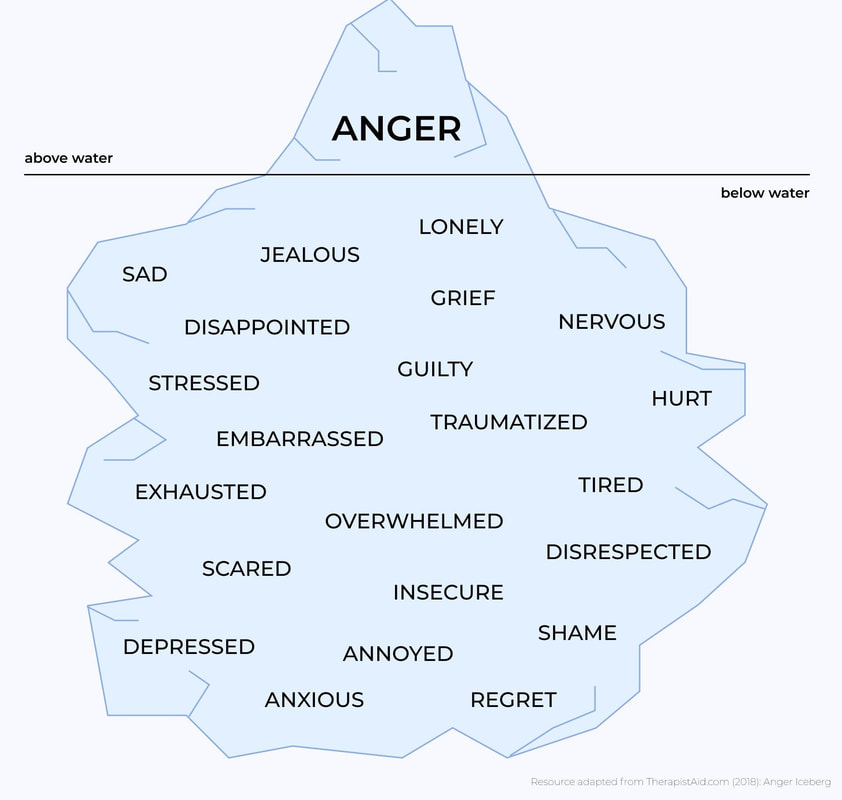

Everything you’ve always wanted to know about perpetrator programmes but were afraid to ask10/13/2022 I did a talk about my experiences at the Boys at the Crossroads conference on 12th October in Bristol, for more information, click here. I’m a group facilitator on a Domestic Violence Perpetrator Programme, which, if I ever got invited to fancy dinner parties, would probably go down like a lead balloon, as the saying goes. But really, people are usually intrigued, some are just less afraid than others to ask questions! This blog contains my honest reflections and experiences of being a group facilitator working with men who have used abusive behaviours. My workplace and the overarching research are mentioned, but these views are my own and are not of my employers, the researchers or the programme creators. Confidentiality is of the utmost importance here too, so I won’t be using any names or identifying factors for individuals, but will sometimes refer to “group members” generically as a collective when talking about patterns and themes. The language is binary due to the nature of the programme I work on as it’s for cis-gendered heterosexual men only, but I just want to flag up the vulnerability of trans and non-binary people being abused by partners and family members, also male survivors of abuse. None of these things are talked about enough. What is a perpetrator program? Programs and interventions vary in different areas, so my experience is only based on one; a 26-week intervention for men who have used abusive behaviours toward their partners or ex-partners. The weekly group sessions are 2.5hrs (with a short break) and involve a check-in at the start, followed by a led session based on themes and content from the programme manual. The sessions focus on different aspects of abuse, ranging from what abuse is (which is very important due to the misconception that only physical abuse is “real” abuse), sexual respect, anger management, attachment theory, CBT (cognitive behaviour therapy), emotional regulation, and more. It’s not something the men can do as a quick tick-box exercise to appease social services, it’s a long intervention and it’s challenging. It takes commitment, bravery, responsibility and accountability, and it involves dealing with a lot of difficult emotions. There are very few perpetrator programmes in the UK (though areas differ) as proving that they work and getting funding is difficult (hence the reason for the research study). There’s no doubt that prioritising helping victims/survivors is crucial when it comes to funding domestic violence services, but this can lead to a lack of help for perpetrators who want to change their behaviour, which in turn helps keep their partners (and children) safe. Perpetrator work is crucial for long-term change in helping victims/survivors and their children, to avoid them going into other relationships with the same patterns of behaviour. The safety of partners, ex-partners, children and future partners is at the heart of the programme. Why just men? A question I’m asked a lot (and I initially wondered this too) is “what about women?” Well, studies show that men are far more likely to be perpetrators than women. I know that statement will make some people feel uncomfortable and may prompt the response “but women can be abusive too”. This is true, but this response steers the focus away from the central issue. It’s similar to saying “all lives matter” - it de-centres the current problem, making it harder to focus on areas for change. Other perpetrator interventions in other areas may accommodate women, but the particular model this programme is based on (the Duluth model) involves content specifically to unpack masculinity and issues of power and control in a patriarchal society. It’s sometimes called a “pro-feminist” model for that reason, though I personally would argue that working on the basis that patriarchy and inequalities exist isn’t inherently “feminist” but is rather just highlighting an issue that affects us all. Naming the patriarchal imbalances doesn’t have to be an attack on men (as is often assumed about feminism) as it can help men too; after all, the patriarchy is damaging for everyone and places various harmful expectations on men. In a wider social context, it can be difficult to talk about male violence (especially on social media) without there being a lot of anger and defensiveness. We do still live in a society based on historical patriarchal values and that can make it difficult to have conversations about male violence as it can be met with de-railing and gaslighting tactics (albeit sometimes not conscious). Powerful people often fear losing their power and want to stay in control, so equality is risky for them. It’s the same with individuals who use abusive behaviour, it’s about power and control and the fear of not having it. We need to centre what’s important to be able to make a positive change in the world, and that means we need to put aside our discomfort with talking about male violence and abuse. This isn’t about pointing the finger or blaming men, but rather looking at how we can help. Patriarchal values can be harmful, with narratives about being a “real man” and expectations of being “the provider”. The messages about being strong and not showing emotion are prominent in the group, and we do work around “the man box” and masculinity expectations to unpack these. Many of the men on the programme have never been in spaces where they talk about emotions, and certainly never with other men. Many would say they’re not emotional people while forgetting that anger is an emotion too. We sometimes draw icebergs to demonstrate this, with anger at the top and all of the other emotions under the surface; anger being the emotion often seen as more “acceptable” for men to show. As a facilitator it’s been amazing to see how powerful group work with these men can be. They share experiences, model new behaviours, and both challenge and support each other. The group allows a safe and boundaried space to start to process these difficult emotions without the judgement or stigma they may otherwise face for having the label of “an abuser”. What got me into this work About ten years ago (at the time of writing) I got a job as a receptionist at a counselling organisation, and like many newbies was given tasks such as stuffing envelopes. We had a domestic abuse signposting pack, which contained flyers for a perpetrator programme, and it instantly struck me as such a crucially important thing. I would never have dreamed that ten years on I’d be working on one myself! I was just a self-conscious receptionist, I hated groups and I never thought I’d be able to become a group facilitator, or a counsellor too…but proving myself wrong has been pretty awesome I’ll admit! When I was learning more about feminism and inequalities, I became quite fascinated by men’s rights activists, incels, pick-up artists and “men going their own way” (MGTOW), in the dark depths of the internet known as the “manosphere”. It was part horrifying, part ridiculous, and mostly infuriating. I was channelling my anger and processing some of my stuff no doubt, but I was also curious about where these kinds of views and such blatant misogyny stemmed from. Since then, I’ve trained as a counsellor (at the time of writing in my final year) and have benefited hugely from being able to look at both systemic and individual factors and issues which lead to abuse, both in my own time, my work and through studies. Personal experiences in my own life have led me to have increased curiosity about perpetrators of abuse and sex offenders, and understanding these client groups has been helpful for my own healing too. I still had doubts about if I was being naïve, especially as most other counsellors (and trainee counsellors) I met did not want to work with these client groups. I wondered if I was kidding myself; wouldn’t I be terrified sitting in a room full of abusive men? Often I get the sense that certain client groups are seen as “too manipulative”, “untreatable” or “resistant” (interestingly, eating disorders are thrown into these categories too, which is my other line of work), but this has only sparked my interest and passion further. I wonder how much these labels were more about the practitioners and their views, judgements and societal stigma. Born evil? Words like “perpetrator” and “sex offender” hold a lot of stigma and seem to spark instant fear, leading to them being quickly deemed as “monsters”. There’s a sense that they will never change, or can’t change, or even that they were “born that way”. This is absolutely not the case, even serial killers and “psychopaths” were not “born evil”, despite what the media would portray. It’s instead a complex mix of genetic and environmental factors which can create disruptions in early brain development. People are not “born evil”, this is a myth perpetuated by society, potentially as a way to focus on the ”baddies” and ignore systemic societal issues and trauma which influence this behaviour. It takes curiosity and compassion to look beyond the labels and stigma, and holding strong boundaries, and being self-aware and reflective, so supervision (group and one-to-one) is very important in this work. Perpetrators and offenders have often been hurt and traumatised themselves. This is not an excuse for their behaviours but it’s important we look at the potential causes and influences. Experiences are different for every individual, but themes can include violence or controlling behaviour in their home when they were growing up, substance abuse, poverty, trauma, mental health issues, and systemic inequalities and discrimination such as racism. The first few years of life is a vulnerable time and we know from various literature that not having your needs met and not having enough love in the early stages of life is detrimental for brain development. (I suggest reading Sue Gerhardt’s book “Why Love Matters” if you’re interested to learn more). This in conjunction with attachment theory (Bowlby), means that a child may grow up with an insecure attachment based on not forming secure relationships with caregivers when they were babies, which becomes a template for their relationships and their whole lives. Part of the benefit of group work is to form and grow relational bonds through relationships with the facilitators and the other group members. My expectations when starting as a group facilitator

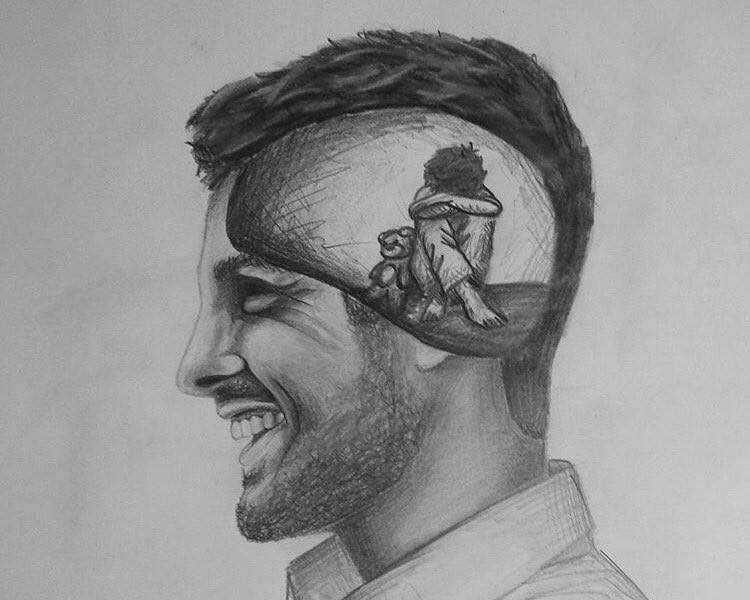

When you picture a perpetrator group, what do you see? Many new guys starting the programme have told us they expected Stella-swigging blokes in vests with tattoos on their necks. The men tell us they’re often surprised and relieved to find that it’s “normal guys” just like them. But sometimes, they may hope to find men “worse” than them, so they can position themselves as “not as bad as that guy”. This can happen with men who have not used physical abuse. They think they are not as bad as other guys because they’ve not been physical, but part of what we do on the programme is to go over all the other types of abuse and the impact – that emotional forms of abuse stick with women for years, if not their whole lives. There is no hierarchy of abuse in the group, they’re all there because their behaviour is impacting people negatively and they want to change that. I’ll be honest, I was absolutely terrified when I sat in on my first group. I knew that there would be men from all different backgrounds; a range of ages, working class and middle class, in different professions and from varying cultural background. But…how would I feel sitting with all these men that I knew had abused women? What if I freaked out? Cried? Got scared? I soon realised that many of these men were anxious and scared too, especially when starting the group. It can be terrifying for them, as they share the same fears around what to expect, but also there’s the worry of what we’re potentially going to put them through! Some of our role plays are hard-hitting, and we run empathy exercises (for instance asking them to sit in the role of their children and answer questions about the dad) which can bring up a lot for them, but it’s within a safe, contained and boundaried space. These men are dealing with a lot of shame, past trauma, attachment wounds, anxiety and many other factors, so safety and being “held” is vital. For me, being able to offer this “holding” and containment has been a real honour. I get to sit in a world that only a few see, and that feels like a real privilege and a gift. These men sit with really tough emotions and work really hard on their behaviour and self-development, and I find myself admiring and respecting them. This can create internal conflict in itself, forming relational bonds and feeling somewhat proud of the guys and the work they do, in the context of a society that says they’re “bad”. Many people have done bad things, but it doesn’t make them “bad” people. Underneath this behaviour there is often pain, shame and low self-esteem. The paradox for the men can be feeling as if they don’t deserve to improve their self-esteem, but this is needed in order to move out of the “pit of shame” as we call it (sometimes known fondly in our group as the “pit of sh*t”). My reflections one year on I started working for Splitz about a year ago (at the time of writing), which means I’ve done a full run of the programme (it’s continuous, so men join at different stages). The original members of the group who I started with have completed the programme, so there have been some heartfelt endings and it’s been lovely to hear the reflections from the men in their final group. I’m not involved in the research side of it, but if you ask me if perpetrator programmes work, then ABSOLUTELY. I have seen, felt and experienced it. Not everyone will be ready to change, but many are, and this can have an impact on their whole family. It’s so important that we see beyond labels, judgements and stigma to see the human being behind the behaviour. I like to believe that nobody is “untreatable” or “too resistant” or not worthy of help. Working on a perpetrator program helps take a bigger picture approach to domestic violence and abuse, by moving beyond the reactionary system currently in place, which often just involves helping victims stay safe in a dangerous situation. This just means the perpetrator continues their behaviour, and even if the victim can leave, they both risk getting into other abusive relationships in the future, so this approach isn’t helping to break cycles in the long-term. Helping perpetrators reflect on and change their behaviour is a vital longer-term approach to help break cycles of abuse, ultimately helping the next generations to come. Click here for domestic violence and abuse support organisations

2 Comments

Talking Tales, our friendly storytelling night in Bristol run by Stokes Croft Writers, made its return on 23rd September 2022 at The Wild Goose Café in Easton. The Wild Goose is a drop-in centre offering meals, hope and support to anyone experiencing insecurities such as hunger or homelessness, and it’s part of the charity InHope. Thank you to those who donated on the night (if you’d like to donate you can find ways to contribute on their website). This was the first face-to-face Talking Tales event since before the pandemic, so it was exciting to see familiar faces from the storytelling scene, plus new faces, and also participants from some writing workshops I’d facilitated upstairs at The Wild Goose, in conjunction with Arkbound, a charity book publisher founded in Bristol. Creative writing workshops I was delighted when I stumbled across an advert for a creative writing group facilitator, it fit my experiences and passions perfectly; creative writing and leading groups. In my other work, I run body image and disordered eating workshops and I'm a co-facilitator on a Domestic Violence Perpetrator Programme (blog coming soon about this!) As a writer myself, I’ve done lots of different writing workshops and courses, in the UK and in New Zealand (where I lived for a few years) and I’ve subsequently written in various formats – novels, novella, short stories, flash fiction, screenplays, blogs etc. Now as a student, I’ve been learning how to write academically too - quite a shift from creative writing! At the time of writing this, I’m going in to my final year of a degree in counselling and therapeutic practice. It was an honour to facilitate the writing workshops at The Wild Goose in conjunction with Arkbound (you can read more about the workshops in Arkbound's blog post here). It was important for me to be involved with workshop providers that prioritise and uplift voices not usually heard, which is exactly what Arkbound do, giving a platform to people from disadvantaged and diverse backgrounds. So many writing courses, workshops, groups and storytelling nights are filled with white, middle-class people - no offence if you’re in this demographic but this really limits the stories being told and the narratives spread. The influence that stories have (books, TV, films etc) is a crucial part of the systemic inequalities and discrimination people face in our society. Storytellers (and those who platform them) have power, and therefore a social responsibility. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie talks about the “danger of a single story” in her Ted Talk. Who gets to tell their story? Who’s voice is heard? Who’s narrative is deemed “normal”? I’ve personally felt uncomfortable being working class in many middle-class workshops and training (especially in the counselling world, which I wrote about here) so if it felt like that for me – a white person with various other privileges – it will likely be a hundred times harder for anyone of minoritized groups or disadvantaged backgrounds. For those familiar with my story “Zombies on a Boat”, this story was effectively a backlash against a snobby writing teacher who spoke down to me and criticised me for not writing "like Hemmingway". Creativity certainly isn’t cultivated and inspired by being told there is a “correct” way to write, so I find it more important to facilitate groups that cultivate safety and respect. People often write for their mental health and share personal things; it can be therapeutic, processing difficulties in life. Whether you write true stories or not, there’s always an element of you in them, and so this needs to be celebrated, not squashed with too much emphasis on the writing “rules”, perfect grammar or going at it too hard with the red pen. The workshops at The Wild Goose ran for 8 sessions, alternating between myself and another facilitator. We covered topics such as getting inspired, plotting, character building, motivation, imposter syndrome, building confidence, and publishing. The idea to run Talking Tales came about only a few sessions in, as having a storytelling night to finish off the workshops seemed like a perfect way to celebrate the participants, whilst reviving our beloved event. Talking Tales storytelling night Talking Tales #30 (yes, the 30th one!) was a roaring success with a packed full house, filling every chair in the café! I hosted the night, a sequin triple-threat in sequin trousers, a sequin top AND with a sequin notebook. The pink power jacket topped it off, giving me the fake-it-til-you-make-it confidence I needed! My homemade disco ball earrings only fell apart once, which is the real achievement of the evening. Our performers were astounding! We had a wonderful mix of short stories, even shorter stories and spoken word, from incredibly talented writers of Bristol and beyond. Our performers: First half Jonathan Evans Shakara Elaine Miles Claire Barnard Second half Fin Phil Mac Oliver Kennett Shakara (link in first half list) Tony Thatcher Mark Rutterford Please follow and support these writers! I’d like to thank Shaun Clarke from the Urban Word Collective for introducing us to Shakara and Phil, two awesome spoken word/poetry creatives. Check them out on Instagram (linked to their names above) and check out the Urban Word Collective anthologies - Lyrically Justified. If you'd like to donate to them, or find out more about supporting them or how to get involved, click here. Thank you to all our wonderful performers! We had great fun doing Finish the Lines too, of which Oliver Kennett came first place and won a highly-coveted Talking Tales badge.

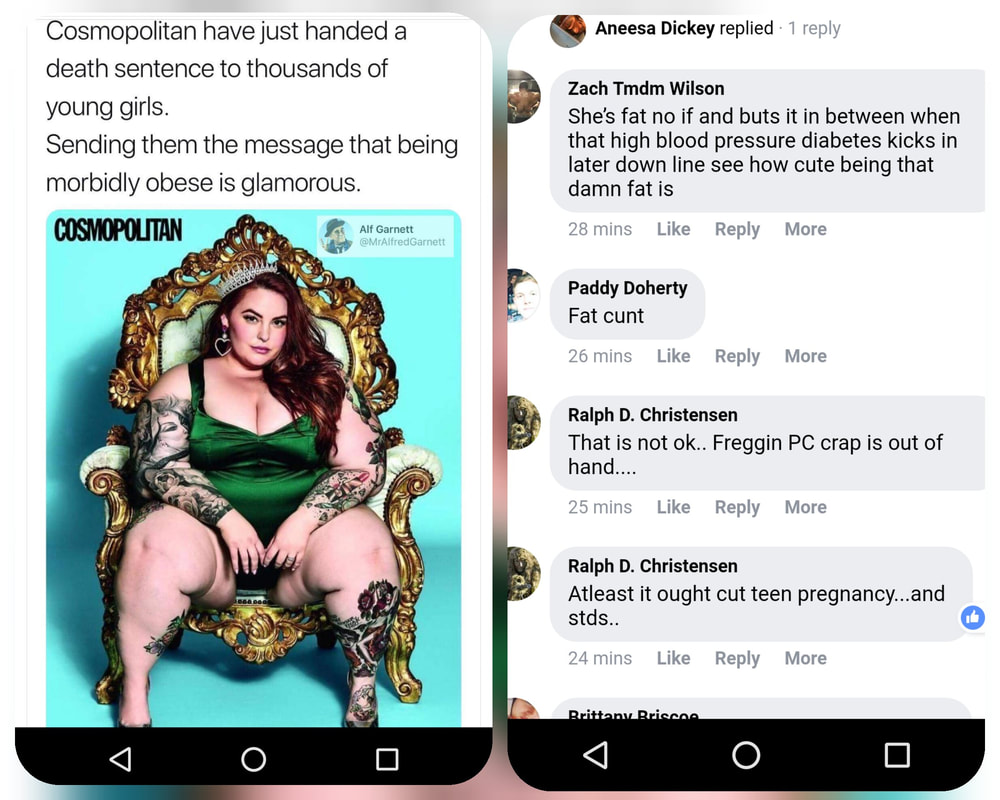

Thank you to our lovely audience for being so supportive, and thank you to Naomi Millard at The Wild Goose, and to Riyan, Val and the Arkbound team. For more information about Talking Tales and Stokes Croft writers, head to Chris Fielden’s website. Follow Talking Tales on Facebook and @SCWriting on Twitter for updates about future Talking Tales events. See you again soon! “Eating disorders can affect anyone of any shape or size.” “Eating disorders don’t discriminate.” You may have seen these statements online and most people would agree, right? But in reality, is this ethos really working in practice? When plus-size model Tess Holliday spoke out about having anorexia, people on social media lost their minds. It seemed impossible for people to comprehend someone in a larger body restricting their eating. After all, our society teaches “eat less, move more” as the simple equation for weight loss, so there was an assumption that she must be lying because if she was really restricting, how could she possibly still be fat? Of course this resulted in a lot of online trolling for Tess, and in turn the underlying reinforcement of the idea that only thin people can have restrictive eating disorders. When I say restrictive eating disorders, I’m referring to Anorexia and Bulimia. I think many people automatically picture a thin person, usually white, young and female, associated with these eating disorders. Often, fat people are associated with binge eating, but in reality thin people can binge and fat people can restrict. Many people aren’t familiar with the term OSFED - Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder – which is actually the most prevalent diagnostic category, because eating disorders don’t fit into tidy boxes like we expect them to. They are complex and nuanced; there’s no one reason someone develops an eating disorder (and all the many reasons are way too long to go into here!) Atypical Anorexia can come under this category, which is anorexia but at a “healthy” weight or above. The issue here is what is deemed as “healthy” is based on a flawed BMI system, created for white European men only, so it has been recognised as not an accurate predictor of health. There are also biases and assumptions of medical professionals, plus the limited resources on offer for eating disorder treatment, which often results in the “sickest” people getting help (i.e. thinnest). It’s a reactionary system, based on restoring someone's weight, though of course as eating disorders are to do with mental health, having a “healthy” weight does not mean the person has recovered. The short version of this is, the entire system is broken and people are not getting the help they need. (No disrespect to anyone working in the NHS, you’re just trying your best and I thank you for that.) My focus is usually on the societal and cultural aspects of eating disorders and disordered eating. I use the term “disordered eating” as that includes people struggling with eating who don’t fit the diagnosis criteria too – of which there are a lot! I’ve worked for eating disorder charities for about 5 years now and I continue learning more every day. I’ve heard more and more stories over the years from people who are frustrated, unheard, not believed, passed off, sent to weight management services or Slimming World, and judged because they don’t fit what an eating disorder “should” look like. All of this is causing an incredible amount of harm, discouraging people from seeking help. Even writing this here, I’m concerned about creating more fear. Do we warn people of this and risk putting them off asking for help? Or is warning them needed so they can be prepared? If you’re reading this and you’re considering reaching out for help with an eating problem, please still do – there are good people out there who can help you. If you don’t find one initially, see someone else. If you’re at a higher weight, a focus on anything to do with intentional weight loss will NOT be helpful so do set boundaries around this. You can refuse to be weighed too, or if they say they need to, tell them you do not want to know it. I tell healthcare providers that I do not want to know my BMI every time I visit and they are fine about that. I used to feel awkward about setting those boundaries, but with practice I now definitely don’t! Boundaries are self-care! My work has led me to learn so much about people’s relationship with food, and to continue reflecting on my own. Everyone has a body, and everyone needs to eat, so it’s really important for professionals to consider their own relationship with food and their body. Sadly there is a lot of weight stigma, bias and discrimination in the medical world, in the therapy world, and…well, THE WORLD. Nobody is immune to weight stigma and fatphobia. When I talk about weight biases in the medical profession I don’t blame individuals but rather recognise that we’ve all grown up in a society that tells us thin is good and fat is bad. This is why unpacking and challenging weight stigma and fatphobia is so important. On an individual basis, the fear people hold about being fat is both deeply understandable and so saddening to me. There is no shame in holding these views, there is no shame in chaotic eating, or having tried every diet in the world, or having purged, and there is certainly no shame in having difficult emotions around food and your body. We live in a world where this is created and normalised.

If you’re in a larger body and you’re embarrassed or ashamed that you just can’t seem to lose weight or keep it off, please know that this is not your fault. Many people’s bodies just aren’t naturally made to be thin, and the focus on thinness often drives disordered eating. Sadly, this focus on trying to do something which supposedly makes you “healthy” is likely the very thing negatively impacting your physical and mental health. The fear driven by narratives such as “the ob*sity epidemic” is very real and can make some people terrified that being fat will kill them. It will not; fat is not the killer but rather associated illnesses, plus the stress and trauma of living in a world that terrifies people into unhealthy behaviours such as yo-yo dieting, disordered eating, eating disorders, compulsive exercise, self-harm and more. This fear is not driving change, it’s only making things much, much worse. Fat is not an evil thing to be eradicated, but weight stigma, fatphobia and discrimination is extremely harmful and needs to stop. Many professionals will say that not all eating disorders are about body image and weight, which is true, however dieting is the biggest risk factor for an eating disorder. Dieting is often a result of wanting to lose weight to fit with the societal narrative of thinner equals healthier (not true), so it’s all rooted in weight stigma and fatphobia. Eating disorder professionals, medical professionals, therapists/counsellors, and other professionals working with anyone who may struggle with eating (which is A LOT of people) need to understand weight stigma and fatphobia for this reason. Many people are avoiding reaching out for help, being refused help, being wrongly diagnosed, and being judged for not being “thin enough” to have an eating disorder (sadly this is very common) so things need to change now. When I see statements like “eating disorders don’t discriminate” it makes me think about how eating disorders can often be seen as a disease that suddenly grips people, as if in a bubble from the rest of the world. Eating disorders are created from, and influenced by, a world full of inequality and discrimination. We cannot separate the person from the society and culture that has shaped them. The eating disorder treatment world is largely white, middle-class and able-bodied (professionals and researchers, and well as patients) which means this is the centred experience and everyone else is potentially left out. Also, recognising that fatphobia has roots in racism (see Sabrina Springs' work) and the impact of transphobia too, in the wider context of a capitalist system… the people who need help the most are sadly so often the ones being failed. Until we as a society can get our heads around the fact that most with people eating disorders are fat, AND that those people may also be black, trans, disabled, and/or a mix of identities, we will continue not to meet people’s needs. Saying “eating disorders don’t discriminate” is all well and good but sadly the systems designed to help and treat people often DO discriminate. I offer training for professionals on weight stigma and disordered eating, and I run Body Acceptance Workshops for people wanting to improve their body image. Find out more here. I am in the final stages of training as an Integrative Counsellor and I will be taking on clients in 2023. Please contact me to find out more. Body image problems affect lots of different people. It’s about how we see ourselves and perceive our bodies, but this is influenced by wider issues such as societal views, diet culture and inequalities. Body image isn’t something “silly” experienced only by teenage girls, nor is it something we can just “get over”. It’s not about vanity or being shallow. I could share a bunch of statistics about how many people don’t like their bodies but I think we all know… it’s a lot. I struggled my whole life with body image problems, mine mostly centering on weight but I’m aware that other people have body image issues that have nothing to do with weight or size. My work with individuals and in workshops however does tend to sway towards weight because it is such a big factor for so many people. Weight stigma is so prevalent in our society so it affects thin people too. Living in a larger body brings a lot of challenges but hating our bodies, being unkind to ourselves, and trying to change the way we look isn’t the solution (as much as it may really seem like it is!) Part of my own continued body image journey is being able to share my professional and lived experience with people, helping others understand body image on a deeper level and challenge perceptions of their bodies. I personally found that learning about wider societal expectations and inequalities, as well as past experiences and trauma, can help build an understanding as to why we struggle with body image, and this can help us be more compassionate to ourselves. I sometimes find that "body positivity" can be too fluffy, as much as it can be helpful for a lot of people. It just seemed unrealistic for me to pose in a bikini when I couldn't even wear a swimming costume without a big baggy t-shirt over the top for many years. "Body positivity" is unfortunately capitalised on by companies who have noticed its popularity, and by influencers and thin attractive people online who want to promote themselves. This takes it away from the very people who need the moment the most, e.g. fat, black, queer, disabled people and others who have faced discrimination and oppression. My body image approach involves taking a "big picture" view, understanding the societal and cultural issues surrounding how we see our bodies, including class, gender, disability, race, and more. Accepting our bodies can feel like a radical act in our society where capitalism needs us to be ashamed of our bodies in order to make money. So there can be such a lot to unpack when thinking about body image, which is why I offer workshops as well as one-to-one sessions. These can help you understand body image in more depth and help you move towards accepting your body. My next body image workshop is on Tuesday 6th September 2022 and is focused on “body acceptance” with a mix of educational content and exploration, along with guided meditations offered by meditation and reiki teacher Lesley Bailey (bios below). The online workshop is for anyone struggling with body image, or those wanting to support someone else, for professionals, or for anyone wanting to learn more about body image. It will include: ◦ Why exploring body image is important ◦ Causes of body image problems and the impact ◦ Lived experiences ◦ Weight stigma and dieting ◦ Myth-busting ◦ How we can help improve our relationship with our bodies ◦ How to support others with body image problems ◦ Practical tips and recommendations Find out more and book here.  About the hosts About Mel Ciavucco: I have been working for eating disorder charities for over 5 years and have a passion for understanding body image, eating distress and weight stigma. My own lived experience of struggling with body image, food and weight stigma plays a big part in my work as a trainer, I feel it goes hand-in-hand with my professional experience to bring enriching and inspiring workshops. I am a counsellor in training, due to qualify in 2023, and I also work on a Domestic Violence Perpetrator Program as a group facilitator. I run workshops on body image through First Steps ED, plus I have created comprehensive body image resources for them. I currently run creative writing workshops for people affected by homelessness too.  About Lesley Bailey: Lesley is a trained bereavement support worker, a senior administrator and a fundraiser for a local bereavement charity, as well as a Tropic Skincare Ambassador/Leader and a Reiki Master Teacher (Holistic Health Connection). Lesley says... "I began learning Reiki for myself back in 1998 until becoming a teacher and now meditation, grounding and being centred are an integral part of my own life and what I share with others. I am happy to have shared online meditation sessions throughout the pandemic but Reiki training, treatments and workshops are now available in person again. My love of natural skincare fits in beautifully with my ‘holistic head’ and led me to be an Independent Ambassador with Tropic Skincare nearly 9 years ago. It gives me the chance to find healthy and planet protective solutions for myself, for those struggling with skincare issues or for people who just want to make more mindful choices. I train and support my lovely team of Ambassadors to do the same. My work with Stafford & District Bereavement & Loss Support Service since 2014 is both humbling and inspiring. Experiencing losses myself, I understand the importance of having a safe, confidential and caring approach to the support needed at these difficult times. The fundraising aspect of my job is both a passion and a need in order to maintain this free service for our local people." Find Lesley on Facebook: www.facebook.com/lesley.bailey.58 with links to her Holistic Health Connection and Tropic Skincare pages. To find out more about other workshops click here. In 2020, I finished my Foundation Certificate in Counselling and Psychotherapy, then applied to go to university to continue my studies… but I’d been refused full student loans and was freaking out. I was mad about the industry (I still often am) and I wrote about my experiences here. I honestly thought I might ruin my career before I even started, I was so scared to share my thoughts. Now, two years on, thankfully I am on the degree I applied for after a nerve-racking “Compelling Personal Reasons” appeal to Student Finance. I used to hold counsellors up on a pedestal. The middle-aged, middle-class women I saw in my workplace were so different to me, I didn’t see how I could fit in. My Introductory course and Foundation Certificate was held in Bath where people laughed at the way I said “hug” (I’m from the Midlands but don’t have a particularly strong accent). It was as if some had never met a working-class person before. I struggled to speak up in group work, which I now think was partly about class and power but I didn’t have the words to explain that back then. Our short “diversity” session (a tick box exercise in my view) resulted in most people not saying a word for fear of getting something wrong. I realised I spent most of that year sitting in groups with very polite middle-class people wanting to be seen as the Nice Middle-Class Counsellor Who Treats Everyone Equally ™. The problem with “treating everyone equally” is that it ignores, minimises and denies people’s experiences (the opposite of what we should really be doing as counsellors!) If I’d tried to talk about class on my course, it would likely have been met by a very awkward quiet room again. No doubt there was also fatphobia in the mix too, something I passionately write and train people on, fat working-class people often getting the brunt of the blame for being a “burden on the NHS”. This is no disrespect to my course pals, they were lovely so I don’t want to point the finger at people but rather look at this on a systemic level. There are a lot of Nice Middle-Class Counsellors ™ doing great work in this industry, and the issue is not individual counsellors but the lack of intersectional approaches, diversity and inclusion from the top. When coming to the end of my Foundation Certificate I was asked why I wasn’t continuing at the same college (seen as one of the “gold standard” colleges) to which I told them I couldn’t afford it as they offered no financial help. The response I got was either “but you can pay by installments” (erm, where do they think that money is magically coming from?) and “we have a bursary”, which is for a person of colour. I am not a person of colour. That bursary should go to a person of colour, but did it? Being in Bath their answer is often, “it’s a white area” but a number of us were travelling from Bristol so that just seemed like another excuse. I got the sense that their “one bursary place” was more about them trying to be seen as a Good College For Nice Middle-Class Counsellors Who Treat Everyone Equally ™. There are lots of these colleges, so I am by no means singling this particular place out. These training establishments offer very good training, there’s no doubt, but only for a specific demographic. I have various privileges which meant I could train at the college in Bath, if only initially, but also I have managed to pay for all the *extras* of which there are a lot in counselling training! Insurance, membership body fees, supervision, personal therapy, transport costs… There’s a lot to take into account so even with student loans (which don’t cover much in terms of living costs) it’s A LOT, and that’s without factoring in having to work for free (for me in two different placements) to build up placement hours. This isn’t to put anyone off who wants to train to be a counsellor but this is the reality and is a large part of why the industry is so white and middle-class. Going to university in Newport (Wales) to do a degree in counselling was very, VERY different from the college in Bath – OBVIOUSLY. But for me, I was relieved to find myself in a place with a slightly more varied cohort, I say “slightly” because of course it’s still mostly women. I’ve always found it strange that an industry built on theories by mostly men is so dominated by women. Through speaking to various trainee counsellors at different training establishments, I’ve personally started to notice a theme; there can be a tendency for the universities/colleges to prepare trainees for lower-end wages in charities or agencies, whereas the private colleges (where you need to pay for it yourself as they don’t offer financial help/loans) set people up to go into private practice. One particular college I heard about doesn’t require students to do placements in agencies, but instead students go straight into PAID private practice. These students are the ones who can afford this privilege of course, so predominately white middle-class middle-aged people, who are being trained to immediately see mostly middle-class clients. These colleges, and students, may not talk about class, race or any other “difference” because they are being primed to stay in a middle-class bubble. These private colleges almost feel cult-like to me sometimes; they like you to see therapists and supervisors who have trained with them, then train to be supervisors with them, all “keeping it in the family” (cult), conveniently continuing to make more money out of students. These colleges don’t want working-class people, or people from marginalised groups, as they need to uphold this elitism. This is the same in many other industries of course; money comes first and they always make sure they maintain their power at the top. Of course the membership bodies mirror this too. It also means these colleges don’t have to change their curriculum to accommodate anyone “different” (I put this in quotation marks because what is “different” in this sense is only ever decided by those power). They can do their few hours of “difference and diversity” to tick a box, whilst sticking to the same old theories mostly written by middle-aged middle-class men. There are very few undergraduate degrees in counselling, like mine, in the UK. Most courses are at Master’s level, which is another major form of exclusion as you can’t do these courses unless you have a degree. My course is Integrative with a splash of Pluralism – a concept popularised by influential white middle-class men who tell us we should “prize diversity” (Cooper and Dryden, 2016). I’m glad be on a course with a little more “diversity” and to be learning more modern approaches to integrative therapy. My course had a online counselling module long before the pandemic – ahead of the game! Online counselling allows for more inclusion, for both counsellors and clients, so it’s important in my view to not rush back to “normal”. I think “normal” was old-fashioned, exclusionary and snobby, and I’m delighted to be part of a changing counselling industry that can offer more flexibility, adaptability and inclusion. Attendance and able-bodiedness has always been a focus in therapy (for both clients and counsellors), some courses insisting on 100% face-to-face attendance. Chronic illnesses, disabilities, social anxiety, work and family commitments, and many other factors can make it difficult for people to attend in-person, both counsellors and clients. Our training providers and membership bodies need to reflect that by valuing online learning (and counselling) and supporting students by meeting their needs. If there’s a silver lining of this awful pandemic, it’s an opportunity to work towards the kind of accessibility we should’ve already had in the industry.

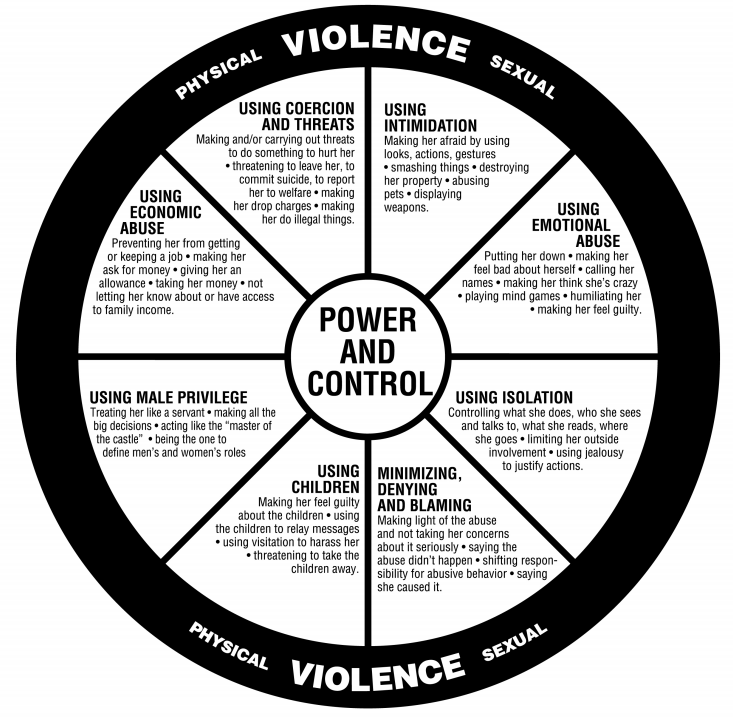

This year has taught me the importance of needing to be adaptable, creative and open-minded in the ways I offer counselling, and how this can still be done in a boundaried and ethical way. I continue to learn and remind myself of the natural neurodiversity amongst people and how everyone needs to communicate, learn and engage in different ways. I continue to keep learning and checking my biases about race, gender, sexuality, body size and appearance, neurodivergence, disability, and more, because this is so crucial for working ethically, and I always encourage other counsellors to do the same. I’m continually grateful for the privilege of being able to do this work with clients in my placements, in my job as a group facilitator, and running training and workshops. I’m sure my last year is about to fly by and I’ll be writing another follow-up blog before I know it as a qualified counsellor! I'm running an online body acceptance workshop on 13th July - find out more here! Content warning: domestic violence and abuse I work in domestic violence services and I’ve been horrified to see the public display of toxicity around the Johnny Depp and Amber Heard case. It’s EVERYWHERE. Memes, jokes, videos, GIFs, hashtags… mostly mocking Amber Heard, labelling her a “liar” and a “psychopath”. It scares me how much of an impact this has had, with such hatred on social media, showing the way our society sees domestic violence and abuse (DVA) and who we label “victims” and “perpetrators”. I’m not going to outline details of the case as there’s tons of information out there, I’m more interested in the impact on a social and cultural level. I work with perpetrators and am a trainee counsellor, so I have an interest in understanding how and why abuse happens. I take a big-picture approach when thinking about wider systems of power in which abusive relationships exist. I care more about the impact of this case on “normal” people, rather than debating the toxic details of two super-rich privileged celebrities. “Real” abuse It seems many people still view “real” domestic abuse as physical violence. There are many other forms of DVA, including emotional, financial, sexual etc, and lots of forms of coercion, manipulation and control. The breadth of DVA is shown in the power and control wheel later in this post (just one example, geared towards male perpetrator work). Physical violence is just one aspect of DVA, but all kinds of abuse are damaging and are traumatic. Perpetrators can use this idea of physical violence being the “worst” to position themselves as different to the “bad guys”. They reassure themselves by minimising and denying their behaviours, thinking they’re “not that bad”. They can say to themselves “but I’ve never laid a finger on her” or “I’d never hit a woman” to try to show they’re a ”good guy” and normalise their other abusive tendencies. This is to protect themselves from shame, a very difficult emotion to process, whilst allowing themselves to continue to feel the power and control of using their abusive behaviours. The memes of “real victims” side by side with Amber particularly upset and angered me, the “real victims” having bruises and black eyes and Amber looking fully made-up and beautiful. This idea of needing to have bruises or it doesn’t count only maintains our society’s limited views of DVA, stops victims speaking out, and colludes with perpetrators. The #metoo movement showed us how little women are believed, and often blamed. Examples include “what was she wearing?” and “was she drunk?” in relation to sexual abuse, and “why didn’t she just leave?” in relation to DVA. There have been many cases of men who have been convicted for abuse recently who are cast out by the general public immediately as monsters. But Johnny Depp (who has used abusive behaviour) is held up on a pedestal as one of the most beautiful men in the world. He’s rich, successful, loved and treasured as beloved characters in many people’s favourite films. The world was very quick to take his side as the victim, and Amber as the baddie, losing all nuance and treating it like a movie. This media circus completely dehumanised both of them, making it more about entertainment than a toxic relationship between two traumatised people. This case was not about who perpetrated the abuse, it was about Amber talking about her experiences. But it has been received by the public like a black and white, good vs bad, victim vs perpetrator case, and so now the perceived baddie must be punished. It almost feels barbaric and medieval, except now we use Twitter instead of throwing tomatoes at people in stocks. The social context Domestic abuse is always operating within wider systems of power and inequalities. It’s not just about the two individuals involved, it’s about the culture and society they’ve learnt from growing up, including gender expectations. We also live in a culture that elevates celebrities to a powerful untouchable level, especially when they’re very attractive. In a relationship, no two people are ever completely equal. The social context in heterosexual relationships can often mean that the man holds more privilege and power (although it may not feel like it to him). Privilege in this sense isn’t about your job or how much money you have, it means that there has traditionally and historically been more power afforded to men. I know many people think we’ve moved on from that now but we can’t just switch off hundreds of years of historical oppression. It’s still with us, under the surface. Johnny Depp is, was and always will be more powerful than Amber Heard. He is a rich, powerful man who holds an extremely large amount of privilege, entitlement and power. And now he’s becoming a poster boy for male victims in a society very quick to continually remind us that women lie and women are abusers too. Unfortunately, he’s more likely to be a poster boy for male perpetrators who want to paint themselves as victims, so I fear this won’t help male victims much at all. “But what about women?” Yes, women can use abusive behaviour - anyone can. But there are systems in our society that influence who becomes abusive and how, and cis-gender men are often the ones presenting as perpetrators, in terms of domestic abuse towards women but also violence towards other men and other violent crimes. I’m not saying this because I’m a man-hating feminist, I’m saying this because male violence is everywhere around us, all the time. How many more school shootings do we need before we talk about this? My work with perpetrators has always been with heterosexual men, and I’m often asked (and to be fair I asked this question too initially) “why are there no perpetrator interventions for women?” Overall, there is very little funding for perpetrator work (there’s barely enough for victim services) but if there was maybe there would be scope for different sorts of programs and interventions. So with the little funding there is, the largest group of perpetrators is the starting point, and that is men. I don’t think we’re very good as a society at holding men accountable without someone doing the “what-about-ery” and shouting “not all men”. Obviously, it’s not all men. But saying this just distracts from the problem. There are systems of power and entitlement in our society that mean that abusers, rapists, paedophiles, mass shooters and terrorists are often male. We just don’t talk about it. The more we distract from this, the more we’re moving away from being able to help and support victims. I personally believe we need to hold these men accountable without blaming and shaming them, to be able to help both them and victims. Being a “victim” also doesn’t mean being perfect and innocent, this is just a stereotypical idealistic view. Many victims fight back to protect themselves. Many are pushed to extremes and use violent behaviour. We need to understand the reasons for this and take an understanding and nuanced view of these dynamics. Masculinity standards and gender expectations Male perpetrator work is often psycho-educational and keeps women and children in mind whilst assisting the male perpetrator to challenge and change their own behaviour. The work can be based on unpacking messages around masculinity and gender expectations, and narratives around what women’s roles “should” be and what healthy relationships look like. It can be about looking into past experiences or traumas, and connecting the dots to current behaviours, without excusing them. Groups for men can be very powerful as they’ve often never been in spaces where they can build trust with other men, talk about emotions safely and be heard. In my experience, many male perpetrators don’t see themselves as being emotional people. Learnt behaviours from earlier in life and masculinity standards have meant they’ve been told not to cry or show any of the “weaker” emotions (associated with women). Instead, these emotions can then get funnelled into anger. Many people I’ve worked with don’t realise that anger is an emotion. They think they’re not “emotional people” when in fact they’re very emotional as they’re getting angry all the time. It’s a societal and cultural narrative that pushed them into only showing the “acceptable” emotions for a man – anger. A lot of work done with perpetrators is to help build awareness and shift their perceptions, joining the dots to understand their behaviour and understanding ways to manage and change it. In a relationship there are two people’s sets of dots, made up of gender and sexuality expectations, childhood experiences, trauma, attachment styles (how they relate to people and how they act in relationships) and how they regulate their emotions. It’s a bit like a jigsaw of all these aspects, trying to fit together. Sometimes they do fit, often it takes a lot of work, sometimes it’s a scattered mess, which is what I think Amber and Johnny are. In an ideal world, they just need to take their own separate jigsaw pieces off in opposite directions, tidy up their own bits, and move on. In other words, focus on healing themselves individually, outside of their toxic relationship. It’s unlikely this will happen unfortunately. People in difficult relationships often take patterns into the next one. In Johnny and Amber’s case, there seems to be a co-dependency, especially as it now seems Amber will be appealing the verdict. This whole case is an extension of the toxic power dynamics and abuse, and it looks like it’s not going to stop any time soon. Both are determined to be a victim and cannot walk away from each other it seems.

The impact on the general public The real victims of this are the people watching. It’s people stuck in abusive relationships who see their friends post memes on social media mocking Amber. It’s the general public who are being shown an inaccurate portrayal of abuse, and it’s men who will now be able to ignore/justify/defend their behaviour more than ever. This case will scare victims off speaking out about domestic abuse, even if they don’t name their abuser. It may keep people in toxic relationships, doubting themselves, thinking that they’re not a “real victim”. But the impact on perpetrators really concerns me too. There’s no doubt there will be a rise in defamation cases. Perpetrators often see themselves as victims, so this case will validate this for many. Any perpetrators who were starting to question their own behaviour, may now stop. They may think “maybe it was her all along” or “I knew she was lying”. Perpetrators engaging in interventions may drop out now as they have another reason to minimise and deny their behaviour. The repercussions of this very public, messy celebrity case is catastrophic for everyday people, be it victims, perpetrators and arguably most importantly – any children involved. What are we teaching the next generation? Seeing this unfold has affirmed to me that things are never black and white. Our society’s narrative is that there must be one victim and one perpetrator, but it’s way more nuanced than that. The Depp Vs Heard case wasn’t even about that but the public wanted a good vs evil battle. Amber, whether you think she is a perpetrator or not, does not deserve to have death threats and be hated in the way she had been. Abusers are not born evil, it is learnt behaviour influenced by our own societal views. In that sense, we help create perpetrators, but we can also help them change. It's all about the nuance Johnny Depp and Amber Heard have both perpetrated abuse, and this has been called “mutual abuse” but this does not mean it is equal. When a man holds this much power, it will never be equal. When women are silenced and not believed, I’m reminded that we have not yet reached gender equality. My plea is that people look at the bigger picture and see the larger systems of inequality, power and privilege involved. I would like people to understand that domestic abuse is not just about bruises or having “proof” but about power and control in more subtle ways. As an example, if a man puts his wife down for years, making digs about the way she looks, discourages her from seeing her friends, controls finances, makes decisions about their relationship based on what she “should” do as the woman and how he “should” act as the man… what happens when she snaps and physically pushes him or hits him? Is she the abuser and he’s the victim? We need to look beyond the physical violence and understand coercion, control and power. It’s never as simple as whoever proves they have bruises wins. My personal interest in working with perpetrators has always come from wanting to be part of a deeper solution, instead of just helping victims leave abusive relationships. Obviously a person’s safety is always the most important thing initially, but when we help people get out of toxic relationships, they can be drawn into others. Helping tackle to root of the power and control issues in perpetrators is crucial long-term work, and in turn helps victims and children. My empathy and compassion extend to perpetrators as I believe there are complex lifelong issues that lead to perpetrating abuse (childhood development, attachment etc, but this post is too long already to go into that!) Perpetrators are people who have learnt certain behaviours to be able to cope. I believe we can help them and help victims. But we can’t help anyone caught in toxic relationships if we keep these short-sighted societal views of domestic abuse. We can use this Depp vs Heard case as a learning curve, holding a mirror up to our society to show us that our views of domestic abuse must change if we are going to support victims and help the next generations. Freephone 24-Hour National Domestic Abuse Helpline: 0808 2000 247 or visit www.nationaldahelpline.org.uk (access live chat Mon-Fri 3-10pm)  TW: eating disorders, discussion of BMI and ob*sity Weight stigma isn’t only about the bullying, abuse and discrimination faced by fat people, it’s about wider societal systems of inequality and biases/assumptions which affect the way we think about eating disorders and disordered eating. Weight stigma and fatphobia is still present in eating disorder treatment and services, and is a barrier for so many people who need help. Not all eating disorders develop from wanting to lose weight or dieting… BUT dieting is a big risk factor for developing an eating disorder. Weight stigma affects everyone, just in different ways and to different extents. Even if a person doesn’t have an eating disorder based on trying to lose weight, their access to treatment is based on a system embedded in fatphobia and weight stigma. And for those who do develop an eating disorder from trying to lose weight or diet, weight stigma was likely a huge catalyst in that. The BMI chart Eating disorder treatment is known to have very little funding and limited resources, meaning that many people end up being told they’re “not thin enough” for help (see Hope Virgo’s fantastic campaign “Dump the Scales”). The BMI (Body Mass Index) chart is relied upon far more than it’s meant to be, despite the NICE guidelines saying not to use BMI to diagnose an eating disorder or to make decisions about treatment. The DSM-5 – the big boss American diagnostic people – list the BMI categories specifically in terms of what is “too thin” so the entire system is based on conflicting messages. Ultimately, it seems that healthcare professionals are pushed into a place of using BMI to decide who gets treatment (in restrictive eating disorders, mainly anorexia) because there’s only enough space for the very sickest people to get help. What that means is they’re waiting for someone’s eating disorder to get so bad that there are risks of serious medical complications before they can get help. This is reactionary and generally just really, really unhelpful… to say the least. The BMI scale was made in the 1830s by a mathematician and astronomer who based it on mainly European men – it was for general statistics, not a measure of individual health. So I think we can safely say that it isn’t exactly the best thing to be basing any kind of decisions/treatment on. When you add weight bias and eating disorder stereotypes (of people with anorexia being thin, white, young, female etc) this only makes the situation a whole lot worse. Weight bias We’ve all grown up in a world that tells us that thin equals beautiful, happy and successful, and health professions, GP’s therapists etc – as well as policymakers and people in charge – are not exempt from that. We hope that they’d address their own prejudices and biases during their training, and learn about eating disorders in the process, but this seemingly isn’t happening. I’ve heard too many stories of people who were told they couldn’t possibly have anorexia because they weren’t thin, and that somebody must binge eat because they’re fat. These kind of assumptions are due to weight biases and can be extremely harmful. In my experience as a trainee counsellor, we’ve barely talked about eating disorders on my training so far, so we certainly haven’t approached weight stigma (though I’ll be sure to find a way to bring in conversations about it of course!) GPs apparently only have a couple of hours of training on eating disorders, which is shocking. I’ve attended quite a lot of trainings/webinars/events about eating disorders and, no disrespect to any of them, but many of them were pretty basic. They just explain what the main eating disorders are, as if they’re rare diseases that are tragic flukes and completely out of our control. Yet eating disorders are deeply entwined with cultural and social ideas so we can all play a part in helping prevent them. This “othering” of eating disorders, seeing them as the opposite of ob*sity (they’re not) and disconnecting them from the normalised diet culture and fatphobic society we live in is not helping. Disordered eating is so normal in our society, many people likely can’t even tell if they have difficulties with food. Bullying and shame For people who have body image problems or eating issues due to trying to lose weight, many will have experienced bullying from a young age and may have encountered teachers, health professionals and other authority figures using shaming approaches to encourage weight loss. Kids can be mean, but they’re just exercising their power over people who seem different based on what they’re learning to be “normal” from their families, TV, films etc. When kids were mean to me at school I could try to shrug it off, but when adults and health professionals told me I had to lose weight, I had to do what I was told. It led to me trying to diet from a young age, trying to restrict my food, hating my body and blaming myself for being too fat. When it starts young, this stays with people for years and takes a long time to unpick. For me, it’s been many years of counselling, reading, learning and growing. It’s been 100% worth the effort though! People can often be well-meaning with their comments about dieting or weight loss. Maybe they’re just saying what they think is expected of them, making a joke or genuinely trying to help people feel better about themselves. However, this just reinforces diet culture and the idea that “thin is good”. Attempting to change our bodies to make ourselves feel better or happier is only a surface-level, short-term solution. Instead of changing our bodies, it’s about changing the way we think about our bodies. That’s why body image and eating problems should all be part of a broader mental health conversation. Fatphobia Eating disorders are often entwined with a fear of fatness (otherwise known as fatphobia). Many people working in eating disorders have a weight bias against fat people too – this isn’t to blame them as it’s something that is ingrained in our society. It’s systemic, throughout the medical profession and in our general culture, saturated in the system. So it’s nobody’s fault but it is our responsibility to recognise and challenge it in ourselves. Attempting to treat eating disorders in a system of fatphobia and weight stigma is hypocritical and counterproductive. Treatment within a broken system isn’t real treatment, it’s a Band-Aid at best. We are told we have an “ob*sity epidemic” whilst we in fact have a huge mental health crisis going on, throughout an actual pandemic (COVID). All the ways our government has tried to help the “ob*sity crisis” so far have been based on shaming and stigmatizing approaches (mainly involving blaming individuals and making people feel like crap about themselves) and it’s causing more harm than good. The focus needs to be on mental health and relationships with food. I firmly believe that eating disorders are a much bigger issue than we see on the surface. There are so many people who face barriers to treatment due to:

The list could go on. If we really knew the full scale of eating disorders, disordered eating and difficult relationships with food, we’d see the real epidemic. What can we do If you feel you’re struggling with any kind of body image or food-related problem, know that you can ask for help, even if you don’t think it’s serious or you don’t think it’s an eating disorder. Any kind of anxiety or distress around food or your body is important and you are deserving of help. For fat people especially – no body shape or size is more deserving of help, so go and take what you deserve! For people who are not affected by eating or body issues, it’d be helpful if you’d spend some time considering your own relationship with your body and your views of others. This is very important if you work in medical care or are a counsellor/therapist (and especially fellow trainees – hello!) Learn about weight stigma and eating disorders, consider your own experiences growing up and the narratives you heard about thinness, fatness and eating. Think about the rules you had around food (eg at the dinner table) and the way fat people have been treated at school, in workplaces and in their everyday lives. To everyone: consider shaking up your social media feeds – unfollow anyone who promotes dieting or thin ideals and follow diverse people instead. We need to hear more from people who are not the standard “norm” (mainly thin and white) to widen our views of the world and perceptions. As I hope I’ve demonstrated, the entire system is broken as it is based on fatphobia rooted in thin white bodies being the ideal. Anyone who doesn’t fit that (a LOT of people) is potentially be excluded, stigmatised and shamed. We must challenge the norms, the ideals and the stereotypes. Thanks for reading. Here are some resources which might be helpful: Anorexia & Bulimia Care Beat First Steps ED Beating Eating Disorders The National Centre for ED – excellent training for professionals NEDA – I highly recommend the roundtable discussion videos from fat, LGBT+ and black communities A note on the word ob*sity – many see this as stigmatizing language, hence the asterisk, as are terms like “ov*rwe*ght”, as they’re based on the BMI system which as explained is outdated, exclusionary and harmful to many people. Disclaimer: I wrote these blogs a long time ago! I'm leaving them up as I don't want to delete my journey and I think showing growth is important. But it means that some of my views, and some language I use, is now different so please be mindful of this. If you haven’t seen the beautifully painted bodies of the Naked Beach hosts, get yourself on All 4 and catch up now. The show follows three new contestants each week, all with different body image difficulties, as they go and hang out with a bunch of gorgeously diverse, naked body positive heroes. This, my friends, is how you bring body image issues to the forefront, and I couldn’t be happier! Naked Beach was devised by body image and mental health advocate Natasha Devon and Dr Keon West of Goldsmiths University of London. It’s based on research which shows that seeing diverse naked bodies can have a positive effect on your body image. This is certainly something that I’ve noticed in my personal body positive journey - when I filled my Instagram feed full of body positive people, I started to feel a lot more positive about my body. We see a lot of “perfect” bodies in films, TV, in magazines and on social media, and although we know it’s not real, we still see slim, young flawless bodies as the ideal. Thankfully, body positivity is growing fast and there’s an opportunity to see more diversity on social media now. But with these platforms giving everyone a voice, it’s just as easy to fall into the opposite - a bubble of unhealthy influences. Those pesky social media algorithms are just a little too good, showing you more of what it thinks you like. This can be a dangerous journey. I’ve experienced how easy it is to get bombarded with dieting adverts by simply visiting the Slimming World website once for research. Instagram knows I’m into yoga and so shows me adverts for leggings to make my bum look sexy. We can’t even exercise without having body standards thrust on us. At the time of writing, I’d just watched the second episode of Naked Beach. Not only is the show created by people who understand the nuances and difficulties of body image, they’ve also selected hosts who represent a wide range of bodies and are kind, enthusiastic, compassionate, and most importantly, understanding. The hosts have clearly been on their own body positive journeys and are keen to help others grow to accept their bodies too. The contestants watch the hosts jiggling about playing tennis, they draw their naked bodies and have one-on-one conversations, all to help encourage them out of their comfort zones. The hosts have such infectious, positive energies that it creates a safe space for them to take risks they might never have taken before, like wearing a swimsuit or exposing their stomach. It takes a lot of courage to show a part of your body you’ve thought of as disgusting for so long, that’s for sure. The show is described as a “controversial experiment” but why is it so controversial? In this article by Natasha Devon, she explains the backlash sparked due to it being shown before the watershed at 8pm. Natasha talks about how this is important because it’s intended to be a family show. It’s crucially important for young people to watch it if we want to help them grow up to be body confident, non-judgmental people. The beautiful body paint by Emma Cammack is an amazing way to allow these people to show their different body shapes and sizes while still keeping it modest for early evening TV. We British do have a tradition of being quite prudish on the surface but the truth is, pornography and sexualised images of women especially are everywhere – we’re just not talking about it. Millions of people seem to love Game of Thrones, which I’ve never watched but I hear it’s a pure cock and tits fest. When naked, glossy, “perfect” people are naked on TV it’s fine - but real people, “different” people, are seen as a bad influence. Beautiful, sexy bodies are acceptable because we’ve seen so much of them we now think it’s “normal”. This is why we need Naked Beach. We need to see differences so that we can see a wider perspective and stop trying to fit into a prescribed way of being. So to the parents worried about their kids watching Naked Beach - please let them. I would’ve loved to have seen this show as a child. This is a healthy way for them to see naked bodies because… and sorry to break it to you, but your kid is going to learn about nudity and sex from porn otherwise. Eeek. We desperately need shows like Naked Beach to show us how to respect people that aren’t “normal”. How to appreciate beauty in something without it having to be sexy. You can be beautiful no matter what you look like. It’s about changing the way you think, not trying to change your body, and it’s about questioning and calling out ugly behaviour. What we think of as “normal” has been steered by many years of seeing a certain version of beauty that’s been sold to us, mainly by companies who want to make money off our self-hatred. The ideal body is never going to be an easy one to attain because if it was, they wouldn’t make any money out of it. Diets are never going to work because if they did everybody would just be doing the one that worked and everyone would be thin. Naked Beach, without even saying these things, shows us different bodies and helps us experience the journey through the eyes of the contestants, to help us unlearn all the crap we’ve been taught about being attractive. I’ve worked on my body image issues a lot and I’m more accepting of the way I look, but I still have difficulties. During the first episode of Naked Beach I was thinking “there’s no way that I’d be getting naked on that beach” but by the end I was totally with them. I’d like to think if I was on the show I’d be easily throwing off that robe! The contestants have to stand in front of a mirror for twenty minutes every night – it’s a form of exposure therapy. Twenty minutes! That’s a long time. So I decided to give it a go, and it was okay but I got bored after about ten minutes! I still don’t wear a bikini when I go to the beach, but I realise that’s not a failure. A bikini isn't the goal of body acceptance, and I know I don't have to love myself right now. It's a process. Compared to how I was – wearing a baggy t-shirt over my swimming costume and refusing to take it off – I’m doing okay. It’s a big jump to go from hating your body to being in a bikini so it’s still a big achievement just to say “my body is okay.” And if you’re not ready to say that, then just know that you’re still on the right track. Just keep reading and watching body positive stuff. I’d love more Naked Beach! Sadly there were not many episodes. I bet the hosts had some amazing stories to tell. Hearing somebody else’s body positive journey can be so empowering: what they did, what they learnt, how they pushed themselves out of their comfort zone. I think what we see in the show is just the tip of the iceberg, and it wouldn’t surprise me if there were conversations late into the night about the nature of the beauty industry, the media and the companies that make money off us hating ourselves. How rigid gender roles have caused various body image issues for people of all genders, as well as causing major mental health problems for not looking “normal” and fitting into the bullshit rules of what it means to be a "man" or a "woman". People wanting to help their body positive outlook will be drawn to this show, but it’s important for people who don’t have body image issues to watch it too. As much as it’s a necessity to help people struggling with their own body image problems, we need to address the underlying issues - discrimination and stigma. I believe that you can transform the way that you think, but you need to be willing and able to give it a go. The reason why it becomes difficult to live in a body that is “different” is because of weight stigma, ableism, racism etc in our society. I grew up thinking fat was ugly and unhealthy but I’ve spent a lot of time reading and learning and I now know that’s not true. My values and options have changed and they will continue to change. Major mental health problems are caused by judgemental attitudes towards people who are “different” (which is a lot of people) and we need to start taking responsibility for this as a society. There can be a lack of empathy from people who don’t experience body image issues – they’ve not had to experience what we’ve been through. Naked Beach could help them see the world from the eyes of somebody who has always been judged for how they look. It may change some judgemental attitudes, or it may not, but it’s worth a shot. I really hope that people will give it a chance and be open-minded enough without saying any of the usual crap like “they’re glorifying obesity”. They’re really not. In fact, two of the contestants so far were inspired to start working out again since they felt better about their bodies! Body positivity does not "glorify ob*sity", it instead lets us know that you don't need to hate your body. When people start to respect their bodies, they are more likely to treat them well. So Naked Beach as an “experiment” isn’t necessarily on the contestants, they already know from research that this kind of exposure to diverse naked people works. The real experiment is on us, the viewers. Can we finally start to create a kind of society where we challenge our preconceptions and start to accept people’s natural diversity? Watch Naked Beach on All 4 here.