all. What it means to be “masculine” needs more flexibility and more empathy. We need positive male role models who can help other men, standing against harmful behaviour but in a way that doesn’t shame them. We need media literacy for children and young people to help understand and reduce the risk of online grooming into the “manosphere” and ethical use of pornography. We need women to stop upholding gender expectations on men too and support them to be able to feel safe to show emotions. We need to stop the increasing transphobia and make it safe for people to be themselves. We need better representation of vulnerable men on TV and in films. We need to stop normalising abusive and controlling behaviours in the media. We, as a society, have a lot of work to do. But we also need to have compassion and remember the humanity in people, and believe that some people are absolutely able to change. I’ve seen these changes happen; men have become better fathers, they’re able to understand themselves and their behaviours so much better, and they now model to their kids that it’s OK to be vulnerable, and how to take accountability. We need to keep breaking these cycles for generations to come. I did a talk with Online Events about this too, if you’d like to find out more or purchase a recording CLICK HERE. I also offer other workshops, please check out my workshops page for what’s coming up.

0 Comments

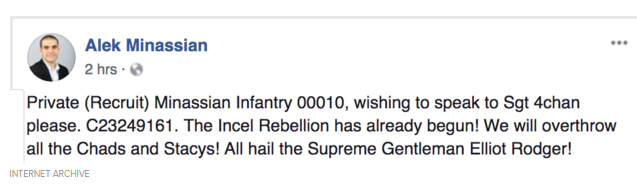

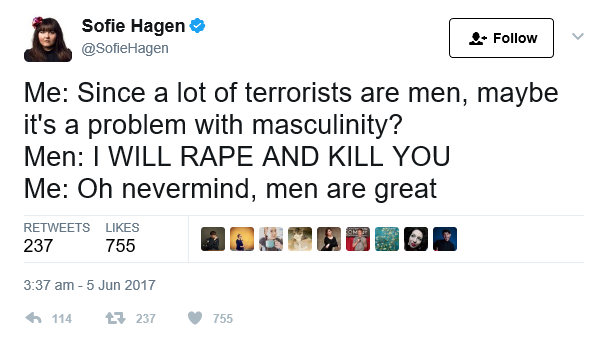

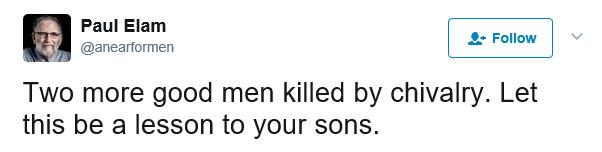

Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. TW: Domestic violence and abuse.. The world is football crazy at the moment. I hate football. The other day I was scrolling through Facebook when I saw this… Although the study was only conducted in Lancashire, it wouldn’t surprise me if it’s a snapshot of a problem throughout the whole country. “Incidents of domestic abuse rose by 38 per cent in Lancashire when the England team played and lost and increased by 26 per cent when the England national team played and won or drew compared with days when there was no England match. There was also a carry-over effect, with incidents of domestic abuse 11% higher the day after an England match.” – Lancaster University Here in the UK, we know and accept the actions that come along with football: binge drinking, fighting, chanting, and general obnoxious behaviour. Say “it’s just a game” to someone and you’re in danger of getting your head kicked in. So what makes this aggressive behaviour in football so prevalent? I used to live with some guys who were really into football. It was the first World Cup I’d been involved with, ‘involved’ meaning I didn’t care about the game but I was there for the booze. When England lost, my male friends were fuming. My female friends were disappointed, but my male friends were big balls of rage ready to explode. When we got home, one of them started punching a wall. We dragged him away and calmed him down, and then he started crying. It was like years’ worth of emotion all burst out of once. Looking back now, I see this is so much deeper. I used to question this particular friend a lot when it came to emotion and football. I used to tease him with the whole “it’s just a game” thing but sometimes I was worried he might actually punch me. He said football was the only time he cried. It was the only time it was allowed; it was pathetic for men to cry about anything else. I thought this was the pathetic concept and would take the piss out of him for crying over some guys kicking a ball around. But now I realise, when that’s the only thing you’re allowed to be emotional about, no wonder its important. Men’s Rights Activists are quick to point out that domestic violence victims can be male too, yet they often use this to derail arguments and take feminists down. They don’t seem to see that patriarchal rules and gender expectations have screwed us all over. Little boys are given toy guns and told to be strong. They see their favourite action film stars looking muscly and buff and quickly learn that being a man is about looking physically strong as well as acting strong. The world teaches boys that being kind and having empathy is weak and girly, and that emotions should be ignored, instead of teaching them how to feel and deal with them. So when a game comes along where all this pent-up emotion is allowed to come out (helped by a lot of beer) it literally will burst out. Little girls have masses of expectations put on them in terms being pretty and growing up to meet the harsh expectations of society, but at least we were allowed to cry. Domestic violence numbers are hard to quantify as many cases go unreported due to fear of speaking out. Any person of any gender can be a victim of domestic violence, but in the UK generally the majority are women. “In 2013-15, four times more women than men were killed by their partner/ex-partner” - Office for National Statistics (2016) Compendium – Homicide (average taken over 10 years) “Women experience domestic violence with much more intensity – 89% of people who experience four or more incidents of domestic violence are women” - Walby and Allen (2004) Domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking: Findings from the British Crime Survey It’s hard to use the term ‘toxic masculinity’ without seeming like I hate men. I don’t want to place any blame on men, or football. I want to question why, get to the root of the problem, and take steps towards positive solutions. We can’t just blame football and binge drinking, we have to examine our entire culture and the way we expect boys and girls to behave. We live in a world where people seem to believe gender fits neatly into two boxes and we have dress in a suitable way to prove which box we’re in so other people feel comfortable. People have difficulties understanding non-binary people – they feel the need to assess if they’re ‘really’ a man or a woman underneath. Does having a penis make somebody a man? Does fitting into your stereotypical view of masculinity make them a man? And why do you need to know so badly? It we really treated everybody equally, you wouldn’t need to know what kind of genitalia a person has in order to be able to talk to them like a human being. Football doesn’t turn somebody into a domestic violence perpetrator, but if they have a tendency to be aggressive, it might push them over the edge. We also have to remember that domestic violence isn’t always physical. There is emotional abuse (manipulation, coercive behaviour etc.), financial abuse and verbal abuse. It’s about control, which is why domestic violence is a feminist issue. The reason why I talk in terms of violent men towards women is because this is the most common, although abusive relationships can be between anyone of any gender. Living in a patriarchal society where men have the most power means we’ve all grown up seeing heterosexuality as the norm and male dominance as acceptable. In the media, they often depict domestic violence as a man with balled up fists and a woman cowering. It’s similar to how rapists are traditionally thought of as perverts who linger in dark alleys waiting for a young random girl to pounce on. This is not always the case. In both these instances, the man can often be someone the victim knows and loves. This view of the stereotypical ‘bad man’ often results in women being doubted when they come forward about rape, sexual abuse or domestic violence if the perpetrator doesn’t fit that stereotype. I once saw a couple arguing outside a pub with their three children watching. The man slammed her up against her car and was shouting in her face. The kids seemed surprisingly relaxed, like they’d seen it all before. I rang the police and reported the incident. There was a local shopkeeper who had been standing outside watching it all. I told him the police were coming and he shook his head at me. He told me I shouldn’t have called the police, it was no business of theirs. He said it was a family matter for them to sort out themselves. I was so saddened by his lack of care, but was well aware that his view would be a popular one with many people. Power dynamics in relationships are very complex. We’re influenced by our own identities, the expectations placed on us by our family and friends, and the pressure in the media to be attractive. Then when we're not happy all the time we’re sold the magic pill to make it happen. Many of us are not taught how to talk about emotions in relationships. Our society tells us a failed marriage is shameful, yet if we have a long-term job and moved on we’d put it on our CV and would be proud of it. “Happily ever after” is a lot of pressure. Relationships are hard and we all need a little help sometimes. Communication problems are the biggest issue I’ve seen working for a relationship counselling organisation for over five years. On my journey further into the body positivity world, I’ve joined a lot of Facebook groups. Many of the people are women and are married with children. Some of them have posted some appalling things their husbands have said to them: he doesn’t find her attractive anymore since the “baby weight stayed on” and saying she needs to “tone up a bit”. There were examples of men not supporting their wives when somebody else says something unacceptable about their weight. Many women excuse this behaviour by saying things like “he probably didn’t mean it like that”, “he doesn’t say this kind of stuff all the time”, “he was just in a bad mood”, “he was drunk”. In a similar way after a football game there may be the same excuses: “he was just upset because his team didn’t win”, “he was drunk”, “he’s not normally like this” and the saddest one “he’ll change”. Some people wonder why women stay with men who treat them this badly. I’m guessing many of these people have been lucky; they’ve maybe never been involved in any kind of domestic violence situation themselves and don’t understand the complexity of problems around controlling relationships. This view – of “why doesn’t she just leave?” places the focus on the woman having to do something about it, instead of challenging the behaviour of the man. This is also known as victim blaming. For me, being overweight meant that I always had to be on a diet because I thought I would only get a man if I was thin. When I didn’t lose weight, I realised I would have to settle for any guy who showed any interest - he would be the best I could get. Nobody else would ever like me, so I’d have to do whatever it takes to keep him. Many women stay with men who treat them badly for this reason – they’re scared they’ll never find anyone else and are terrified of being alone because society has told them they’re not good enough. Some women are also scared to leave in case their partner physically hurts them. Other women are bribed into staying because the man has control of their bank account. Many women feel it’s their own fault and think they deserve to be treated this way. There are literally millions of cases and reasons, often tied into complex mental health difficulties too. So next time you think about saying “she can do better” or “she should just leave” then please think again. These women don’t need to change, the culture needs to change. Our relationship ideals are strict and unrealistic, mainly from the impact of fairy tales and more recently, films. The message is: find “the one”, settle down and then be happy forever. The Fifty Shades saga is meant to be a bit of kinky fun but in fact is about a relationship involving two very messed up people - a young naive woman and an older, controlling, privileged, coercive man. These films are released on Valentine’s Day and celebrated as romantic. Everyone swoons over the alpha male, who seems to be a psychotic stalker. These films make light of terrible behaviour. It tells women that putting up with bad behaviour will pay off. This is another reason why women stay in abusive relationships, because they don’t realise it’s abusive – the bad behaviour has been normalised in our society. Domestic violence is a huge cultural problem which we can only hope to start chipping away at by teaching young people that it’s okay to be different. That they’re just as important as everyone else no matter what their shape, size, gender, sexuality or skin colour. It’s okay for people not to fit into the mould of being a boy or girl, it’s okay for boys to cry, and it’s okay to ask for help. We can’t pretend that emotions don’t exist – we’re human, we all have them. We need to be equipped with the tools when we’re younger to know how to deal with our emotions so that it doesn’t get stored up and come bursting out because of a football game. Freephone 24-Hour National Domestic Violence Helpline: 0808 2000 247 - Refuge TIGER (Teaching Individuals Gender Equality and Respect) For Relationship help: https://www.relate.org.uk/relationship-help Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. On Monday 23 April, a man drove a van into a group of pedestrians in Toronto, killing 10 people and injuring 13 more. It later arose that this man was a self-proclaimed ‘incel’ having posted on social media just before the attack: ‘Chads’ and ‘Stacys’ refer to sexually active men and women. The attacker explained his angst in a video he made before the attack where he talked about still being a virgin and vowed to kill women for rejecting him. What is an incel?‘Incel’ is short for ‘involuntary celibate’ - they’re part of the Men’s Rights Activist (MRA) movement. The ‘manosphere’ is another name for the huge dark corner of the web filled with different factions of these misogynistic men. Although I’ve spent longer than I should’ve in the manosphere, even I don’t understand the crazy hierarchy of men’s rights activists, pick-up artists, incels and numerous other groups and divisions within the movement. It’s a scary part of the internet to venture, full of hatred and bitterness. Incels are predominantly straight white men who believe they’re entitled to sex. These men have little to no sex, unsuprisingly. They embrace their own helplessness at not being able to attract women and blame it on not being as attractive as the ‘chads’. They embody being the victim and become incredibly bitter towards the men who can get women, and the women who sleep with them. Why are incels like this? There are a lot of people on Twitter at the moment talking about how incels are terrible people, which is fair. However, I’m interested in why they act the way they do because this might help us learn something so we can help. Also, I’m aware that these men are very angry. Directing more anger and hate at them will only prove them right: they’re the victims and everyone is against them. They’re already angry because women won’t have sex with them, because other men are more attractive than them and because other people in society are gaining more power than them. All their actions are fear driven. Despite them playing the part of strong men, they’re often lonely and vulnerable. Dating is hard. There are lots of men who can’t get dates easily, but it’s not down to their appearance. It’s likely the bitter attitude of most incels that repels women. They’re in a vicious circle: not able to get women because of their attitude, but the rejection/fear of trying in the first place/having been hurt in the past, perpetuates that bitter attitude. Women are taking control of their own sex lives and patriarchal traditions are being dismantled. We are trying to give power to people who have never had it before - trying to give people a voice. These men have grown up thinking the straight white man is at the top – they rule the world. They are scared that giving power to another group means taking it from them. Again, it’s all rooted in fear. So incels are lonely men, sitting behind their computers complaining about how they’re not attractive enough to get women. When I think about this I see low self-esteem, low confidence and low self-worth. Many of these men may hang out online because they have social anxiety problems. Ultimately, anybody who goes around telling everyone they can’t get laid, is asking for help. They’re just asking for help in the wrong places. If many of these men have social anxieties or mental health issues it might be a daunting prospect to ask for help offline. They may not even have many friends. It makes sense that online forums are the ideal place to meet people in these circumstances. Unfortunately, these can be full of like-minded incels or MRAs encouraging each other’s hatred and anger. What these men are really looking for is a community, a support network and ultimately some help. How can we help incels?You may be thinking “no way, I don’t want to help these guys” but how can we try to make a difference if we simply throw hate back at them? We could create a future that helps bring young boys into a world where they can ask for help without being sucked into a potentially dangerous community. It’s not the old school MRA’s or incels that will drive vans into people or pick up a gun and storm into a school, it’ll be the younger ones or the more vulnerable men that do. Forums are a world where suddenly people understand them. I wrote a short story about this a few years ago called Manosphere, about a teenager - bitter about his ex-girlfriend - who turns to violence. I wrote it to demonstrate how easy it would be for someone desperate for help to get led down the wrong path. It was fiction but it this kind of thing now keeps happening in real life. Some incels are clearly experiencing anxieties they don’t know how to cope with alone, and violence - to themselves or others - is their only way out. What if they were able to ask for help in “real life” not online? What if men weren’t taught that women are sexual objects? What if they weren’t told to “man up” and they weren’t given toy guns to play with as kids? Children are constantly learning and all these things all have an impact. When men are taught from a young age that women are there just for their sexual gratification, and that they rightfully own the power, it’s no surprise that these expectations are not going to be reached. The irony behind the MRA movement is their major concerns over the high male suicide rates and lack of support for men’s mental health. MRAs are arch rivals of feminists, yet ironically they often want the same thing. If incels felt they were able to access support from a healthy, safe place, there could be a chance they could get the help they need. Difficulty forming relationships can be because of many problems in the past: they might’ve been hurt by girlfriend, or women in their family, or maybe they’ve been bullied because of their appearance at school. The way to unpick all of this is with a good therapist. It could be that some of these men have tried to access therapeutic services but they’re too expensive or the waiting lists are too long. This is why mental health needs to be a priority. It’s just as important as physical health.  We need to be teaching young boys not to channel their emotions as anger, but rather that it’s okay to show emotion and empathy - it’s not a sign of weakness. Gender equality is about not teaching girls to be princesses and not teaching boys that crying is weak – it ultimately helps everyone. Thanks for reading. Sending love to all affected by the Toronto tragedy. Let’s try to make the world a kinder place.  Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. One of my favourite podcasts is The Guilty Feminist. Deborah Francis White is such a hero and I really admire her attitude and assertiveness. I never understood what assertiveness was when I was younger but Deborah Francis White is a pure vision of it. In The Guilty Feminist podcast episode about strengths and weaknesses, her challenge was to do one minute of automatic writing (also called freewriting) about strengths and weaknesses. I decided to give it a go but fully expected to mostly write about the pizza I was making for dinner. I did just the strengths as I often put too much emphasis on my weaknesses. I struggle with my inner critic and I think it would be counter-productive to fuel that right now. To put this in context, I’ll need to explain something that happened today. I’ve been having EFT sessions, that stands for Emotional Freedom Technique. It’s like a mixture of acupuncture and counselling (sounds weird, I know). You talk through a problem to find a statement and then you tap on points on your body whilst repeating that statement. For example, "even though I’m worried about shitting myself on public transport, I trust that I will be fine" (that was an actual one I used, no joke). In today’s session, we focused on a statement about self-worth which brought out a very emotional response in me. When I’ve had counselling in the past I’ve even struggled to say statements like “I’m okay” because of how ingrained my self-esteem issues are. This is why I wanted to do the freewriting exercise just on strengths, to try and bring forward some of that self-love and confidence. I typed this in the same way I wrote it – trying to hardly let my pen leave the paper! So apologies for the sporadic punctuation but I wanted to avoid changing it at all. I’ll admit I got carried away and went slightly over one minute, but I didn’t want to disrupt the flow. So I’m doing my free writing so it’s going to be messy with no punctuation it’s about strengths my strengths are my ability to cook pizza dammit I said I wouldn’t mention pizza but sure it’s a strength it’s the Italian side of me wanting to feed people and make people happy. Other strengths I have are kindness which is important in a world really lacking in empathy and also I’m genuine and honest there’s too much bullshit in the world with people doing stuff because they think they have to fit in. My differences set me apart from everybody else trying to conform, another strength is my willingness to tackle things I’m afraid of for example escalators and boats despite the anxiety it causes also another strength is being able to cope as I’m more resilient than I think I always think I won’t cope but I always do. I’m glad I tried this exercise. I agree with what I wrote, but it’s always hard to say these things about myself because I’ve always been so worried about coming across as arrogant. Do as many men worry about this? I'm not so sure. Sometimes I find much harder to believe the positive thoughts than the critical ones. With practice I hope I’ll continue to try and appreciate my strengths, but it takes a long time to unlearn all these ideas about myself. However, there’s no point in wasting my life giving myself a hard time, I've got a life to fill with wonderful experiences! I don’t want to come across as a narcissist by sharing all these thoughts, I just hope that my experiences might resonate with people. I know what it’s like to find it easier to hate yourself rather than love yourself, and I hope that by supporting each other we can change this. I recommend trying this exercise, so grab a piece of paper and a pen and write for one minute, but if you get in the flow just keep going! You might learn something about yourself, or worst case it might just end up being funny. Win win. The Guilty Feminist had been a huge influence on me. It has helped me realise that other people have been through some of the same experiences as me and that it’s okay to speak up. I will no longer apologise all the time just because of my gender. Thank you to The Guilty Feminist podcast and to Deborah Francis White for being a source of inspiration, confidence, solidarity and wisdom.  Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. Content warning: eating disorders To The Bone is somehow listed as a 'comedy drama' on IMDB. It's certainly not a comedy. Writer/director Marti Noxon was apparently influenced by her own eating disorder experiences and wanted to help raise awareness of the illness. Whether it does this in the right way is up for debate, and I’m still not entirely sure myself. As much as I’ve had a very weird relationship with food and a rather negative relationship with my body in general, but I’ve not had anorexia so it’s not fair for me to question if the film portrays it well. Though of course it’s also subjective, so To The Bone may have been Noxon’s experience of anorexia but other people may have a very different reality of it. Writing about mental health is tricky, especially for films. From my own experience of learning to write screenplays, it’s all about the three act structure and there’s an expectation to resolve all issues in the final act. This might be something relatively easy to do in a blockbuster action film (there's usually just a big fight and then the guy gets the hot girl) but when there are characters with complex mental health issues it’s hard to realistically resolve these in such a short time. In real life, unpicking trauma can take years. This, for me, was where To The Bone went wrong. There was a lot of focus on the illness (which is always risky as it can end up being a "how to" of eating disorders) and the recovery seemed to be done by way of a rather strange, quite rushed, epiphany sequence. And of course there was a boy involved too…uh oh…. There are only two notable male characters in this film and they hardly speak to each other. Technically you could say it passes the Bechdel test with flying colours. The Bechdel test asks if two women talk to each other about something other than a man, and although this was originally a useful test, it doesn’t stop women being overruled by men in films. In To The Bone, both men talk to her like crap, and their behaviour is never justified as such. It’s a particular gripe of mine when women are saved by men in films, but especially when it involves a mental illness. Often there just is no cure, another reason why it’s so hard to make a film which tells these stories in a satisfying, believable, responsible way. My first screenplay was about a young woman with depression and anxiety, and I’ve spent so long working on the ending to find that balance of it being hopeful but realistic. There are many ways people cope with having a mental illness but meeting someone and falling in love is often not the solution. This only puts pressure on another person to have to ‘fix’ them. Strength comes from inside yourself, not from Prince Charming. This is obviously why I don't write romance! Lilly Collins, who plays Ellen in To The Bone, apparently had an eating disorder herself. It’s no surprise then that she was brilliant in the role, but she did lose weight for it. We can’t say this was a bad choice on her part, because she’s a grown women and is responsible for her own body, but there’s no denying it was a risky move which might have potentially triggered her ED (eating disorder) again. Whilst we’re on the topic of triggers, the film does have calorie counting, weight loss tricks, disordered eating etc, and there are triggering images. We can’t tell people with ED not to watch this film, it’s their choice and many of them will choose to because it’s relevant to them. As with 13 Reasons Why, all Netflix can do is make sure their audience is warned about the content, otherwise the responsibility lies with the audience. We also can’t say these kinds of films and TV shows shouldn’t be made, because otherwise how would we start a dialogue around them? If this film was banned, where would the line be drawn when it comes to other films? On the other hand, there are dangerous images of thin women everywhere. For someone to play an anorexic woman in a film, she needs to be noticeably thinner than other women in films, and the ‘normal’ level is pretty bloody thin. It’s not hard to find ‘thinspiration’ in this world. Some people with anorexia might want to be triggered. You only need to step into the world of ‘pro-ana’ (pro anorexia) websites and thinspiration (sometimes called ‘thinspo’, or even ‘bonespo’) to see that being triggered can be a good thing for them. Ultimately there might be a horrible irony to Lilly Collin’s choice to lose weight for the role in that she may become an unintentional thinspo idol. In short, maybe this film is made for people who don’t know very much about eating disorders. There could be many benefits to parents or teachers, for instance, watching this to help recognise some things that people with anorexia may do. In this sense of raising awareness, maybe it works.  Look, it's Keanu Reeves. Look, it's Keanu Reeves. But let’s talk about Keanu Reeves. Keanu fucking Reeves. Personally, I think he has the screen presence of a lamppost. Apart from in the Bill and Ted films of course. (#NotAllKeanuReevesFilms) But maybe it’s not all his fault in To The Bone. It’s a mix of: a) the annoyingly privileged setting (they clearly got her into that residence ‘cos they’re loaded) b) patriarchal bullshit c) therapists always* being shit in films *Okay, so therapists in films are not all shit (#NotAllTherapists) but they need to be recognised in the script as being shit if they are. Take, for example, Robin Williams in Good Will Hunting. He’s not set up to automatically be the one we should trust because he’s working through his own issues. This works. What doesn’t work is when you get a weird, creepy therapist like Keanu Reeve’s character in To The Bone, who is treated like some kind of cult leader. His behaviour is then validated at the end when she returns to the house, and we’re supposed to believe that it’s a positive outcome for her. It’s great that she chooses to take steps towards her recovery, but to go back to a place run by such a weird creepy bloke is simply bonkers. Keanu/doctor/therapist/perv/cult leader is seen as radical because he says the word ‘fuck’ a few times. ‘Tell those negative thoughts to fuck off’ he says. So insightful and professional. Then he basically tells her to grow up and get over it, she goes away and has her little epiphany and then realises he’s right. The guy who thinks he can cure eating disorders by taking them to dance in some fake rain, is ‘right’ all along. She should’ve reported him, or at least gone to another clinic. But then, the boy was there. Prince Charming. The pompous British twat who came on to her but then instantly body shamed her when she said no. The one who tried to force-feed her chocolate. The one who sat on a tree branch in her epiphany dream – the bit where she was dressed up like some kind of born again Christian angel virgin and he made everything all better by telling her she was pretty. Couldn’t the stepsister have been sitting on that branch with her, Ellen wearing her usual clothes? Can she not take steps to recovery without there being a man there to help, and without having to wear less eyeliner? Then there was the mother and the moon. That strange, inappropriate feeding bit where her mother cradled her like a baby. I can see the theory behind that and it was nice to have a slight resolution to their seemingly turbulent relationship, but…really? And the moon…God knows. For a character who didn’t seem remotely spiritual, this ending was a little bit of a stretch for me. But the point is, she reaches the stage where she decides to follow the path to recovery. The intentions are good overall, and above all it’s a dialogue opener. The strength of the film was certainly in it’s strong female characters and family dynamic, showing how eating disorders effect the whole family. I hope this movie helps people learn a little more about an under-represented topic in film and will open conversations about eating disorders and how we can help people and families affected. If you or someone you know is affected by an eating disorder, here are some recommended websites: https://firststepsed.co.uk/firststepsed.co.uk/ https://www.b-eat.co.uk/ A note about triggering FEELING TRIGGERED IS NOT A WEAKNESS. If you’re the sort of person who mocks people for being triggered by things they watch or read, or uses the term ‘snowflakes’, you need to take a serious look at what kind of person you are. You wouldn’t laugh if that person was a relapsed drug addict, or if somebody had an injury which flared up. It proves how we don’t take mental health seriously enough as a society. Many people have had difficult experiences in their lives which can be easily triggered, bringing up difficult emotions. If you’re lucky enough not to have this problem then please recognise that not everyone is the same. It is not cool to laugh at somebody who is upset about something. It shows a lack of empathy, and that frankly you’re just a d*ck. Be excellent to each other! Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. Warning: contains triggering subjects There have been a few serious attacks in the news recently. It’s hard doing the ‘normal’ adult thing at the moment, just getting up and going to work like it never happened. It’s a strange world we’ve built for ourselves. My thoughts are with the victims and their families and friends, and I’m eternally grateful to our NHS. I appreciate people not wanting to give the attackers airtime, but we need to notice something happening here – most terrorists are men. Need a statistic? Here you go: “Overwhelmingly, the majority of people arrested for terrorism related offences are male: of the 3,157 people arrested between 11 September 2001 and 31 December 2015, 92% were male.” - From ‘Terrorism in Great Britain: the statistics - Parliament UK’ I think we need to talk about this, but it’s a hard one to tackle without instantly having to do the who #notallmen thing. #notallmen #notallmen #notallmen Happy now? MOST terrorists are men. MOST MOST MOST. This is what we see. This is what we know. I am not placing blame, it’s merely an observation and I’m just asking how we can help because somehow we’re failing men. Recently, one of my favourite comedians got a whole lot of bother on social media for this: Again – MOST, not all. If you know you’re not one of the men we’re talking about, there’s no need to cause a fuss. After the attack in Manchester at the Ariana Grande concert, some people said it was purposely targeted at young women. From what I can gather, extremists don’t seem to like empowered young women taking control of their own bodies, so I could understand the logic. Extremists generally seem to want to incite fear and hatred, and want to feel powerful and in control to the point of killing innocent people and often even themselves too. Then there was the Portland stabbing but that was a white guy so he isn’t called a terrorist of course. He is a white supremacist who doesn’t seem to show any remorse for killing two men (and injuring one) who were standing up for two women on a train. ‘Famous’ Men’s Rights Activist Paul Elam was quick to start the victim blaming after the incident: If you’re unfamiliar with Men’s Right’s Activists (MRA’s), they’re mostly men (#notallmen) and they’re mostly not doing much for men’s rights (#notallMRAs) but instead are mostly trying to take down feminists (how many more times can I use the word ‘mostly’?) The thing is, I agree with some of the things they’re supposedly concerned about – father’s rights, domestic violence against men, high male suicide rates, to name a few. It’s just unfortunate that so many of them seem to be horribly racist, sexist and homophobic. They seem to dislike anyone who isn’t a straight white man. This is only based on my short ventures into the ‘manosphere’ (a general name for the men’s rights online community), so I realise it’s from my limited perspective. If you are an MRA and you have a campaign you’d like us to join to legitimately help men’s rights, then do come forward. Many women might be happy to help you out. I have to protect myself from going too far down the terrifying rabbit hole known as the manosphere. There’s so much hatred there. But I’ve been trying to understand masculinity and how men are becoming so angry they’ll stab people on trains, blow themselves up or drive vans into crowds. Not forgetting, killing themselves too. The male suicide rate in the UK is three times the female rate.  Maybe gender expectations are one of the roots of the problem. I might be seen as too compassionate but I’d rather try to understand why these men have such a lot of anger. In my experience of Men’s Rights Activists online, they seem bitter and hurt and are looking to provoke people, especially feminists, into saying something horrible to them. When people retaliate, it then proves their point. It proves their ‘free speech’ argument right, validating their view that they’re the real victims, hence making them even more pissed off about it all. However, maybe they are the victims. Maybe they’re victims of a society that tells men not to show emotion. We tell boys not to cry. We tell them to be strong and tough. We teach them that anger is the only acceptable emotion. They have to play with boy toys which are often more violent than girls toys (but girls have equally damaging gender role expectations in a different way). They’re taught to ‘man up’ to deal with their problems. They’re taught that asking for help is a weakness, and that kindness and compassion are girly and weak traits. Men need gender equality just as much as women, sometimes I think even more so. ‘Feminism’ is a tricky word now because MRA’s see feminists as being cruel and angry, which some of them are. They’re pissed off from a lifetime of living by the rules of the patriarchy so I can see why, but it’s no excuse to be hateful. However, there are a lot of feminists, like me, who think feminism means the same as gender equality. It’s just a word anyway, what matters is the intention behind it.  These men, so unhappy with the imbalance of the world, are affected by the same patriarchal society that feminists are so unhappy about too. If there was just a way for there to be a compassionate, understanding dialogue between the two groups, we might find a way forward. But both sides are firmly in their opposing online worlds, having their own little bickering sessions amongst themselves. Feminists are arguing over who can be the best feminist (and over what the word actually means for that matter) and MRA’s are too busy having competitions about how masculine they can be (they have a whole Alpha/Beta thing going on). And through just literally typing that last sentence, I realise how ironic that is. It seems like gender equality is treated as a luxury, but it’s really becoming a necessity now. People are dying, and that’s not solely the fault of toxic masculinity of course, but surely there’s no harm in giving it a go. Gender roles aren’t helping anyone now and it’s time we moved on. We need to break the rules around conforming to be a ‘man’ or a ‘woman’. Just whatever you like. You don’t have to name it and you don’t have to justify yourself to anyone. We need an injection of empathy and compassion now. We need to try to stop placing blame and focus on what we can do, as individuals, to be kinder. Blaming Muslims or immigrants isn’t getting us anywhere. Terrorist attacks happen in the name of religion only in the minds of the attackers, but the basis of most religions is to be kind, forgiving and generally just don’t kill each other. It’s the person that kills people, not the religion. Often terrorists are quite young men who have been susceptible to radicalisation. We need to think about why they’re drawn into that in the first place and why they decided to become violent, unlike all the millions of other Muslims who don’t. Thinking about it, they might not be too different from the Men’s Rights Activists or white supremacists who attack innocent people on trains, or storm into schools with guns. Despite being the opposite type of extremists, both are angry at the world. Angry at people for treating them badly maybe? Angry for not having the power and control they think they deserve. I doubt whether these men had been shown another way to channel that anger.

The man who stabbed people on a train in Portland was said to have mental health problems. I’ve personally never seen this same consideration for Muslim terrorists. We need more provision for mental health services, but we also need to help break down the stigma around asking for help. If there is more acceptance around men showing emotion, there could be a chance of helping men who may want to hurt themselves or others. Kindness and be learned in the same way hatred can be. Our brains can always adapt, it just takes that initial push to start trying to see another perspective. We’re not going to solve the problems in society quickly, or indeed at all, but we can try to make a kinder, non-judgmental, equal world for the generations to come. Stay safe. Be kind.  Photo - Netflix - https://www.netflix.com/title/80179249 Photo - Netflix - https://www.netflix.com/title/80179249 Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different. Please be mindful of this, and that the content might be triggering, if you choose to read on. Trigger warning: rape, sexual assault and suicide. Contains season one spoilers. I just finished watching 13 Reasons Why on Netflix. Oh. My. God. We need to talk about this show. This is a really important series. It made me emotional. It made me cry. It made me feel down, but it was worth it. I was careful not to read anything about 13RW until I finished, so it was only then I discovered the backlash. I’d like to go through the negative comments and explain my take on them. Who am I? No expert, but I have a little insight. I work for a mental health organisation, am a screenwriter (a wannabe at least) and I was bullied at school (though it was before the days of social media so I guess I had it easy in comparison). Here are some of the negative responses I’ve come across so far: ‘Hannah is selfish and is overreacting’ If this is truly the way you think, please read up a little bit about depression and mental health issues. This is a very uncompassionate, selfish view to take, anchored in your own limited perspective. Where is your empathy? This view belittles her feelings and defeats the main points of the show. Hannah became so isolated that she felt nobody could help her and her life was empty. This was the result of the behaviour of people at school, but also because of bigger issues in our society of rape culture, gender inequality and sexism. 13RW is a statement on how mental health in teenagers, teenage girls in this case, isn’t taken seriously. If you think Hannah was selfish you might be the sort of person that thinks girls lie about rape or suicidal thoughts ‘for attention’, in which case you are part of the problem. Even if someone takes their own life ‘for attention’, they still made that choice so it’s almost irrelevant. It’s a cry for help, often too late. To think that girls are overly sensitive and emotional proves our social issue around kindness and empathy being weak traits. 'Helplines have got busier' “The Australian youth mental health service for 12–25 year-olds, Headspace, issued a warning in late April 2017 over the graphic content featured in the series due to the increased number of calls to the service following the show's release in the country.” - Wikipedia GOOD! If someone watches 13RW and makes a call to tell someone they were thinking about killing themselves, that’s one life that could be saved. If this show is making people speak out, how can that be a bad thing? ‘It never used the words mental health or depression’ Writers are told to ‘show and don’t tell’. 13RW relies on the audience to be able to recognise that Hannah’s mental health problems without the writers having to spell it out. Sometimes certain words can put people off if it seems like buzzwords or jargon. For instance, saying rape culture, feminism, heteronormative, might alienate some audience members. Feminism has a bad reputation (I don’t agree with that, I’m just sharing what I see all the time online). To make a TV show which demonstrates feminist issues instead of using words which might put people off is a powerful and influential way of telling a story. After all, if you’re going to raise awareness and change minds, you need to write in a way your audience can understand. ‘It glamorises suicide’ Oh, like Trainspotting glamorised heroin? I was teenager when that came out and the last thing it made me want to do was take heroin. In fact, it put me off taking drugs altogether. That had more of an impact than any anti-drugs talks at school. Often female suicide scenes in films are a little too beautiful, but Hannah’s death is realistic and painful, harsh and brutally permanent. Some schools in the US have sent emails to parents warning them about the show. Do adults know nothing about young people? I’m not even that young any more but it’s pretty obvious if you make a big deal out of something and tell kids not to watch something, they will find a way. That’s what I did with Trainspotting. Just accept that they’re going to watch it, and talk about it. ‘Hannah could’ve done more. Clay was there for her all along’ Hannah’s mental health problems got so severe that she didn’t have any energy to ask for any more help. People around her couldn’t recognize that there was a problem, much like many viewers of the show it seems. It’s sad that a lot of the events leading up to her death aren’t seen as anything unusual. This is how normal sexist behaviour has become. Hannah had a picture taken and shared without her consent, then put on the ‘hot list’, and then she was assaulted in public (when Bryce grabs her bum). I’m sure any girls would be familiar with these types of things, but it’s not normal. It’s not acceptable behaviour, and it should be passed off just because it happens a lot. That’s all the more reason to stop tolerating this kind of behaviour now. In terms of Clay, Hannah was not going to be saved by a love story. We have a major problem in our society with the ‘happy ending.’ The problem with most happy endings is that the heteronormative monogamous relationship, between two young people who stay married forever, is the epitome of perfect. We know it doesn’t always work exactly like that in real life, but we still hold it as the ideal. I bet a lot of viewers were hoping Hannah was just hiding somewhere, then Clay could save her and they’d run off into the sunset together. Happy endings give us unrealistic expectation of love, relationships, gender roles and happiness. Love does not equal happiness. How can a TV show which demonstrates the need to tackle rape culture and suicide be criticised more than the heteronormative, patriarchal rom-coms with thin, pretty women pandering to men? These films only add to the pressure on young people. Sometimes we have to watch something a little more challenging than a rom-com, otherwise we’ll never learn anything. ‘It says the other characters should blame themselves for Hannah’s death’ Many of the characters blame themselves but that’s part of their grieving process. I think the show is saying that schools can do better. That we – society - can do better. As Clay says, we all need to be kinder, not necessarily in a make-everyone-a-cup-of-tea sort of way (though wouldn’t that be nice) but rather try to understand why other people feel the way they do. Step into their shoes. This is compassion. There’s no harm in giving it a try. ‘There are too many high school tropes’ That's the point. Jocks, cheerleaders, nerds – as a screenwriter I’d be quick to point out stereotypical, overused characters in a high school drama. However, it was on purpose in 13RW to demonstrate how normalised their behaviour is. It holds a mirror up to society and shows us what we’ve become. The jocks rule the roost in American schools it seems, and we’ve got our equivalent in the UK. Everyone knows you need to at least try to be on the good side of the bullies or popular kids in order to survive school, which is why it’s hard to stand up to guys like Bryce. He’s the epitome of what our society sees as perfect masculinity – rich, white and powerful. Men like him grow up to be men like Donald Trump, and it’s clear there’s a lot of people who like him and his ‘locker room talk’. This has to change. ‘It's not realistic’ Despite the backlash, there are a lot of reviewers and people on social media saying how much the show had moved them and how they can relate to Hannah, I certainly can and it’s been quite a long time since I was at school! When Hannah said ‘but you’ve never been a girl’, it really stuck with me. 13RW is a harsh but true depiction of what can happen to young women growing up in a culture of objectification, toxic masculinity and rape culture. There are unfortunately too many Bryce’s in the world – rich white men, often athletes - protected because they’re at the top of the power food chain. ‘It's oversimplified – “be kind” doesn’t save lives’ True, but when Clay says ‘ we need to be kinder to each other’ I didn’t take that to mean ‘kindness can cure depression and stop people from killing themselves’ but that doesn’t mean it’s not true. People choose to take their own lives because of mental health issues, but there are factors in our society which are not helping. Rape culture ie normalised objectification, sexism, power over women, slut shaming, masculinity standards. We dismiss misogynistic behaviour as ‘boys will be boys’/’bro code’/’locker room talk’. We teach boys that being kind and compassion is weak, that they must hide their emotions and ‘man up.’ If you look at most of the terrorists and mass shooters in the world, not a lot of them are women. With the message that emotion and empathy equal weakness, it’s not hard to see why. Hannah is a demonstration of what could happen to girls growing up in a society of gender expectations and judgementalism. It’s a hard-hitting show because it has to be. People have been talking and writing about rape culture, consent and gender inequality for a long time but people weren’t listening. It’s taken a brutally harsh TV show to make the world sit up and take notice.  #bluenailsforhannah #bluenailsforhannah 13RW was hard to watch because it’s talking about the very things we want to pretend don’t exist. It forces us to notice. This is the power of storytelling. It has started a dialogue and might help chip away at the shame and stigma we’ve built up around such subjects. We need to listen to young people, many of them are loving the show. Instead of focussing on the suicide, focus on the reasons why – this is the point of the show after all. It makes no sense that everyone’s talking about the suicide, yet not about the gender inequalities which led to it. Instead of protecting people from seeing rape and suicide because it makes them feel uncomfortable, think about what we can do to address the issues which make girls like Hannah want to end their own lives. 13RW is a demonstration of the issues girls face simply for being female, and the expectation of boys to be more powerful, strong, and less emotional. For us to help, we need to not focus on protecting people from seeing suicide in a TV show, but rather break down gender rules and create a kinder, more balanced environment for everybody based on empathy and compassion. If you or someone you know is feeling low, take steps to find help. I work for a mental health organisation and many people tell me ‘I can’t call Samaritans, that’s just for when you want to kill yourself’ but that’s not true. Don’t wait until it gets to crisis point. Everyone needs to ask for help in their lives. We need to be kind and have compassion for others, but for ourselves too. Samaritans: phone 116 123 Recommended further reading - a brilliant article about gender equality by Natalie Bennett, one of the founders of TIGER Bristol. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|