|

In 2020, I finished my Foundation Certificate in Counselling and Psychotherapy, then applied to go to university to continue my studies… but I’d been refused full student loans and was freaking out. I was mad about the industry (I still often am) and I wrote about my experiences here. I honestly thought I might ruin my career before I even started, I was so scared to share my thoughts. Now, two years on, thankfully I am on the degree I applied for after a nerve-racking “Compelling Personal Reasons” appeal to Student Finance. I used to hold counsellors up on a pedestal. The middle-aged, middle-class women I saw in my workplace were so different to me, I didn’t see how I could fit in. My Introductory course and Foundation Certificate was held in Bath where people laughed at the way I said “hug” (I’m from the Midlands but don’t have a particularly strong accent). It was as if some had never met a working-class person before. I struggled to speak up in group work, which I now think was partly about class and power but I didn’t have the words to explain that back then. Our short “diversity” session (a tick box exercise in my view) resulted in most people not saying a word for fear of getting something wrong. I realised I spent most of that year sitting in groups with very polite middle-class people wanting to be seen as the Nice Middle-Class Counsellor Who Treats Everyone Equally ™. The problem with “treating everyone equally” is that it ignores, minimises and denies people’s experiences (the opposite of what we should really be doing as counsellors!) If I’d tried to talk about class on my course, it would likely have been met by a very awkward quiet room again. No doubt there was also fatphobia in the mix too, something I passionately write and train people on, fat working-class people often getting the brunt of the blame for being a “burden on the NHS”. This is no disrespect to my course pals, they were lovely so I don’t want to point the finger at people but rather look at this on a systemic level. There are a lot of Nice Middle-Class Counsellors ™ doing great work in this industry, and the issue is not individual counsellors but the lack of intersectional approaches, diversity and inclusion from the top. When coming to the end of my Foundation Certificate I was asked why I wasn’t continuing at the same college (seen as one of the “gold standard” colleges) to which I told them I couldn’t afford it as they offered no financial help. The response I got was either “but you can pay by installments” (erm, where do they think that money is magically coming from?) and “we have a bursary”, which is for a person of colour. I am not a person of colour. That bursary should go to a person of colour, but did it? Being in Bath their answer is often, “it’s a white area” but a number of us were travelling from Bristol so that just seemed like another excuse. I got the sense that their “one bursary place” was more about them trying to be seen as a Good College For Nice Middle-Class Counsellors Who Treat Everyone Equally ™. There are lots of these colleges, so I am by no means singling this particular place out. These training establishments offer very good training, there’s no doubt, but only for a specific demographic. I have various privileges which meant I could train at the college in Bath, if only initially, but also I have managed to pay for all the *extras* of which there are a lot in counselling training! Insurance, membership body fees, supervision, personal therapy, transport costs… There’s a lot to take into account so even with student loans (which don’t cover much in terms of living costs) it’s A LOT, and that’s without factoring in having to work for free (for me in two different placements) to build up placement hours. This isn’t to put anyone off who wants to train to be a counsellor but this is the reality and is a large part of why the industry is so white and middle-class. Going to university in Newport (Wales) to do a degree in counselling was very, VERY different from the college in Bath – OBVIOUSLY. But for me, I was relieved to find myself in a place with a slightly more varied cohort, I say “slightly” because of course it’s still mostly women. I’ve always found it strange that an industry built on theories by mostly men is so dominated by women. Through speaking to various trainee counsellors at different training establishments, I’ve personally started to notice a theme; there can be a tendency for the universities/colleges to prepare trainees for lower-end wages in charities or agencies, whereas the private colleges (where you need to pay for it yourself as they don’t offer financial help/loans) set people up to go into private practice. One particular college I heard about doesn’t require students to do placements in agencies, but instead students go straight into PAID private practice. These students are the ones who can afford this privilege of course, so predominately white middle-class middle-aged people, who are being trained to immediately see mostly middle-class clients. These colleges, and students, may not talk about class, race or any other “difference” because they are being primed to stay in a middle-class bubble. These private colleges almost feel cult-like to me sometimes; they like you to see therapists and supervisors who have trained with them, then train to be supervisors with them, all “keeping it in the family” (cult), conveniently continuing to make more money out of students. These colleges don’t want working-class people, or people from marginalised groups, as they need to uphold this elitism. This is the same in many other industries of course; money comes first and they always make sure they maintain their power at the top. Of course the membership bodies mirror this too. It also means these colleges don’t have to change their curriculum to accommodate anyone “different” (I put this in quotation marks because what is “different” in this sense is only ever decided by those power). They can do their few hours of “difference and diversity” to tick a box, whilst sticking to the same old theories mostly written by middle-aged middle-class men. There are very few undergraduate degrees in counselling, like mine, in the UK. Most courses are at Master’s level, which is another major form of exclusion as you can’t do these courses unless you have a degree. My course is Integrative with a splash of Pluralism – a concept popularised by influential white middle-class men who tell us we should “prize diversity” (Cooper and Dryden, 2016). I’m glad be on a course with a little more “diversity” and to be learning more modern approaches to integrative therapy. My course had a online counselling module long before the pandemic – ahead of the game! Online counselling allows for more inclusion, for both counsellors and clients, so it’s important in my view to not rush back to “normal”. I think “normal” was old-fashioned, exclusionary and snobby, and I’m delighted to be part of a changing counselling industry that can offer more flexibility, adaptability and inclusion. Attendance and able-bodiedness has always been a focus in therapy (for both clients and counsellors), some courses insisting on 100% face-to-face attendance. Chronic illnesses, disabilities, social anxiety, work and family commitments, and many other factors can make it difficult for people to attend in-person, both counsellors and clients. Our training providers and membership bodies need to reflect that by valuing online learning (and counselling) and supporting students by meeting their needs. If there’s a silver lining of this awful pandemic, it’s an opportunity to work towards the kind of accessibility we should’ve already had in the industry.

This year has taught me the importance of needing to be adaptable, creative and open-minded in the ways I offer counselling, and how this can still be done in a boundaried and ethical way. I continue to learn and remind myself of the natural neurodiversity amongst people and how everyone needs to communicate, learn and engage in different ways. I continue to keep learning and checking my biases about race, gender, sexuality, body size and appearance, neurodivergence, disability, and more, because this is so crucial for working ethically, and I always encourage other counsellors to do the same. I’m continually grateful for the privilege of being able to do this work with clients in my placements, in my job as a group facilitator, and running training and workshops. I’m sure my last year is about to fly by and I’ll be writing another follow-up blog before I know it as a qualified counsellor! I'm running an online body acceptance workshop on 13th July - find out more here!

0 Comments

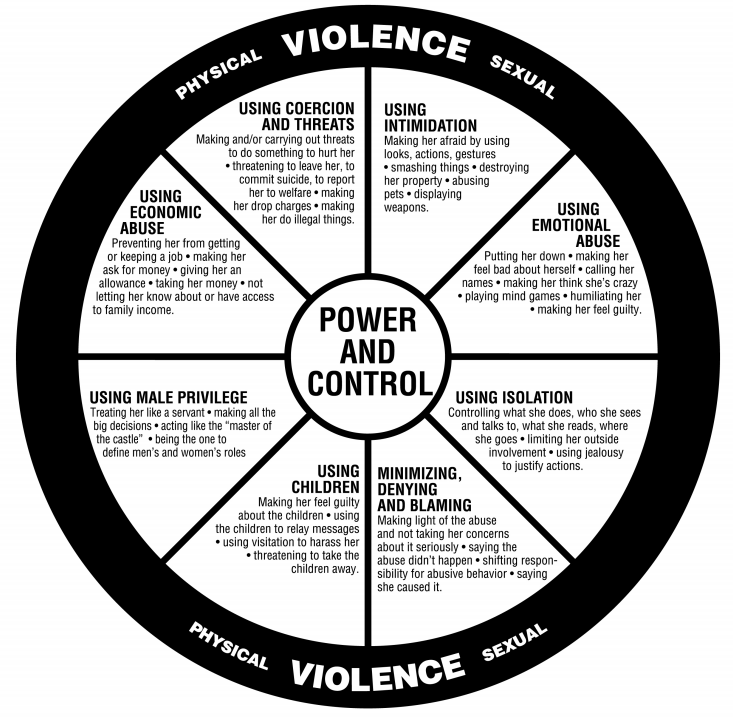

Content warning: domestic violence and abuse I work in domestic violence services and I’ve been horrified to see the public display of toxicity around the Johnny Depp and Amber Heard case. It’s EVERYWHERE. Memes, jokes, videos, GIFs, hashtags… mostly mocking Amber Heard, labelling her a “liar” and a “psychopath”. It scares me how much of an impact this has had, with such hatred on social media, showing the way our society sees domestic violence and abuse (DVA) and who we label “victims” and “perpetrators”. I’m not going to outline details of the case as there’s tons of information out there, I’m more interested in the impact on a social and cultural level. I work with perpetrators and am a trainee counsellor, so I have an interest in understanding how and why abuse happens. I take a big-picture approach when thinking about wider systems of power in which abusive relationships exist. I care more about the impact of this case on “normal” people, rather than debating the toxic details of two super-rich privileged celebrities. “Real” abuse It seems many people still view “real” domestic abuse as physical violence. There are many other forms of DVA, including emotional, financial, sexual etc, and lots of forms of coercion, manipulation and control. The breadth of DVA is shown in the power and control wheel later in this post (just one example, geared towards male perpetrator work). Physical violence is just one aspect of DVA, but all kinds of abuse are damaging and are traumatic. Perpetrators can use this idea of physical violence being the “worst” to position themselves as different to the “bad guys”. They reassure themselves by minimising and denying their behaviours, thinking they’re “not that bad”. They can say to themselves “but I’ve never laid a finger on her” or “I’d never hit a woman” to try to show they’re a ”good guy” and normalise their other abusive tendencies. This is to protect themselves from shame, a very difficult emotion to process, whilst allowing themselves to continue to feel the power and control of using their abusive behaviours. The memes of “real victims” side by side with Amber particularly upset and angered me, the “real victims” having bruises and black eyes and Amber looking fully made-up and beautiful. This idea of needing to have bruises or it doesn’t count only maintains our society’s limited views of DVA, stops victims speaking out, and colludes with perpetrators. The #metoo movement showed us how little women are believed, and often blamed. Examples include “what was she wearing?” and “was she drunk?” in relation to sexual abuse, and “why didn’t she just leave?” in relation to DVA. There have been many cases of men who have been convicted for abuse recently who are cast out by the general public immediately as monsters. But Johnny Depp (who has used abusive behaviour) is held up on a pedestal as one of the most beautiful men in the world. He’s rich, successful, loved and treasured as beloved characters in many people’s favourite films. The world was very quick to take his side as the victim, and Amber as the baddie, losing all nuance and treating it like a movie. This media circus completely dehumanised both of them, making it more about entertainment than a toxic relationship between two traumatised people. This case was not about who perpetrated the abuse, it was about Amber talking about her experiences. But it has been received by the public like a black and white, good vs bad, victim vs perpetrator case, and so now the perceived baddie must be punished. It almost feels barbaric and medieval, except now we use Twitter instead of throwing tomatoes at people in stocks. The social context Domestic abuse is always operating within wider systems of power and inequalities. It’s not just about the two individuals involved, it’s about the culture and society they’ve learnt from growing up, including gender expectations. We also live in a culture that elevates celebrities to a powerful untouchable level, especially when they’re very attractive. In a relationship, no two people are ever completely equal. The social context in heterosexual relationships can often mean that the man holds more privilege and power (although it may not feel like it to him). Privilege in this sense isn’t about your job or how much money you have, it means that there has traditionally and historically been more power afforded to men. I know many people think we’ve moved on from that now but we can’t just switch off hundreds of years of historical oppression. It’s still with us, under the surface. Johnny Depp is, was and always will be more powerful than Amber Heard. He is a rich, powerful man who holds an extremely large amount of privilege, entitlement and power. And now he’s becoming a poster boy for male victims in a society very quick to continually remind us that women lie and women are abusers too. Unfortunately, he’s more likely to be a poster boy for male perpetrators who want to paint themselves as victims, so I fear this won’t help male victims much at all. “But what about women?” Yes, women can use abusive behaviour - anyone can. But there are systems in our society that influence who becomes abusive and how, and cis-gender men are often the ones presenting as perpetrators, in terms of domestic abuse towards women but also violence towards other men and other violent crimes. I’m not saying this because I’m a man-hating feminist, I’m saying this because male violence is everywhere around us, all the time. How many more school shootings do we need before we talk about this? My work with perpetrators has always been with heterosexual men, and I’m often asked (and to be fair I asked this question too initially) “why are there no perpetrator interventions for women?” Overall, there is very little funding for perpetrator work (there’s barely enough for victim services) but if there was maybe there would be scope for different sorts of programs and interventions. So with the little funding there is, the largest group of perpetrators is the starting point, and that is men. I don’t think we’re very good as a society at holding men accountable without someone doing the “what-about-ery” and shouting “not all men”. Obviously, it’s not all men. But saying this just distracts from the problem. There are systems of power and entitlement in our society that mean that abusers, rapists, paedophiles, mass shooters and terrorists are often male. We just don’t talk about it. The more we distract from this, the more we’re moving away from being able to help and support victims. I personally believe we need to hold these men accountable without blaming and shaming them, to be able to help both them and victims. Being a “victim” also doesn’t mean being perfect and innocent, this is just a stereotypical idealistic view. Many victims fight back to protect themselves. Many are pushed to extremes and use violent behaviour. We need to understand the reasons for this and take an understanding and nuanced view of these dynamics. Masculinity standards and gender expectations Male perpetrator work is often psycho-educational and keeps women and children in mind whilst assisting the male perpetrator to challenge and change their own behaviour. The work can be based on unpacking messages around masculinity and gender expectations, and narratives around what women’s roles “should” be and what healthy relationships look like. It can be about looking into past experiences or traumas, and connecting the dots to current behaviours, without excusing them. Groups for men can be very powerful as they’ve often never been in spaces where they can build trust with other men, talk about emotions safely and be heard. In my experience, many male perpetrators don’t see themselves as being emotional people. Learnt behaviours from earlier in life and masculinity standards have meant they’ve been told not to cry or show any of the “weaker” emotions (associated with women). Instead, these emotions can then get funnelled into anger. Many people I’ve worked with don’t realise that anger is an emotion. They think they’re not “emotional people” when in fact they’re very emotional as they’re getting angry all the time. It’s a societal and cultural narrative that pushed them into only showing the “acceptable” emotions for a man – anger. A lot of work done with perpetrators is to help build awareness and shift their perceptions, joining the dots to understand their behaviour and understanding ways to manage and change it. In a relationship there are two people’s sets of dots, made up of gender and sexuality expectations, childhood experiences, trauma, attachment styles (how they relate to people and how they act in relationships) and how they regulate their emotions. It’s a bit like a jigsaw of all these aspects, trying to fit together. Sometimes they do fit, often it takes a lot of work, sometimes it’s a scattered mess, which is what I think Amber and Johnny are. In an ideal world, they just need to take their own separate jigsaw pieces off in opposite directions, tidy up their own bits, and move on. In other words, focus on healing themselves individually, outside of their toxic relationship. It’s unlikely this will happen unfortunately. People in difficult relationships often take patterns into the next one. In Johnny and Amber’s case, there seems to be a co-dependency, especially as it now seems Amber will be appealing the verdict. This whole case is an extension of the toxic power dynamics and abuse, and it looks like it’s not going to stop any time soon. Both are determined to be a victim and cannot walk away from each other it seems.

The impact on the general public The real victims of this are the people watching. It’s people stuck in abusive relationships who see their friends post memes on social media mocking Amber. It’s the general public who are being shown an inaccurate portrayal of abuse, and it’s men who will now be able to ignore/justify/defend their behaviour more than ever. This case will scare victims off speaking out about domestic abuse, even if they don’t name their abuser. It may keep people in toxic relationships, doubting themselves, thinking that they’re not a “real victim”. But the impact on perpetrators really concerns me too. There’s no doubt there will be a rise in defamation cases. Perpetrators often see themselves as victims, so this case will validate this for many. Any perpetrators who were starting to question their own behaviour, may now stop. They may think “maybe it was her all along” or “I knew she was lying”. Perpetrators engaging in interventions may drop out now as they have another reason to minimise and deny their behaviour. The repercussions of this very public, messy celebrity case is catastrophic for everyday people, be it victims, perpetrators and arguably most importantly – any children involved. What are we teaching the next generation? Seeing this unfold has affirmed to me that things are never black and white. Our society’s narrative is that there must be one victim and one perpetrator, but it’s way more nuanced than that. The Depp Vs Heard case wasn’t even about that but the public wanted a good vs evil battle. Amber, whether you think she is a perpetrator or not, does not deserve to have death threats and be hated in the way she had been. Abusers are not born evil, it is learnt behaviour influenced by our own societal views. In that sense, we help create perpetrators, but we can also help them change. It's all about the nuance Johnny Depp and Amber Heard have both perpetrated abuse, and this has been called “mutual abuse” but this does not mean it is equal. When a man holds this much power, it will never be equal. When women are silenced and not believed, I’m reminded that we have not yet reached gender equality. My plea is that people look at the bigger picture and see the larger systems of inequality, power and privilege involved. I would like people to understand that domestic abuse is not just about bruises or having “proof” but about power and control in more subtle ways. As an example, if a man puts his wife down for years, making digs about the way she looks, discourages her from seeing her friends, controls finances, makes decisions about their relationship based on what she “should” do as the woman and how he “should” act as the man… what happens when she snaps and physically pushes him or hits him? Is she the abuser and he’s the victim? We need to look beyond the physical violence and understand coercion, control and power. It’s never as simple as whoever proves they have bruises wins. My personal interest in working with perpetrators has always come from wanting to be part of a deeper solution, instead of just helping victims leave abusive relationships. Obviously a person’s safety is always the most important thing initially, but when we help people get out of toxic relationships, they can be drawn into others. Helping tackle to root of the power and control issues in perpetrators is crucial long-term work, and in turn helps victims and children. My empathy and compassion extend to perpetrators as I believe there are complex lifelong issues that lead to perpetrating abuse (childhood development, attachment etc, but this post is too long already to go into that!) Perpetrators are people who have learnt certain behaviours to be able to cope. I believe we can help them and help victims. But we can’t help anyone caught in toxic relationships if we keep these short-sighted societal views of domestic abuse. We can use this Depp vs Heard case as a learning curve, holding a mirror up to our society to show us that our views of domestic abuse must change if we are going to support victims and help the next generations. Freephone 24-Hour National Domestic Abuse Helpline: 0808 2000 247 or visit www.nationaldahelpline.org.uk (access live chat Mon-Fri 3-10pm) |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|