|

Skinny jabs. Weight loss injections. The new miracle drugs to “tackle the ob*sity crisis” once and for all. Drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy are being hailed as wonder drugs. Oprah raves about weight loss drugs and says “ob*sity is a disease” so it’s not about willpower. This apparently can help get rid of weight stigma…by reinforcing weight loss and thin ideals? This doesn’t make much sense to me. “Ob*sity” is not a disease, nor a behaviour or an eating disorder. It’s a body size measure and there is wide range of people of varying degrees of health within that bracket. It’s not something that needs fixing. However, I understand that many people feel unhappy in themselves and want to make changes, though sadly this often becomes about making themselves smaller using any means possible. I’m not against people who choose to take weight loss intentions, in the same way that I’m not anti people who diet. When I use the term “anti-diet” I mean I stand against diet culture, the thin ideal and weight stigma/biases in our society as these are harmful to so many people. It’s important to make an informed choice, and how can we really do that when we are swimming in diet culture narratives? The decision to take weight loss drugs needs to be based on reliable information, and should you choose to go ahead, it needs to be done safely, through the correct channels and with plenty of support before and after. Having counselling before can help you explore your relationship with food and your body, as it may be that you’re experiencing disordered eating or negative body image thoughts. If this is the case, taking weight loss injections will not help – it will likely only drive the thoughts and feelings that underpin your relationship with food and make things worse. Weight loss injections: what are they and how do they work? Weight injections are for people in higher BMI (Body Mass Index) categories, and in the UK they are usually available through a referral to a weight management service. It’s meant to be more of a last resort, like weight loss surgeries, and only available for those who “really need it” i.e. higher weights. I don’t mention specific weights as this can be triggering and further reinforces weight stigma. BMI itself is very outdated and not fit for purpose – you can learn more about that in this article by Aubrey Gordon aka Your Fat Friend. Weight loss injections work by making people feel full for longer. The idea is, if you’re less hungry, you’ll eat less and that means you’ll lose weight. This may work in the short term whilst you’re on the medication, but when you come off it you will gain it back. However, eating less doesn’t necessarily equal thinness – lots of people in larger bodies have likely tried eating less, perhaps having tried every diet under the sun, and are not thin (if diets “worked” wouldn’t everyone be thin, right?) Even if people do lose weight they may not be thin, as for many people thinness is not just possible. Our weight is decided by many factors and genetics is a big part of that. If people can be “naturally slim” then people can also be “naturally fat”. Your body will work hard to keep you at a “set point range”, your body’s comfortable weight range, in a similar way to how our bodies regulate our temperature and our need to go to the toilet. Our bodies are clever and we should trust them but due to diet culture, many of us have lost that trust sadly. Do weight loss injections "work"? The long-term “success” of weight loss injections is not yet known as research has not been going long enough to be able to adequately tell. Whilst some diets and weight loss interventions can result in weight loss in the short-term weight is often gained back in the long run. In the UK, weight loss injections are only prescribed on the NHS for a maximum of 2 years, and one study has shown that people regain two-thirds of the lost weight within two years of stopping. Short-term side effects include headaches, nausea, sickness, diarrhoea, acid reflux, constipation and more. Long-term side effects of staying on weight loss injections for many years aren’t yet known, and due to fears of weight regain it is concerning how many people may try to stay on them for life. These drugs were first intended for people with diabetes, so there have been shortages recently since its growing popularity for weight loss. Celebrities, and thinner people generally, are using it to “drop those last few pounds”, many of whom can afford to pay for it privately. Purchasing weight loss injections can be expensive plus there are risks of purchasing them online. The risks of buying weight loss injections In the documentary, “The truth about skinny jabs” with Anna Richardson, she visits some private clinics in London where they were happy to prescribe weight loss injections, without even taking any health markers, and despite her not being fat. They did so with a hefty bill of course. Anna also experiments with buying weight loss injections online, which she does with alarming ease. The risks of this are many; you can’t trust what’s in them, you might get ripped off or scammed, and anyone young or vulnerable could potentially buy them including those with eating disorders. This is a very dangerous way of accessing these drugs, you really don’t know what you’re getting. People on social media also target people for sales and these are often scammers. If you decide to take weight loss injections please do so through the proper medical channels, and if you do not meet the criteria for them, do not take them. Body shame is big money The idea that being thinner equals happier, healthier and more respectable is the entire basis of diet culture. Companies thrive off the body shame people experience when they think they’re not thin enough (even if they’re not fat). A common myth is that people at higher weights are so because they eat too much. This idea is way too simplistic, it is not as basic as “calories in, calories out”. When it is seen as individual responsibility and just an easy “choice” to lose weight, it’s putting more blame and shame on people. Even if two people of different sizes ate exactly the same they could be completely different sizes. The idea that everyone has the ability to be thin, and that thinner is better, causes so much harm in our society and is a major driver for disordered eating. “The best-known environmental contributor to the development of eating disorders is the sociocultural idealization of thinness.” - NEDA Using weight loss injections only reinforces the thin ideal and the fear of weight gain and increases the harmful experiences of fatphobia and weight stigma. These drugs do not help people with their health behaviours, or other aspects associated with better health like reducing stress and better sleep. Weight loss injections offer the same enticing dieting promise that thinner equals happier and healthier, which is simply just not true. Ultimately, in the same way that every other new diet culture fad says they are “the one” that finally makes everyone thin, they’re not. There are lots of fat people in the world and we will always still be here. Eating disorders There are sadly too many people who are overlooked for having an eating disorder due to their body size. Many people may not recognise that their eating is “disordered” as diet culture has normalised restrictive eating, over-exercise and the pursuit of thinness “no matter what”. Due to myths and stereotypes about eating disorders, people often assume you need to be thin to have one, when in fact most people with eating disorders are not underweight. With disordered eating labels such as Atypical Anorexia (Anorexia but not at a low weight) and Orthorexia (a preoccupation with “healthy” or “clean” eating), the lines between eating disorders, dieting and “healthy eating” are becoming increasingly blurred. This, coupled with weight stigma, means that people are often prescribed/recommended weight loss interventions when this will likely only drive the disordered eating. A person who has struggled for a long time with dieting or disordered eating is not going to be helped by yet another thing that attempts to make them thin. The diet cycle thrives off shame, and every time an intervention fails, people blame themselves or their lack of willpower, when it’s not their fault at all. Diets are made to keep you coming back, diet companies wouldn’t make any money otherwise. Weight loss drugs, manufactured by big pharmaceutical companies, are also made so you stay on them, potentially costing you a fortune and taking on the unknown long-term risks as well as short-term side effects. Diet companies and big pharma do not care about your health. It’s all about money and they profit big time off your body shame. In conclusion… If you’re concerned about your health or have fears and anxieties about your weight, please consider exploring your relationship with food and yourself before any kind of weight loss attempts or drugs. Counselling can help, as well as learning more about disordered eating, diet culture, and body acceptance and intuitive eating. Eating and body image issues can have deeper food causes and influences which will not be helped with weight loss attempts, this just keeps the cycle going. To break the cycle and make lasting changes, a deeper exploration is needed. I offer counselling sessions online, please check out my counselling page for more info. I also offer workshops on disordered eating, body image and weight stigma, please check out my workshops page for more information.

0 Comments

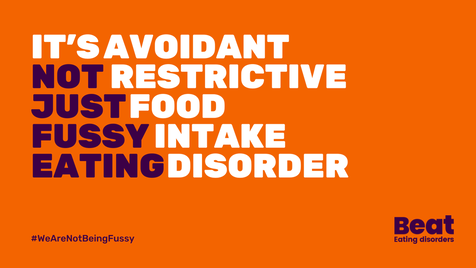

A couple of years ago I wrote an initial reflection on working with perpetrators of domestic abuse when I was relatively new to the work. Since then, sadly the service has closed as the funding ended. This is not uncommon in this field; victim services are barely funded enough so perpetrator services can be a hard sell. So, given this sad ending, I wanted to reflect on this amazing work and what I’ve learned about working with perpetrators, and about what we need to do as a society to help men. Due to the nature of this work, no names or identifying information about the organisation or individual involved will be used. I’m a counsellor in private practice but I worked three days per week for a domestic abuse charity, doing group and 1:1 work on a perpetrator programme. I started as a group facilitator and then I got more involved, doing assessments and also doing one-to-one Behaviour Change sessions. I was surprised that I could even do this work, I’d always been drawn to it but thought I was just being naïve at first! I remember when I first started training to be a counsellor, we were asked if there were any clients we wouldn’t want to work with. Some of my peers said offenders/perpetrators (especially those who had harmed children) and as much as I respected their choice, I became aware that I was one of the few who particularly wanted to work with these groups. They are the most stigmatized and shamed, and who arguably may need us the most. I knew if I could get into this work somehow, I definitely should. It felt so important. I thought the concept of perpetrator programmes was great; as well as helping people leave abusive relationships, we had an opportunity to go to the root of the problem and help break the cycle. It feels like our domestic abuse victim services are just firefighting at times, doing the very best they can do with the funding and resources available. Domestic abuse is about patterns of power and control, so when an abusive relationship ends, there’s always a risk that either person could enter into another abusive relationship. These are generational cycles which many people don't realise that they're in. I wanted to help break the cycles and help the ripple effect, ultimately to help partners, future partners, children and grandchildren be safer too. My first observation of a perpetrator group was eye-opening. I was struck by the level of openness and honesty from the group members. I also admired the challenges offered by the facilitators, whilst holding a non-judgmental and compassionate space. I knew it was for me instantly. I was worried I might be scared and would want to literally run out of the room, but something in me just felt right. For somebody who was a timid child being told by many to “be more assertive”, I surprised myself by becoming a confident, challenging facilitator! The most important part of this work was the support from the team. My co-workers, supervisor and manager made this possible; it’s crucial to have a good team to be able to “hold” this work and manage risk. I’ve always been fascinated by why people do what they do. I don’t believe that people are just “bad” or are born “evil” or “monsters”, it’s just not possible. People who hurt others have often been hurt themselves. They may have had difficult relationships, or sometimes struggle to have meaningful relationships at all. There can be attachment and child development issues, past abuse and trauma. The complexities and nuances of what makes a person harm others are complicated and different person-to-person, but everyone deserves the chance to be heard and shown respect and compassion. The perpetrator programme offered this balance of being challenged and held accountable, whilst being strengths-based, compassionate and empathic. Many perpetrator programmes are just for cis-gendered men, but this doesn’t mean other people aren’t abusive of course. There needs to be more provision for programmes for a range of genders, sexualities and relationship arrangements. However, there is barely enough for men at the moment, and men are the most common perpetrators of abuse. This can be a confronting thing to talk about, especially online, as there can be backlash, defensiveness and “what-about-ery”, e.g. “but what about all the men who are abused?” This is a valid point, but can often be used to derail the conversation about male violence. We need to name it to help solve the problem. In my view, patriarchal norms and expectations harm everyone. As a woman, I feel I was socialised to adhere to the male gaze, meaning I needed to try my best to be attractive to men and give them what they wanted. My self-worth was wrapped up in what men thought of me. I gave their opinion more worth than my own, about my own body! These messages came to me from films, TV, family, friends…it was the water I swam in so I never questioned it. It was just normal. When I started learning about feminism later, I had a lot of unpacking to do. I realised that I upheld unrealistic standards of myself, but also, I was helping uphold masculinity standards too. Masculinity comes with its expectations, norms and demands. On the programme we would explore the “man box”, all the things that keep men trapped in the expectations of their gender, and the consequences for stepping outside the box. The pressures and expectations can include, not being “emotional”, not crying, being tall and muscular, being “the provider”, not showing vulnerability etc. Sadly, this meant the men often had learnt to push down their emotions, as they were unacceptable. Many had never learnt how to talk about emotions and never had that modelled for them. Part of the magic of group work is having the space to talk to each other, which in turn helps model vulnerability and provides practice in communicating about emotions. It’s an experiential, powerful intervention, as well as the psychoeducation, exercises and discussion on the programme. These together, the relational group dynamics and the programme topics and themes each session, created an intense but very impactful intervention. It felt like such a gift and a privilege to do this work and witness this. As facilitators, our strength is in being compassionate but challenging. Trying to hold somebody accountable by making them feel belittled or told off is just not going to work. It triggers the shame that so many of these men have deep down, that is so hard to let out, let alone speak about. Their shame can feel too much, so it’s often the cause of defensive behaviours. When you’re not used to being vulnerable, it can feel terrifying. We needed to help hold this shame whilst they explored and worked on themselves and their behaviours. We often talked about the “pit of shit” (was “shame” but “shit” became more fun), and how getting out of it required them to clamber out onto the path of accountability. But it’s hard to climb out whilst stuck in the sticky, muddy shame, especially for those with low confidence and self-esteem. It brings a paradox for some who would consider these men not to be deserving of feeling better about themselves, but this is the very thing needed to climb out of the pit and take responsibility. We loved an iceberg on the programme. We’d draw the angry behaviours at the top (i.e. what you can see, e.g. shouting, slamming doors), with the underlying emotions below the surface, e.g. fear, vulnerability, shame. A theme I often noticed was jealousy. This often linked with underlying feelings of insecurity and low self-esteem. The controlling behaviours stemmed from the jealously and inadequacy, and fear of abandonment. This could have been impacted by experiences in previous relationships and likely caregiver relationships in early childhood. An insecure attachment can be a common factor with some men on these programmes, in my experience. Entitlement, in the context of being entitled to women’s bodies, may be more likely to stem from societal and cultural influences which tell men they have a right to women’s bodies. We see this a lot in the “manosphere” (men’s rights activists, incels etc) which many might argue is getting worse now we are in the “Andrew Tate era”. It seems the idea of being an “alpha” is becoming important again (which to me is men literally putting themselves in the constraints of the man box), and with this comes the idea of power over women (and other men). Ultimately, I believe so much of this is rooted in fear of losing power. Women and trans/non-binary people are taking up more space now and having more power, and this is seen as a threat to men. It’s not of course, it’s an opportunity for us to dismantle patriarchal and traditional gender norms and expectations, which would help us all. What it means to be “masculine” needs more flexibility and more empathy. We need positive male role models who can help other men, standing against harmful behaviour but in a way that doesn’t shame them. We need media literacy for children and young people to help understand and reduce the risk of online grooming into the “manosphere” and ethical use of pornography. We need women to stop upholding gender expectations on men too and support them to be able to feel safe to show emotions. We need to stop the increasing transphobia and make it safe for people to be themselves. We need better representation of vulnerable men on TV and in films. We need to stop normalising abusive and controlling behaviours in the media. We, as a society, have a lot of work to do. But we also need to have compassion and remember the humanity in people, and believe that some people are absolutely able to change. I’ve seen these changes happen; men have become better fathers, they’re able to understand themselves and their behaviours so much better, and they now model to their kids that it’s OK to be vulnerable, and how to take accountability. We need to keep breaking these cycles for generations to come. I did a talk with Online Events about this too, if you’d like to find out more or purchase a recording CLICK HERE. I also offer other workshops, please check out my workshops page for what’s coming up. Body image problems affect lots of different people. We live in an appearance-centred society, but it’s not just about vanity or being shallow. Body image issues aren’t something “silly” experienced by teenage girls, nor are they something we can just “get over”. Body image is partly about how we see ourselves and perceive our bodies, but this is influenced by wider issues such as societal views, diet culture, inequalities, power dynamics and discrimination. I struggled for many years, most of my life, with body image problems. For me this centred on weight but I’m aware that other people have body image issues that have nothing to do with weight or size. My work with individuals and in workshops however does sway toward weight because it is such a big factor for so many people. Weight stigma is so prevalent in our society; it can affect people of various sizes, though people at higher weights face discrimination and many more challenges in daily life. Hating our bodies, being unkind to ourselves and trying to change the way we look isn’t the solution. Punishing ourselves only makes it worse. As a counsellor and trainer with lived experience of body image problems, I am passionate about helping others understand body image on a deeper level, to enable them to challenge their perceptions, assumptions and internalised fatphobia. I personally found that learning about wider societal expectations and inequalities, as well as past experiences and trauma, can help build an understanding of why we struggle with body image. Knowing all of this can help us be more compassionate to ourselves, and others. I find that "body positivity" can be too fluffy. As much as it can be helpful for some people, it can just be yet another pressure; the pressure to “love yourself”, which is a big jump if you’ve hated your body for years. For me, it just seemed unrealistic to jiggle around in a bikini like the people I saw on Instagram when I couldn't even wear a swimming costume without a big baggy t-shirt over it for many years. "Body positivity" has unfortunately been capitalised on by companies who have noticed its popularity, and by influencers and thin (often white) attractive people online who want to promote themselves. Unfortunately, this has taken the movement away from the very people who need it the moment the most; fat, black, queer, disabled people and others who have faced discrimination and oppression. My body image approach involves taking a "big picture" view, understanding the societal and cultural issues surrounding how we see our bodies, including class, gender, disability, race, and more. Accepting our bodies can feel like a radical act in our society where capitalism needs us to be ashamed of our bodies in order to make money. Accepting living in a larger body can be incredibly difficult for people, given the weight stigma and fatphobia they may face. Self-worth is so often tied up in body image. For me, healing came from understanding experiences in childhood which impacted my confidence and self-esteem. Trauma, bad experiences, bullying and attachment difficulties can all play a part in how you view yourself and your body. Gender expectations also play a big part, and how comfortable you feel in your identity. Neurodivergence, such as autism and ADHD, can also impact how you view your body, and how your body feels. I’ve heard many people talk about not fitting in and feeling like they don’t belong, which in itself is a very difficult way to grow up and can result in anxiety and social isolation. Race, culture, disability, chronic health conditions, visible “differences” and much more affect body image. When the dominant beauty standard (here in the UK) is thin, white, young, able-bodied and “normal”, anyone outside of that can be deemed “different”. We could speculate that in fact, all those “different” people would make a majority, though this is more about power held by dominant groups in our society and the “othering” which maintains that power. If you’re struggling with body image, you don’t have to “love” your body right now, but you could start to explore what makes you feel the way you do about your body. Having counselling may help – if you’re interested in finding out more about my counselling service click here. For professionals, looking at the whole person and intersecting identities, and the context of their life, is so important to understand body image. But the starting point is looking at your own relationship with your own body, and the influences on how you see others’ bodies too. If you’re interested in finding out more about my training on disordered eating, body image and weight stigma, click here. It's Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2024, and BEAT's theme is ARFID (Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder), which is what I'm going to attempt to write about today. I'm going to caveat this with I'm not an expert, but I don't think many people are given that there’s very little research, literature or training on ARFID. What there is tends to be about children and young people, mainly from a White Western perspective. So I'm writing this based on having worked with some people with ARFID (adults only) in my counselling practice, and from my own experiences. It’s important to note, that for people who do not have a diagnosis of ARFID (or any other eating disorder), your struggle is still absolutely valid and you are still worthy of help and support. What is ARFID? ARFID - Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder – is a lesser-known eating disorder, categorized in the 5th edition of the DSM-5 (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). ARFID is described as an “eating or feeding disturbance” which may include sensory sensitivity, fear of aversive consequences of eating, or lack of interest in eating. This can manifest in various ways, such as avoiding certain food textures, colours, or smells, experiencing a lack of appetite, or having a limited range of acceptable or safe foods. My personal experiences I describe my own experiences usually as "disordered eating" as I've fleeted around different difficulties in my life but never been diagnosed with an eating disorder. I never considered there was even an issue, until I started learning more about eating disorders, and learnt about the influence of diet culture and weight stigma in my life. When I learnt about ARFID, I could definitely relate with some of my experiences of being fearful of foods. I was fortunate enough to travel quite a long time in my 20’s, but was not so great on my guts. I had food poisoning numerous times and became anxious about what I could eat as almost everything seemed to make me feel nauseous, bloated and have a bad stomach. I saw various professionals - medical and holistic - many of whom seemed to want to tell me what not to eat. I did various elimination diets and nothing worked. I just got gradually more scared of what to eat. I even cut out tomatoes for a while, which for an avid pasta and pizza eater was really no good! My poor stomach has taken the brunt of most things in my life, emotionally and physically, which I manage on an ongoing basis still though it is much better now. It took me many years to start building up what I could eat again. It didn’t start with challenging myself to eat more foods, it started with finding more routine and stability when I moved back to the UK. I started having counselling, doing yoga and building up my relationship with myself, and food. I also had a lot of diet culture stuff I was trying to unpack, which was an added complexity. I didn't hate my body anymore but I certainly didn't love it. I was starting to be a little kinder to it at least. I felt brave enough gradually to try new things, but it’s scary when you’ve had bad experiences with food and it’s made you ill. I wanted to have variation in my eating and to reduce worrying about food, and some of that meant challenging diet culture narratives I’d picked up growing up, and societal ideas about “healthy” eating. I aimed for more of an intuitive eating approach and tried to get more in touch with my body, hunger signals and focus on what my body needs and how it felt instead of external influences. Like many people who have struggled with eating, I have foods and places I feel safer with, and I like to know what’s on the menu at places I eat beforehand. “Recovery” means different things to different people, there is no one-size-fits-all because everyone’s experiences are so nuanced and complex, but sometimes it just means managing a little better. Norms and expectations I feel way more at ease with food now, but I will never forget what the fear of eating feels like. I know what it's like to feel anxious about eating out, and eating at other people's houses. To be scared that there won't be anything for you to eat, and that people will judge you for being picky or difficult. To feel like you can’t eat like a normal person. It can be incredibly shaming to feel like the odd one out, that you're being too dramatic, and is easy to blame yourself for these things. This has a huge impact on your life; socially, at work, career choices etc. It can really hold you back. As a counsellor now working with eating disorders and disordered eating, I feel my lived experiences are important and beneficial in this work. Some people with eating difficulties will have experienced things very differently, but I still have some insight and I understand the turmoil, frustration, shame and various other underlying feelings associated with eating disorders. The main thing I’d like to let people know is that your struggle is valid, it’s a tough way to live, it is definitely not your fault and you absolutely do deserve help and support.

Normal eating? So what even is normal eating anyway and who makes the rules? Spoiler… “normal” eating doesn’t exist. Diet culture has a lot to answer for, but we also start learning about food from the moment we're born. Early childhood experiences and narratives around food can create templates which run through your whole life. We learn how to eat from others, which is heavily influenced by culture and society and “norms” can become ingrained. Some people, like myself, will learn that there are “good and bad foods” and that healthy equals being thin and fat is bad. As babies we cry and get fed, but then everything changes once we’re faced with a dinner table; there are rules and expectations. I am aware I’m speaking from the position of being a white British person, so only from one limited cultural perspective, but I was taught about how meals had to be “balanced” to be healthy and to eat 5-a-day and all the other generic stuff. Even in the past few years, I’ve been handed “how to eat” type leaflets from medical professionals that were literally from the 80’s. It’s just not realistic to have one “right” way of eating, our bodies are so different. It also assumes the “right” way is based on White Western approaches to eating, assuming this is the “normal” way. It is not. We all need to find our own normal and not feel ashamed for this. Neurodiversity We can’t talk about ARFID, or any other eating disorder, without talking about neurodiversity. I use this term here to refer to the natural differences in the way everybody thinks and processes information. Through my own practice I’ve learnt the importance of looking through a neurodiverse, and intersectional, lens. Even working with people who are neurotypical there are benefits to this, as everyone has different communication and learning preferences. With ARFID, there can be sensory sensitives in many people, meaning that different textures of food, mix of foods, and variance of foods can make life very tricky. Think about how much fruit and veg can vary in texture (and taste) from day to day! There is no consistency, therefore no safety, in those foods at all, but with some crackers or a packet of crisps, it’s the same each time. For neurodivergent people (which in this sense I’m referring to autism and ADHD mainly), there can be a pressure to “mask” and try to “fit in”, which may mean added pressures and anxieties around eating “normally”. The idea that we have to help people fit in with what we perceive as a “norm” (which is often a position of privilege) is not acceptable, especially in the case of neurodivergent people and those with disabilities. The world needs to accommodate, not reinforce a “norm” which is inaccessible for many. This again can lead to self-blame and shame. The same is true for eating – the “healthy” and “right” way of eating is too limited to accommodate everyone, and to enforce this is potentially harmful to people. For some people, the pressure, expectations and feelings of not being “normal”, and self-criticism and shame that come from this, are arguably the issue more than the food they don’t want to eat. The pressure from others, especially on children struggling to eat (who have little autonomy and choice) can exacerbate the situation, which is often due to understandable concern for their loved one but is underpinned by “norms” and expectations of what they think they “should” eat. Acceptance Many people with ARFID want help to be able to widen their food options, reduce anxiety around food and live an easier life, so I’m not suggesting that people just accept the limitations as that’s not going to be realistic. But I feel it can be helpful to start building self-acceptance and reducing critical thoughts as this will help recovery and healing. Putting in boundaries with others, and unlearning some narratives around food might be important too. Safety is such a big part of this, in the sense that food needs to feel safe to eat, but also places and people need to feel safe too. For people with ARFID seeking help, they may be nervous about seeing professionals in case they are forced to eat, or met with judgement or dismissal. The main issue with ARFID is that it’s so different for everyone, so there are no specific ways to help. It would involve working on a case-by-case basis, in a person-centred way. It is important that the person feels they’re not being judged, but that they have control and can make choices for themselves. There are currently no evidence-based treatment recommendations for ARFID but some treatment options in the NHS can involve Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, or family therapy for young people, with nutritional support too. For many people, it may be difficult to get a diagnosis (or they may not feel safe to go to their GP in the first place) so they may opt to seek help privately. I work in an Integrative way, with a person-centred foundation, meaning I incorporate different theories and approaches but I am collaborative and adaptable to suit clients’ needs. This is not a “how to work with ARFID” list but there are some approaches which might be helpful:

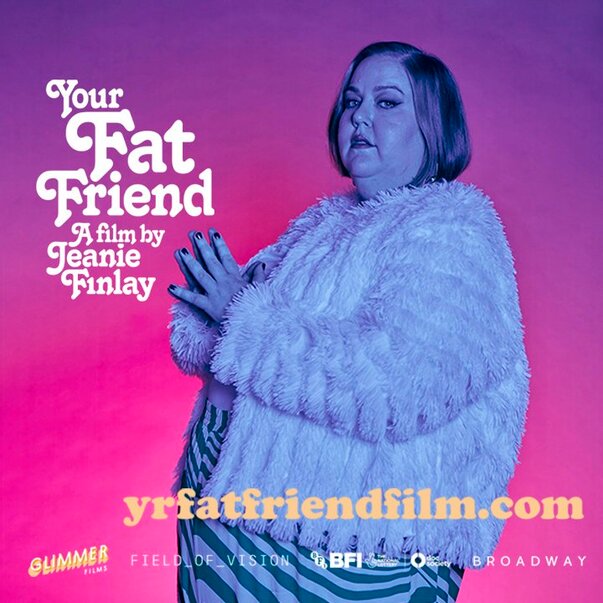

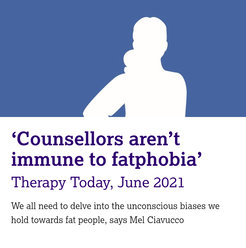

A wider understanding of ARFID in society is needed and more literature on this subject. I’m pleased ARFID is the theme for Eating Disorders Awareness Week this year, and I hope we can keep the conversation going. If you have any helpful resources or training for professionals, do let me know. NEDDE are running an ARFID course for practitioners in April, more details here. To find out more about my counselling practice, click here. Both First Steps and BEAT offer support services for ARFID. Just also a big shout out to Dr Chuks and Bailey Spinn who recently wrote a fantastic book called “Eating Disorders Don’t Discriminate: Stories of Illness, Hope and Recovery from Diverse Voices” – check it out! I recently saw “Your Fat Friend”, a documentary about Aubrey Gordon made by Jeanie Finlay. I’m a big fan of Aubrey’s work, her books, blogs and podcast - Maintenance Phase, and she’s been a huge influence on me both personally and professionally. I am a counsellor and trainer working with people struggling with eating, body image and the impact of weight stigma. I’m passionate about highlighting the importance of helping those in larger bodies with eating disorders, and training other counsellors in understanding disordered eating and weight stigma, and this film just lit even more of a fire in me. In the film, Aubrey talks about having an eating disorder and the barriers for fat people trying to access help, she says eating disorder treatment/support for fat people literally doesn’t exist. This broke my heart to hear, even though I’ve heard so many stories like this from people who have been judged, dismissed and turned away. I’ve worked for eating disorder charities in different roles for over 7 years now and it’s always disheartening to hear stories of being turned away from NHS services for not being “thin enough” and the assumptions made about fat people. As Aubrey says in the film, if a fat person has an eating disorder it is assumed that must be binge eating. This is absolutely not the case; people in smaller bodies can struggle with binge eating, and fat people can struggle with restrictive eating. Binge eating can often include restriction anyway (eating less than your body requires), it’s part of what keeps the cycle going – restrict, binge, feel guilty/ashamed, and double-down on restriction again. It’s called a binge cycle and can also be applied to dieting – diet, “fail” at the diet, shame, back to dieting. This is how diet companies make money (sometimes now not using the word diet, but “wellness” or some other fluff), because it’s never the diet’s fault, right? It’s ours for lacking willpower, being lazy/not good enough etc. This is why dieting does not “work”, it’s just creating more shame, more anxiety, more self-blame, and ultimately creating more eating disorders. Aubrey also mentions Atypical Anorexia, basically just the same as anorexia but not fitting the low BMI threshold to tick the box of being “sick enough”. This is extremely harmful as it’s stopping so many people from accessing services (though in the UK this is likely largely due to significant underfunding of ED services), and means we have no hope of “early interventions” which the NICE Guidelines state are so important for eating disorders. Being turned away for help, or anticipating not being able to get help, can often just exacerbate the disordered eating, with people feeling there is nowhere to turn. This was very much the sense I got from Aubrey talking about having nowhere to go as a fat person with an eating disorder. It’s so hard to have trust in professionals when they have all grown up in the same fatphobic, diet culture, and have little to no training in this. When I was training to become a counsellor I realised this was very much the case for our industry too – nobody talks about eating, body image, weight stigma or fatphobia, yet it is extremely likely all counsellors will encounter people affected by these issues at some point. This is why I am so passionate about this work and filling this gap – we must make it safer for fat people to access therapy. Counsellors must know about eating and body issues through an intersectional lens, looking at power, privilege, class and biases. Sadly, in my experience, this is not happening anywhere near enough as the industry is prominently white and middle class, and this is even more so in the eating disorder world. A huge amount of research into eating disorders, and treatment centres and charities, are run by thin, white, middle-class women, focussing on helping thin, white, female clients. There are so many people left out of eating disorder treatment, not only fat people but black people, disabled people, trans and non-binary people, and many more minoritized people. Treatment and therapy isn’t safe enough for so many people. This has to change. In all honesty, the difficulty I find in writing about all these issues is that I don’t want to scare people or put them off trying to find help and support. I want to raise awareness of what’s going wrong so we can work on changing it, but for individuals seeking help, I don’t want this to be another thing that reinforces the idea that there is no help for them. There is help, there are people doing great work out there, and I believe it is possible for fat people to access the help they deserve. As Aubrey says in the film, “you can’t self-love your way out of oppression” which I totally get, but you deserve help to be able to cope, as a bare minimum. There are ways to start healing. It may always be hard navigating the world as fat person but there are ways to build resilience and compassion for yourself, and help create a better relationship with food, if that’s what you would like. I’m holding in mind that people reading this may be either looking support for themselves (or individuals who are just interested) or some may be counsellors/therapists or professionals looking for what they can do. So I’ll suggest some ways counsellors/therapists/ED services can help, and if you are looking for support you can perhaps use these as green flags (good things) to look out for!

I am proud to work with people in larger bodies (and all kinds of bodies) who are struggling with a range of eating problems and body distress. Sometimes I feel like I’m the only person in their life who doesn’t tell them they need to lose weight or make them feel like their body is not good enough. We need more counsellors, therapists and people working in the eating disorder field to help fat people feel that they are safe, welcome, and cared for. I’m keen to hear other ways we can help fat people access help safely as I know there’s way more needed than just the tiny list above. We need to share ideas, so please let me know! Thanks for reading. If you’re interested in having counselling please head to my counselling page for more info. If you’re interested in my workshops and trainings, I’ll be offering more soon so check out my workshops page and sign up to my mailing list and I’ll let you know when more dates come up. Thanks! Your Fat Friend trailer: Everything Now: what does it get right about eating disorders and where does it fall short?11/19/2023 Spoilers! Everything Now is a coming-of-age drama comedy on Netflix, with a protagonist in eating disorder recovery. If you haven’t seen it, maybe go and watch it and come back, or if you’re not fussed about spoilers or have no intention of watching it and want to keep reading, then crack on! I’m a counsellor and I work with people with eating disorders, disordered eating and body image problems. I’ve worked for eating disorder charities for over 7 years now, but this does not make me an expert, these are just my opinions on the show and how they dealt with the topic. Firstly, Everything Now passed the basic bare minimum test… not showing triggering eating disorder images/scenes. When they included some ED behaviours, they were off camera and they included a warning before the episode (and they included help resources after each episode too). This already makes this show better than most other things about eating disorders, but the bar was pretty low. BEAT have some media guidelines which should be utilised by any media outlet, filmmaker or creator, but sadly this has not always been the case, as we see with shock-factor eating disorder tabloid articles, and in films such as To the Bone, which shows specific eating disorder behaviours and images of very thin bodies. Everything Now not only avoided this, they didn’t portray the protagonist, Mia, as being someone who just wants to be skinny to copy influencers on social media. This lack of emphasis on body image and vanity is refreshing, and the show demonstrates throughout that eating disorders are so much more than just negative body image or a diet gone too far. I also loved the casual queerness, by that I mean they never had to explain anyone’s sexuality, and didn’t assume heteronormativity. The show really portrayed the push-pull of recovery well, by this I mean to need to be recovered and “better” ASAP, whilst also struggling to let the eating disorder (which provides a sense of safety) go. Everything Now goes slightly against the usual trope of the thin white girl with anorexia, telling a lesser-seen narrative of a queer mixed-race woman. This was very much needed, however it still focuses on thin, rich, privileged families and barely mentions the impact of race, class and culture, an important missed opportunity in my view. This may have been something to do with it being written by Ripley Parker, who has two famous parents. It's as if they tried to make the characters less middle-class, perhaps to make it more accessible for an American audience (perhaps aiming for Sex Education vibes). This was jarring for me when seeing their homes and realising how wealthy they all were, and it’s as if they tried to ignore this or presented those kinds of homes as “normal”. In one part, the parents refer to how much they spent on Mia’s recovery. This sadly does position the story from the usual middle-class privileged lens, focussing on a thin person with anorexia who can afford a high standard of care. I’d love to see a gritty drama about a working-class person in a larger body with an eating disorder but that’d just involve them on a waiting list for months/years while their GP gives them a leaflet on “healthy eating”. Maybe not so entertaining. Sadly, I’ve heard many stories of this happening. Eating disorder treatment is predominantly for thin privileged people – these are the people who are researched, and who “gold standard” treatments are made for. It maintains the cycle of ED treatment for thin, middle-class people, created by thin middle-class people. I’ve heard many tales of people being told “we won’t let you get fat” and exercises that attempt to prove to the person that they’re not fat so they’re okay, such as the body tracing exercise in the show (which is inherently fatphobic, risky, and potentially so harmful and therefore unethical). In my personal experience, I’ve felt that conversations about fatphobia, race and class are not welcomed in the eating disorder world. There seems to be a complete silence around the very apparent weight stigma and reinforcement of fatphobia in treatment, which makes absolutely no sense considering that fear of fatness is part of many eating disorders. It’s a barrier for so many people needing help, the majority of which are not underweight. Anorexia is one of the less prevalent eating disorders, though it does have the highest mortality rate. In reality, many people with eating disorders are in larger bodies. Due to assumptions, weight stigma and fatphobia, so many people in larger bodies are not getting the help they deserve or worse, are told to lose weight, which will only make the disordered eating worse. One of the most interesting aspects of the show for me was relationships (but I would say that of course, I’m a counsellor!) The nuance of the parents’ characters, her relationship with her brother (shame it was only in one episode) and the friendship group were interesting. The parents were portrayed as trying their best, attentive and loving at times but not perfect. There’s no such thing as perfect parenting, it’s just “good enough”. In attachment theory, having a good enough parent means that as a baby you can form good enough attachment bonds, which are like templates for future relationships. Although eating disorders can be associated with trauma, this doesn’t necessarily mean a traumatic event or any major abuse or neglect. Instead, it may be to do with attachment and bonding in the early years, and how this impacts brain development, relationship with food and relationships with others. Eating disorders can often be tied into relationship wounds like this, and I might speculate in Everything Now that the mother-daughter relationship is an integral part. I would have liked to have known more about Mia’s childhood and seen more of her early relationship with her mother, but that’s just me itching for more therapeutic fodder! I got excited when they had the family therapy session and thought the defensiveness and awkwardness all around was well done and realistic. Family therapy is often part of treatment for young people with eating disorders due to the amount it impacts the whole family, but is difficult, uncomfortable and challenging for many. It’s important for parents and siblings to be involved as the relationships are so deeply affected, portrayed well with Mia and her brother, I only wish this had been woven throughout the series as it was jarring for just one episode. I particularly liked the part in the family therapy scene where the mum talks about young girls and TikTok and the others roll their eyes. This was a great way of busting the "social media creates eating disorders" myth but also showing the defensiveness that can come up for parents. This is certainly not a criticism of parents, when I say defensiveness I refer to the very understandable responses to feeling difficult emotions, which is understandable given their child has an eating disorder. Many parents can feel blamed, shamed, guilty, responsible for not being able to help their child, or even for being the reason their child has an eating disorder. There is never one reason why someone develops an eating disorder (there are biological, societal and psychological influences) so it can never be solely a parent’s fault. We do all live in a weight-biased diet culture though, so it may be that some parents benefit from reflecting on their role in the situation, and maybe even consider their own relationship with food, views about larger bodies and any food rules in the home. Even if this is not the case, the relationship in the family will need to heal and trust needs to be rebuilt. It’s tough for everyone involved and I think this was depicted well in Everything Now. There was a focus on the impact on family and friends, and how they were trying to protect Mia by keeping things from her. This of course was to avoid hurting her, though backfired as Mia just lost more trust and felt isolated as they’d lied. I’ve seen people on social media saying Mia isn’t a very nice person… not that I agree with this, but it’s difficult to be a nice person when you’re suffering, isn’t it? The idea that people with mental health problems or who have been traumatised should be quietly crying and be nice is just not realistic. Traumatised people often don’t act in nice ways, it’s why some of the most traumatised people in the world are in prison. Empathy often only seems to extend to people who are suffering in a nice, polite, socially acceptable way, but this keeps us as a society in a trap of ostracising and shaming the most hurt and marginalised people. Mia apologising at the end to her friends left me conflicted; why should she have to apologise for being the one suffering? I wondered what message that gave to the audience, for people supporting others with eating disorders, but also anyone in recovery themselves. This could potentially reinforce the shame of “look at how you hurt people”, which is not exactly a motivator for recovery. Eating disorders are shrouded in stigma and shame, and “feeling ashamed of being ashamed” as Mia’s voiceover so eloquently highlighted. Just also a quick note about Cam and the one episode where he seemed to be quite preoccupied with his body and muscles. This was jarring and strange in one episode only and seemed like a missed opportunity to explore muscle dysmorphia. Not “naming” this in the show could almost normalise it, so it’s a shame it wasn’t woven through the series. It may also have been confusing to people that Mia has anorexia but is heard vomiting (purging), as this may be confused with bulimia. There is a purging subtype of anorexia, so this likely what Mia was being shown to have. Overall, although this was a good show, there were other missed opportunities, largely around the intersection of racism, sexuality and class. In my view, eating disorders are always entangled in socio-cultural ideals and expectations, and an intersectional view is required. Eating disorders are largely tied into people's identities, so recovery means exploring the parts of the self, and building trust again in their body, and in the relationships around them. However, these conversations aren’t even happening in the real-life eating disorder world, and treatment is mostly geared towards thin white middle-class people with anorexia, so it’s a lot to ask for a TV show. Everything Now is at least a slightly new approach to eating disorder narratives, done in a respectful, responsible way, and I hope it will help lead to more nuanced conversations around eating disorders. Thanks for reading! I offer online counselling sessions, workshops and consultancy - please click to find out more. I’ve had the pleasure of facilitating some writing workshops recently, in conjunction with Arkbound, at a drop-in café in Bristol called The Wild Goose/InHope for people affected by homelessness or adversity. There were 8 weekly drop-in sessions, alternating with another facilitator each week, and we were flexible and adaptable with the content to suit attendees' needs. This meant having plenty of writing exercises up our sleeves, some of which I’d like to share with you here. It was an honour to be part of the workshops and meet some amazing people and hear some great stories. Writing can be so helpful for mental health and wellbeing - it has certainly helped me! It provides an outlet, can aid reflection, and in a group it can build connection and help feelings of isolation and loneliness. For me, performing my work to an audience at storytelling events (such as the one I co-run with my writing group - Talking Tales) helped me build confidence and feel part of a community. My experiences As somebody who has written a lot myself – journalling, short stories, novels, screenplays, blogs/articles etc - I truly believe that writing is therapeutic in all of its forms. We channel parts of ourselves into writing, whether we realise it or not. There are many things I’ve written where I was adamant it wasn’t about me, but it so obviously was! Even when writing fictional characters that weren’t like me, I was still drawing on my own emotions, which provided a powerful way of processing. I probably didn’t even realise this at the time but now as a qualified counsellor, I understand more about myself, my past and my emotions. I also recognise that I was a child who often felt unheard and like I didn’t fit in, and the process of writing something I thought might be read by others was important. This is why blogging about certain topics also became important to me. It led me to reading and learning a lot more about social inequalities, eating disorders, body acceptance, diversity etc, which a critical part of my practice. The exercises I’ll share here are ones I’ve tried personally and/or use in groups. They may not be of use or interest to everyone, so just go with whatever you’re drawn to. The most important thing about writing, in my view, is to write whatever and however you like. Do it for yourself, not to fit in what others say or to abide by rigid writing rules. Letter to your younger self A writing exercise I found helpful in the past was writing a letter to my younger self. This can be a very emotional exercise but can help build self-compassion and recognise how far you’ve come. It may help you build more understanding of things from the past, or perhaps help forgive yourself for something. When I did this exercise I started with some jokes about being “Mel from the future”. I felt awkward doing it and didn’t know how to start! But as I continued writing, I realised how much I wanted to reassure younger me that things would be okay, and that not all people treat others very nicely but that isn’t younger me’s fault. To do this exercise you might want to pick a certain age in your life that you’re writing to, perhaps that might be somewhere in the teenage years or younger. Be sure to do this at a time when you’re comfortable and calm, with some time for yourself after as it can bring up a lot. Pivotal moments We all have moments in our lives that shape us and what we’re doing. Consider writing about a “coming of age” experience in your life, or a pivotal moment in your past. Something, someone or an experience that inspired you in some way or provoked a change of some kind. It might have been a “sliding doors” moment that took your life off in a different direction. If you want to write fiction, this can be a good starting point for a “what if?” For example, what if you didn’t move away, take that job, go on a date with that person etc. Try not to dwell on any regrets here, but instead think about what can be learnt and reflected on. Arguably there are no mistakes, just opportunities for growth. A pivotal moment can often make for an opportunity for reflection years later, to recongise how far you’ve come, to see how you’ve changed and if you feel differently about it now. Burn your critical thoughts Write down your critical thoughts, the narrative that says you “should” do this, that you’re too stupid/ugly etc, that you’re useless and nobody likes you. Try writing those out on strips of paper, then either burn them and watch them dissolve, or (a potentially safer option) rip them into tiny pieces. Alternatively, you can write the thoughts down and then write an alternative thought instead. Respond to yourself the way a positive family member or friend. The unsent letter Feeling angry or upset with someone? Got something to say to someone but never had chance to say it? Writing a letter to someone, completely letting rip, and then not sending it, can be a really cathartic way of getting your anger and emotions out. It might be that you’re a bit frustrated with your boss so you might want to type out an email of what you would say – BUT DON’T put your boss's email in the address bar in case you actually send it – eek! Or you may want to write a physical letter to someone who has hurt you. This can then be kept if you wish, or ripped up or burnt if you feel that may be helpful as a “letting go” process. This exercise can also be used when a friend or relative has passed away, for when you wish you could have said something to them, or need to say goodbye. 15-minutes of writing, and re-writing, and re-writing! The idea with this exercise is that you start with something that’s bothering you, or a problem you’d like to figure out, and with each re-write you might find a bit more clarity. When I’ve done this in the past, I’ve found it gets shorter each time, and I found that the problem didn’t seem that much of a big deal by the end.

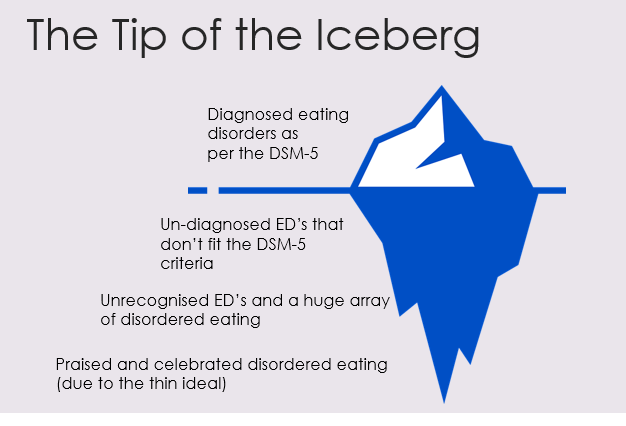

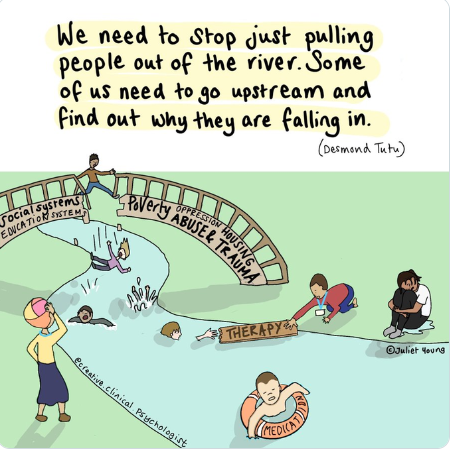

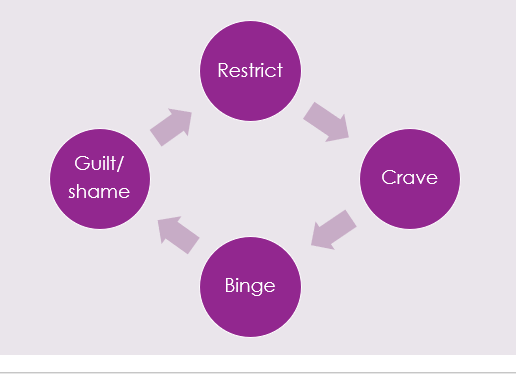

Journalling There are lots of ways to journal so don’t worry if you get a bit nervous at the sight of a blank page. You’re not writing it for anyone else (but if it helps to picture someone to write for then go for it!) I fancied myself as a bit of a Bridget Jones when I started journalling, many years ago, and used to write like I was trying to entertain an audience. It gradually became more emotional and honest over the years as I got into it. I don’t write very often now, usually when I need to get something out or process something. I also write when I’m travelling – I have books full of journalling from when I was travelling, though many of the parts from South East Asia and India mainly just involve me going on about my bowel movements! Find your own way of journalling, be that notes, bullet points, with doodles etc. Even if you don’t know where to start, you can literally start with “I don’t know what to write and this is feeling kind of awkward and silly…”. You might be surprised where it goes from there. But if it doesn’t then, that’s okay too, just be kind to yourself maybe try another time. Life writing and memoirs Writing about childhood can be helpful for many people, and writing about family and experiences. It can be a lovely way of leaving a legacy, even if it’s only for a few family members to read. If you ever think “my life is too boring to write about” then just notice that as a critical voice and be assured that everyone has a life that’s worth writing about, you don’t have to have been to exciting places or broken a world record. Everyone has the ups and downs, and the relationships and the relationship breakdowns – this is the human part which people want to hear about. Just be aware that a lot of things can come out when writing about traumatic things in the past. Because writing something down is sometimes easier than saying it out loud, there might be some things you buried deep and this might unearth them. This may be helpful, or it can re-traumatise potentially. It can be a good idea to do this whilst having counselling sessions if this is the case so that you can process these feelings safely. A final note When I started writing, I spent a long time trying to make it perfect for others to read. This was something I did in other aspects of life too, not just when writing. The perfectionist critical voice would start jabbering on, “this is rubbish, nobody wants to read this!” I couldn’t make that go away, that was deep-rooted from childhood, but I gradually listened to it less and less. Noticing it, naming it as a critical thought and knowing that I didn’t need to listen to it helped. If you’re writing to try and get published, don’t worry about trying to make it perfect and tidy until much later on, this kind of focus will only distract you in the early stages when openness, creativity and flow are more important. You don’t have to use big clever words, or have perfect grammar or spelling (luckily there are things like Grammarly which can help you with that), so just tell your truth. Even now writing this, I know it won’t be perfect, but I don’t care. If you’ve made it this far I hope you’ve found this helpful. So now, as I help others in writing workshops, I very much remember that I am not an expert, I am not perfect, but “good enough”…and so are you! Happy writing! What do domestic abuse and disordered eating have in common? How do they intersect and interplay? In this blog post, both my working worlds come together in a discussion and reflection on similarities and intersections I see between disordered eating and domestic abuse, for both victim/survivors and perpetrators. A note on language: I use the term “victim/survivors” as different people prefer different terms. I may speak about perpetrators as male, though I’m aware other genders can be perpetrators too, but I predominantly work with men. I also am speaking in binary terms in this post, but would like to highlight how trans and non-binary people are particularly vulnerable to abuse and disordered eating.  Photo by Sydney Sims on Unsplash Disordered eating Let’s start with what disordered eating actually means… well, different people define it in different ways, but for me, I like to use it as an inclusive term for eating disorders and any distress around food or exercise, irrelevant of diagnosis. Sadly, many people find it difficult to get a diagnosis of an eating disorder, and many struggle to access any help due to cultural or societal barriers. I’ve heard the “not thin enough” rhetoric too many times now from people who have been turned away from NHS treatment. BMI (body mass index) is often still used to gatekeep services, even though the NICE guidelines say otherwise, but NHS services are overstretched as it is. Despite what many people think, most people with disordered eating are at higher weights (Duncan et al. 2017) A study by Hay et. al. (2017) showed that anorexia nervosa was only 8% of all eating disorder cases, which may come as a surprise to many. The most prevalent is "other specified feeding or eating disorder" (OSFED), because unsurprisingly, eating disorders do not fit the tick boxes easily, and most people are not thin. The stereotype of the thin white teenage girl with anorexia is overused, however, access to treatment requires a level of privilege, so treatment and research is often based on this limited demographic. I created this image, which I use in my workshops, to show how I view disordered eating and how diagnosed eating disorders are just the tip of the iceberg. Eating disorder treatment can largely be focussed on anorexia nervosa because it does have the highest mortality rate, and people are often very unwell by the time they access NHS treatment. The idea of being “not thin enough” for treatment means that people are losing even more weight, exacerbating the eating disorder. The system is very much “firefighting” we might say, with people only getting the help they need when they are at crisis point. I liken this to domestic abuse services… there for when people are in crisis and are trying to flee an abusive relationship. For eating disorder recovery, the goal is often a “healthy” weight on the BMI chart, in domestic abuse it’s often to get out of the relationship. Neither of these solutions fully help the issues, it’s just dragging people out of the situation that they will enviably end up back in again because the deeper-rooted patterns and issues are not being addressed. My view of both takes a “zoomed out” approach, considering the bigger picture of societal and cultural issues we need to tackle to help prevention. Both disordered eating and domestic abuse sit within a context of patriarchal rules and gender expectations, systems of oppression around race, body ability and size, gender, sexuality etc. Poverty and food insecurity plays a huge role in relationships with food and is a contributing factor to disordered eating. Striving for weight loss is often at the root of why disordered eating develops in the first place (though not for everyone), because of our social and cultural reliance on thinking that thinner is better. There are many different influencing factors, which is why eating disorders are so complex and need to be viewed through an intersectional lens. Domestic abuse I work with perpetrators of abuse, which is my way of trying to go upstream. Helping people leave abusive relationships is so important of course, but we need to go to the root of the problem, which in many cases… is men (#notallmen etc etc). YES, I KNOW OTHER PEOPLE CAN BE PERPETRATORS, but my work is mainly with men because they are more likely to be perpetrators of abuse. I’ve written another blog about my work with perpetrators, which you can read here. I am not here to blame or point fingers at men but rather help the ones that want to be helped. Not all of them want to be helped of course, but many do want help to manage their anger and change their behaviours. This is how we break the cycle, so people don’t end up in other abusive relationships, and so that kids don’t grow up to normalise abuse. Victim/survivors and children are always at the heart of perpetrator work. What do both domestic abuse and disordered eating have in common? Control. Disordered eating and body image problems can be a form of coping, to try and regain control when other aspects of life feel out of control, or when things from the past have created a need to feel safe. Domestic abuse is about control, a fear of feeling out of control and sometimes a deep fear of abandonment. Many victim/survivors, and perpetrators, have experienced trauma or difficulties in childhood, which can contribute to needing to feel in control to feel safe. For male perpetrators, masculinity expectations in our society (e.g. strength and dominance) and the impact of living in a patriarchal society, and power and privilege, can all contribute to an abusive relationship. Domestic abuse takes many forms, coercive control being a more subtle, manipulative way of controlling and silencing victims. A person’s body and appearance can be a target for a perpetrator who may want to isolate their partner. They may make subtle comments about what they’re wearing or about their weight to fuel the victim’s body image concerns, which in turn can discourage them from going out. For a victim/survivor of domestic abuse, weight and appearance might be one thing that they feel they can control. They may need to be fixated on weight loss to meet a standard their partner expects, or it may be to avoid weight-shaming comments from them. They may experience this like gaslighting, it’s their own fault they’re fat (which they may feel means “unlovable”). They may be judged for what they eat by partners, or if money is tight they may be made to feel guilty about eating. They may prioritise feeding their kids, they may have to rely on food banks and feel ashamed. Kids can sometimes refuse food as it’s their only way to communicate that something is wrong when they don’t have the language that adults do. These are just some examples, there are many ways that food and appearance can intersect with domestic abuse, both as a coping mechanism for victim/survivors, and as a method of control used by perpetrators. Exercise and steroid abuse Although men obviously do struggle with eating disorders too, men may find themselves leaning to exercise and “bulking up”, which we could speculate as being a quest to feel more masculine perhaps or a way to feel stronger and in control when they feel emotional and vulnerable. “Muscle dysmorphia” can lead to over-exercising and the use of diet/protein products to build muscle, and there is a risk of steroid misuse. Anabolic steroids are legal for personal use, but it is illegal to supply or sell them, though this does not stop people from buying them online or through gym contacts. This is particularly dangerous as there could be anything in them. Anabolic steroids can increase anger, anxiety, aggression and hostility (Oberlander and Henderson 2012) as well as having physical effects and the risk of becoming psychologically dependent. There is a documentary by Reggie Yates on YouTube called “Fatal Fitness: dying for a six pack” which highlights many of the issues with exercise and steroids affecting men. The eating disorder voice Many people in recovery from an eating disorder speak of the “anorexic voice” or “eating disorder voice” - the critical thoughts that shame them and tell them what to eat/what not to eat. This voice, many say, is like an abusive partner (or parent) in their heads. That part can’t just be switched off, they can’t escape it, because it’s deep-rooted… it’s similar to how a victim can’t easily leave a perpetrator. The cycle of abuse is decidedly similar to a binge and restrict cycle: Shame plays a big part in this. With perpetrators we talk about the “pit of shame” and how hard it can be to get out. They can feel ashamed of their behaviour but sometimes unable to break the cycle, falling back again, feeling out of control when they get angry. For victims, trying to leave isn't just about building resilience and strength, it’s literally about safety, as the risks can skyrocket when they separate. The risk of stalking harassment and even homicide increases after separation. In the same way that victims stay in relationships to try and keep themselves safe, people hold on to disordered eating for that same safety. There is a great story/metaphor by Dr Anita Johnston about clinging to a log in a fast-flowing river. Even when you reach calmer water, and there are people on the river bank who can help you get out, the log saved your life so it’s hard to let go (the video is at the end of this blog if you’d like to watch it in full). This is meant to demonstrate the power of disordered eating, but can equally demonstrate the difficulty of leaving an abusive relationship. Both domestic abuse and disordered eating are about power and control ultimately. Both are linked to trauma, and cannot be separated from systemic issues and inequalities. However, it’s important to work in a case-by-case, client-centred way, honouring their unique experience and intersecting aspects of identity. If you’re struggling with any of the issues discussed in this blog, I offer counselling sessions online – find out more here. If you’re looking for more information and training on disordered eating, I’m offering a workshop through Online Events on 27th September. I also plan to run training elaborating on this blog, on domestic abuse and disordered eating, so if you want to be updated on this please sign up to my mailing list. Resources