|

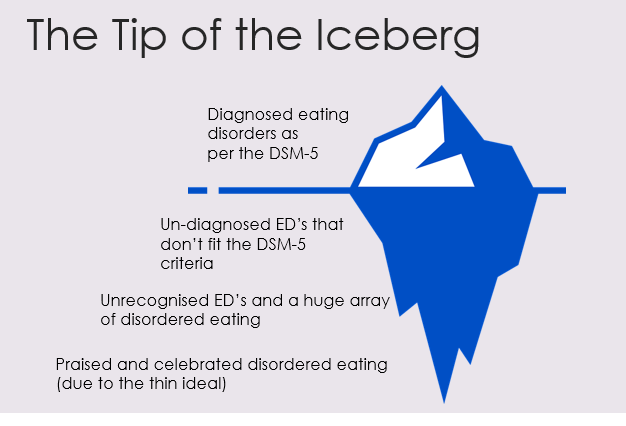

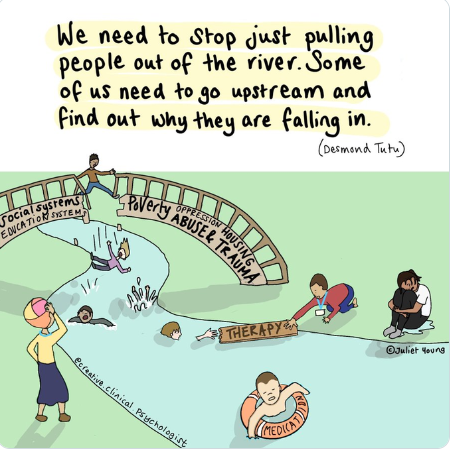

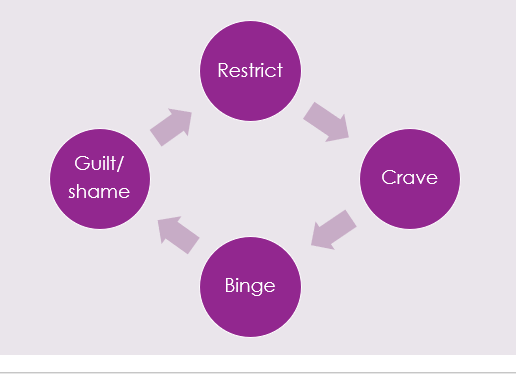

What do domestic abuse and disordered eating have in common? How do they intersect and interplay? In this blog post, both my working worlds come together in a discussion and reflection on similarities and intersections I see between disordered eating and domestic abuse, for both victim/survivors and perpetrators. A note on language: I use the term “victim/survivors” as different people prefer different terms. I may speak about perpetrators as male, though I’m aware other genders can be perpetrators too, but I predominantly work with men. I also am speaking in binary terms in this post, but would like to highlight how trans and non-binary people are particularly vulnerable to abuse and disordered eating.  Photo by Sydney Sims on Unsplash Disordered eating Let’s start with what disordered eating actually means… well, different people define it in different ways, but for me, I like to use it as an inclusive term for eating disorders and any distress around food or exercise, irrelevant of diagnosis. Sadly, many people find it difficult to get a diagnosis of an eating disorder, and many struggle to access any help due to cultural or societal barriers. I’ve heard the “not thin enough” rhetoric too many times now from people who have been turned away from NHS treatment. BMI (body mass index) is often still used to gatekeep services, even though the NICE guidelines say otherwise, but NHS services are overstretched as it is. Despite what many people think, most people with disordered eating are at higher weights (Duncan et al. 2017) A study by Hay et. al. (2017) showed that anorexia nervosa was only 8% of all eating disorder cases, which may come as a surprise to many. The most prevalent is "other specified feeding or eating disorder" (OSFED), because unsurprisingly, eating disorders do not fit the tick boxes easily, and most people are not thin. The stereotype of the thin white teenage girl with anorexia is overused, however, access to treatment requires a level of privilege, so treatment and research is often based on this limited demographic. I created this image, which I use in my workshops, to show how I view disordered eating and how diagnosed eating disorders are just the tip of the iceberg. Eating disorder treatment can largely be focussed on anorexia nervosa because it does have the highest mortality rate, and people are often very unwell by the time they access NHS treatment. The idea of being “not thin enough” for treatment means that people are losing even more weight, exacerbating the eating disorder. The system is very much “firefighting” we might say, with people only getting the help they need when they are at crisis point. I liken this to domestic abuse services… there for when people are in crisis and are trying to flee an abusive relationship. For eating disorder recovery, the goal is often a “healthy” weight on the BMI chart, in domestic abuse it’s often to get out of the relationship. Neither of these solutions fully help the issues, it’s just dragging people out of the situation that they will enviably end up back in again because the deeper-rooted patterns and issues are not being addressed. My view of both takes a “zoomed out” approach, considering the bigger picture of societal and cultural issues we need to tackle to help prevention. Both disordered eating and domestic abuse sit within a context of patriarchal rules and gender expectations, systems of oppression around race, body ability and size, gender, sexuality etc. Poverty and food insecurity plays a huge role in relationships with food and is a contributing factor to disordered eating. Striving for weight loss is often at the root of why disordered eating develops in the first place (though not for everyone), because of our social and cultural reliance on thinking that thinner is better. There are many different influencing factors, which is why eating disorders are so complex and need to be viewed through an intersectional lens. Domestic abuse I work with perpetrators of abuse, which is my way of trying to go upstream. Helping people leave abusive relationships is so important of course, but we need to go to the root of the problem, which in many cases… is men (#notallmen etc etc). YES, I KNOW OTHER PEOPLE CAN BE PERPETRATORS, but my work is mainly with men because they are more likely to be perpetrators of abuse. I’ve written another blog about my work with perpetrators, which you can read here. I am not here to blame or point fingers at men but rather help the ones that want to be helped. Not all of them want to be helped of course, but many do want help to manage their anger and change their behaviours. This is how we break the cycle, so people don’t end up in other abusive relationships, and so that kids don’t grow up to normalise abuse. Victim/survivors and children are always at the heart of perpetrator work. What do both domestic abuse and disordered eating have in common? Control. Disordered eating and body image problems can be a form of coping, to try and regain control when other aspects of life feel out of control, or when things from the past have created a need to feel safe. Domestic abuse is about control, a fear of feeling out of control and sometimes a deep fear of abandonment. Many victim/survivors, and perpetrators, have experienced trauma or difficulties in childhood, which can contribute to needing to feel in control to feel safe. For male perpetrators, masculinity expectations in our society (e.g. strength and dominance) and the impact of living in a patriarchal society, and power and privilege, can all contribute to an abusive relationship. Domestic abuse takes many forms, coercive control being a more subtle, manipulative way of controlling and silencing victims. A person’s body and appearance can be a target for a perpetrator who may want to isolate their partner. They may make subtle comments about what they’re wearing or about their weight to fuel the victim’s body image concerns, which in turn can discourage them from going out. For a victim/survivor of domestic abuse, weight and appearance might be one thing that they feel they can control. They may need to be fixated on weight loss to meet a standard their partner expects, or it may be to avoid weight-shaming comments from them. They may experience this like gaslighting, it’s their own fault they’re fat (which they may feel means “unlovable”). They may be judged for what they eat by partners, or if money is tight they may be made to feel guilty about eating. They may prioritise feeding their kids, they may have to rely on food banks and feel ashamed. Kids can sometimes refuse food as it’s their only way to communicate that something is wrong when they don’t have the language that adults do. These are just some examples, there are many ways that food and appearance can intersect with domestic abuse, both as a coping mechanism for victim/survivors, and as a method of control used by perpetrators. Exercise and steroid abuse Although men obviously do struggle with eating disorders too, men may find themselves leaning to exercise and “bulking up”, which we could speculate as being a quest to feel more masculine perhaps or a way to feel stronger and in control when they feel emotional and vulnerable. “Muscle dysmorphia” can lead to over-exercising and the use of diet/protein products to build muscle, and there is a risk of steroid misuse. Anabolic steroids are legal for personal use, but it is illegal to supply or sell them, though this does not stop people from buying them online or through gym contacts. This is particularly dangerous as there could be anything in them. Anabolic steroids can increase anger, anxiety, aggression and hostility (Oberlander and Henderson 2012) as well as having physical effects and the risk of becoming psychologically dependent. There is a documentary by Reggie Yates on YouTube called “Fatal Fitness: dying for a six pack” which highlights many of the issues with exercise and steroids affecting men. The eating disorder voice Many people in recovery from an eating disorder speak of the “anorexic voice” or “eating disorder voice” - the critical thoughts that shame them and tell them what to eat/what not to eat. This voice, many say, is like an abusive partner (or parent) in their heads. That part can’t just be switched off, they can’t escape it, because it’s deep-rooted… it’s similar to how a victim can’t easily leave a perpetrator. The cycle of abuse is decidedly similar to a binge and restrict cycle: Shame plays a big part in this. With perpetrators we talk about the “pit of shame” and how hard it can be to get out. They can feel ashamed of their behaviour but sometimes unable to break the cycle, falling back again, feeling out of control when they get angry. For victims, trying to leave isn't just about building resilience and strength, it’s literally about safety, as the risks can skyrocket when they separate. The risk of stalking harassment and even homicide increases after separation. In the same way that victims stay in relationships to try and keep themselves safe, people hold on to disordered eating for that same safety. There is a great story/metaphor by Dr Anita Johnston about clinging to a log in a fast-flowing river. Even when you reach calmer water, and there are people on the river bank who can help you get out, the log saved your life so it’s hard to let go (the video is at the end of this blog if you’d like to watch it in full). This is meant to demonstrate the power of disordered eating, but can equally demonstrate the difficulty of leaving an abusive relationship. Both domestic abuse and disordered eating are about power and control ultimately. Both are linked to trauma, and cannot be separated from systemic issues and inequalities. However, it’s important to work in a case-by-case, client-centred way, honouring their unique experience and intersecting aspects of identity. If you’re struggling with any of the issues discussed in this blog, I offer counselling sessions online – find out more here. If you’re looking for more information and training on disordered eating, I’m offering a workshop through Online Events on 27th September. I also plan to run training elaborating on this blog, on domestic abuse and disordered eating, so if you want to be updated on this please sign up to my mailing list. Resources

BEAT Helpline: 0808 801 0677 https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/ First Steps ED: https://firststepsed.co.uk/services-and-support/ (counselling, befriending, groups, workshops and more) Anita Johnston log video:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|